the coffee art of

SAUL BOLAÑOS

by

JOHN M. EDWARDS

___________________________________________

John

Edward's work has appeared in Amazon.com, CNN Traveller,

Missouri Review, Salon.com, Grand Tour, Michigan Quarterly

Review, Escape, Global Travel Review, Condé Nast Traveler,

International Living, Emerging Markets and Entertainment

Weekly. He helped write “Plush” (the opening

chords), voted The Best Song of the 20th Century by Rolling

Stone Magazine.

John

Edward's work has appeared in Amazon.com, CNN Traveller,

Missouri Review, Salon.com, Grand Tour, Michigan Quarterly

Review, Escape, Global Travel Review, Condé Nast Traveler,

International Living, Emerging Markets and Entertainment

Weekly. He helped write “Plush” (the opening

chords), voted The Best Song of the 20th Century by Rolling

Stone Magazine.

A

MODERN DAY ALCHEMIST

Costa

Rica, a coffee democracy in a sea of banana republics, is

known more for its number-one export than its art. It’s

only natural then that the Costa Rican photographic artist

Saul Bolaños decided to fuse the two and extract art

from the ubiquitous bean. His patented cafegrafia ™

(coffee graphics), photo images made real by coffee, explore

the offbeat flight paths of Central American visual art.

Bolaños’s

process is quite revolutionary for a nonrevolutionary republic.

Using both powdered and liquid coffee as a pigment to make

up a photo image -- instead of the standard silver emulsion

-- he has at the same time developed a special secret chemical

process to make the images absolutely permanent.

No darkroom is needed. Developing an image can be accomplished

in full sunlight. Having previously treated a surface of a

variety of media (paper, glass, wood, ceramic, and stone)

for imaging, Bolaños simply strokes it with coffee,

using a brush, and presto! The subject magically appears.

Bolaños’s

process is quite revolutionary for a nonrevolutionary republic.

Using both powdered and liquid coffee as a pigment to make

up a photo image -- instead of the standard silver emulsion

-- he has at the same time developed a special secret chemical

process to make the images absolutely permanent.

No darkroom is needed. Developing an image can be accomplished

in full sunlight. Having previously treated a surface of a

variety of media (paper, glass, wood, ceramic, and stone)

for imaging, Bolaños simply strokes it with coffee,

using a brush, and presto! The subject magically appears.

In front of the Hotel Gran Costa Rica in the capital San Jose’s

19th-century Plaza de la Cultura -- a bustling marketplace

of manic vendors hawking everything from psychedelic Guatemalan

textiles to Costa Rican T-shirts -- the middle-aged Bolaños

sometimes sells inexpensive cafegrafia to passing tourists.

“To be an artist in Costa Rica is not easy,” says

Bolaños, a self-professed caffeine addict, with a lava-hot

cup of java steaming in one hand. “There are many art

lovers but very few art buyers.”

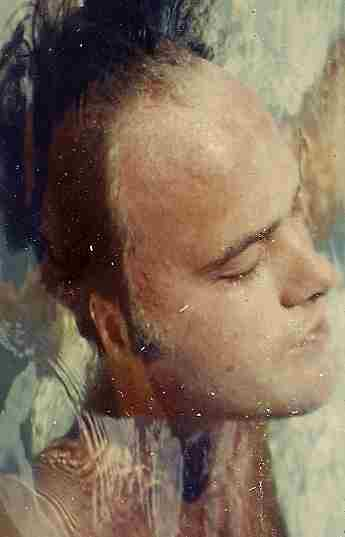

He

displays what looks like an old photo of a Marquezian nude,

then rubs it, holding up a finger lightly dusted with coffee

grinds. “My favorite is Costa Rican espresso, dark roast,”

he says, by way of explanation, to an amazed onlooker. “I

drink five cups a day. I stop a few weeks each year when it

affects my nerves.”

To Bolaños, the photochemist, Costa Rica is coffee,

and from his laboratory lair in the suburb of Ezcasu, he has

discovered, in the last two decades or so, many things to

do with it besides drink it. The staining properties of coffee

are well known (Bolaños taps his teeth to demonstrate);

the reaction of coffee with certain metallic oxides is not.

“In

1989, I discovered a strange reaction. I made a photo image,

which, after being covered with coffee extracts, reacted outside

of a darkroom -- and the coffee took the place of the image.

The quantity of coffee ‘fixed’ by the image was

in direct proportion to the amount of oxide in the image,

thus giving a perfect gradation of opacities (middle tones)

made up of coffee.” After many years of direct exposure

to sunlight, test images show no evidence of fading, difficult

to achieve even with conventional photo chemicals.

We

might conclude Bolaños is some kind of alchemist since

he reveals little about he achieves his beautiful golden effect.

“The tones are richer and warmer than any process I

know of, and I know many,” he boasts about his roasts.

We

might conclude Bolaños is some kind of alchemist since

he reveals little about he achieves his beautiful golden effect.

“The tones are richer and warmer than any process I

know of, and I know many,” he boasts about his roasts.

In fact, Bolaños’s magical mystery tour into

the surreal world of coffee art is the result of a lifetime

of research. Born in San Jose, Bolaños spent his boyhood

buzzing around photo studios, surrounded by cameras, lenses

and prints. In 1970, he moved to America and began his professional

career as a photojournalist with a California newspaper. In

1973, he switched to commercial portrait and advertising photography,

while teaching his art on the side and perfecting his craft.

His obsession with the photochemical process then led him

to Europe, where for eight years he haunted laboratories in

Switzerland, France, Germany, England and Italy, pouring like

a nosey Nostradamus over technical literature. A return to

his homeland brought all the ingredients together, and in

1989 he embarked on his research with coffee photography.

Since

then he has developed five different processes using coffee,

in addition to decaf techniques using other substances like

gold, bronze and quartz. Besides creating and developing a

new medium, the restless innovative wizard Bolaños

has focused his efforts on inventing new technologies, including

a special camera and enlarger. His Faustian laboratory lair

in Ezcasu has the air of a mecca of science as well as a café

of aesthetics, including a library that would make any Merlin

envious and equipment he has either built or modified himself.

Since

then he has developed five different processes using coffee,

in addition to decaf techniques using other substances like

gold, bronze and quartz. Besides creating and developing a

new medium, the restless innovative wizard Bolaños

has focused his efforts on inventing new technologies, including

a special camera and enlarger. His Faustian laboratory lair

in Ezcasu has the air of a mecca of science as well as a café

of aesthetics, including a library that would make any Merlin

envious and equipment he has either built or modified himself.

“If

I lost everything, I’d start all over.” Bolaños

bruits. “Your average photochemist is a flunky for the

company he serves, whereas historically the alchemist was

adept at many crafts. After all, leaving behind a lasting

impression is the next best thing to eternal life.”

So well-versed is he in the technical science of photography

that his discourse often bewilders the amateur shutterbug

and cappuccino quaffer. “After cafegrafia, I developed

orografia, using powdered gold as a pigment. I dissolve gold

in agua regia (nitric and hydrochloric acids), and the resulting

gold chloride is made into a fine metallic powder by adding

ferric salt to the solution. The powdered gold is dried and

used to dust and develop photo images that will accept it.

The images are fixed by gun-spraying them with a varnish.”

Gold images on red crystals were exhibited by Bolanos in the

Costa Rican Museum of Art in 1990.

Bolaños’s newest art is vitrografia, related

to high-temperature chemistry and the properties of quartz.

“In this process, a glazed ceramic piece is covered

with a light-sensitive emulsion and exposed to light by contact

under a positive or a negative. The image is then developed”

--  Bolaños

curls his fingers into Spanish question marks and rolls his

eyes comically like a mad scientist -- “with powdered

quartz and a metallic oxide. The image is then fired in a

chamber until the quartz fuses and ‘vitrifies’

and combines with the glaze.” According to Bolaños,

vitrografia portraits are not affected by gas, water, fire,

acids, or chemicals -- and will last for centuries in the

open air, making them ideal for cemeteries. “This is

only a small part of my research. What I have in my lab now

I cannot publish at this time,” he says with a sly smile.

“Right now it’s all just a curiosity.”

Bolaños

curls his fingers into Spanish question marks and rolls his

eyes comically like a mad scientist -- “with powdered

quartz and a metallic oxide. The image is then fired in a

chamber until the quartz fuses and ‘vitrifies’

and combines with the glaze.” According to Bolaños,

vitrografia portraits are not affected by gas, water, fire,

acids, or chemicals -- and will last for centuries in the

open air, making them ideal for cemeteries. “This is

only a small part of my research. What I have in my lab now

I cannot publish at this time,” he says with a sly smile.

“Right now it’s all just a curiosity.”

Luis Ferrero Acosta, Costa Rica’s best-known art historian,

has called Bolaños “a master;” others say

he is a “witch,” an accusation which he does not

deny.

Since 1990, his work has been the focus of numerous gallery

exhibitions, newspaper and magazine articles, and TV spots

in Latin America. But in the U.S. and abroad his work is still

relatively unknown. Two techniques were featured at the 1993

Photo & Image Expo (Seattle) and the 1993 USA Coffee Show

(Boston). But the international art community (perhaps the

world’s leading coffee consumer) is beginning to wake

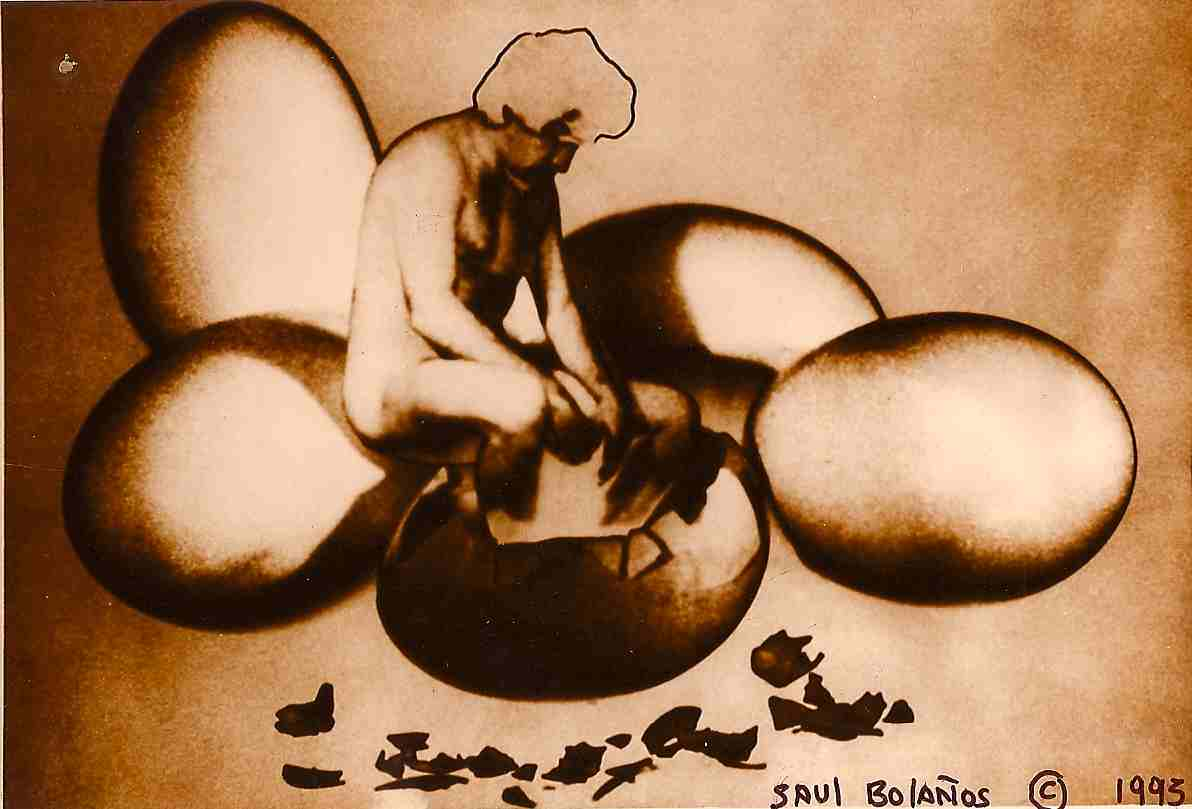

up and smell the coffee. At the prestigious 1993 International

Exhibition of Photography (Puyallup, Washington), for example,

Bolaños won medals for two works: “The New Man”

and “The Dreamer” -- the first time Costa Rica

had won in a major international photo competition. The anonymous

entries were judged on artistic merit alone, not other ingredients;

judges remained unaware that Bolaños had maybe slipped

them a little caffeine.

About “The New Man,” a weird self-portrait of

the artist emerging from a giant egg, Bolaños says,

“In the search for myself I grow only when breaking

away from old beliefs. My body dies once but the person within

dies a few times in a lifetime and is transformed.”

Bolaños has refused countless lucrative offers to mass-reproduce

other artists’ work using his strange brew. “I

don’t want art to be like old newspapers in the trashcan.

I didn’t renew my contract with my old agent. I get

by selling my work myself. I won’t get rich this way

but money isn’t everything.” Bolaños smiles

mischievously. “But that doesn’t mean I can’t

entertain serious offers.”

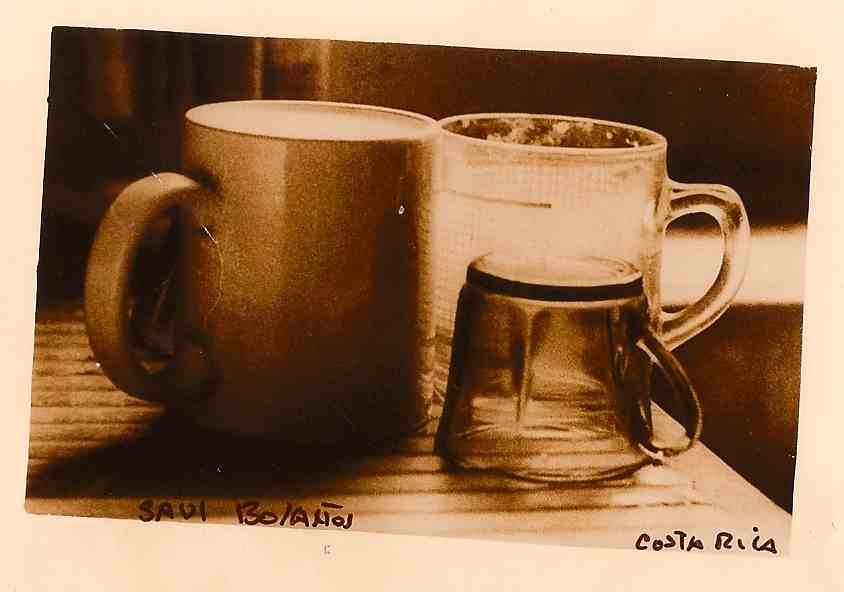

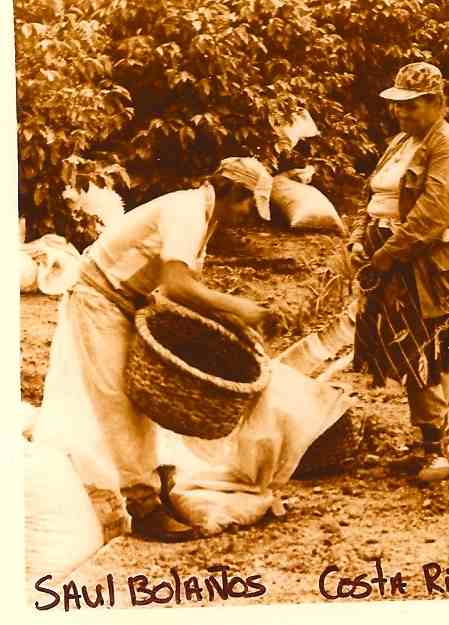

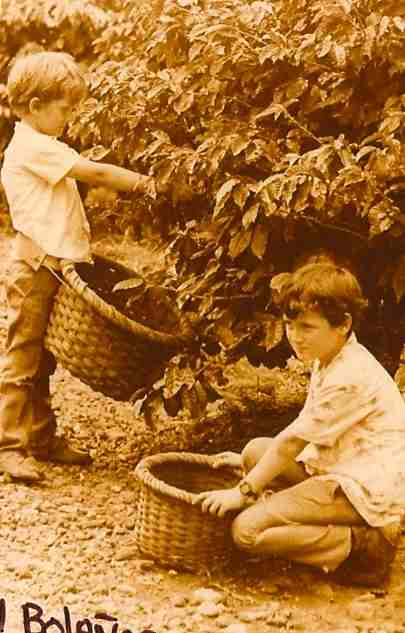

His overpowering eye instead centers on his main addiction,

be it a rural scene of children picking coffee beans or the

traditional coffee-making apparatus in still life, their sepia-like

fresh-brewed textures driving home the fact that Costa Rican

life, outside the tourist districts, hasn’t changed

much in the last century. Other shots range from tranquil

beach and rural scenes and portraits to espresso-like prints

of magical realism involving clowns with balloons and dreamlike

nudes.

Bolaños is now setting his sights and lenses on Big

Apple competitions and exhibitions. “I’ve never

been to New York, but I hear they appreciate good coffee there.”

Where better to bring his caffeinated creations to boil than

among the brave baristas of New York City’s art scene,

Starbucks excepted. “I do not drink or smoke, no religion,

no politics, no sports, no TV. I am extra-sensitive to what

I consume -- but coffee, luckily is still legal. It gets me

going: I like it pure, without fat, sugars and artificial

colorants. His response to skeptical critics: Take art not

with a grain of salt but with a little cream and sugar.