the reluctant collector

CAROL R. SCOTT

___________________

Carol

R. Scott was a freelance writer and communication consultant.

Now, in her retirement, she teaches English to adult immigrants

from Africa, Asia, Central and South America and the Middle

East.

TREASURE

IN THE ATTIC

“I’d

like to introduce you to Carol Scott. She’s a collector,”

Franklin Robinson, then President of the Rhode Island School

of Design Museum, said as he introduced me to a board member

using that designation. The occasion was a retrospective --

“Prints Between The Wars” that included 29 pastels,

paintings and drawings from the estate of American artist

Mabel Lisle Ducasse (1895-1976) of which I owned over 500.

I

had never thought of myself as a collector, although I’ve

worn many hats: free-lance writer, consultant, ad copy person,

executive and sometimes chief in charge of PR, I’m not

an artist; art simply gives me pleasure.

I

hadn’t set out to be a collector. I am neither particularly

acquisitive nor wealthy enough to afford an important collection.

But somehow, I inherited two major collections: the paintings

and drawings of Mabel Ducasse and the historic photographs

of Arthur Swoger. I never met Mabel Ducasse and only briefly

got to know, before his death, Arthur Swoger.

I

hadn’t set out to be a collector. I am neither particularly

acquisitive nor wealthy enough to afford an important collection.

But somehow, I inherited two major collections: the paintings

and drawings of Mabel Ducasse and the historic photographs

of Arthur Swoger. I never met Mabel Ducasse and only briefly

got to know, before his death, Arthur Swoger.

My

passion for art, my affinity for artists, my sense of aesthetics

and confidence in a good eye is a result of my upbringing.

I should really say more chutzpah than confidence (everyone

else said I was crazy).

My

family home featured original paintings, sculptures and beautiful

furniture such as early Eames chairs. My parents also personally

cared for artists. Ernst Lichtblau (1883-1963), a gnome of

a man at 5-feet tall, became an ongoing guest in our first

home.

Lichtblau

arrived in the US after fleeing Austria and the Germans in

the 40s and would later be remembered as founder of the Department

of Interior Architecture at the Rhode Island School of Design.

He brought both a European/Viennese and mid-century sensibility

to his design, recommended and selected fine furniture, exquisite

fabrics for sofas and cushions, proscribing their placement

according to colour, shape and style. We lived with built-in

shelves and drawers inspired by geometrical art of Mondrian

with flat matte-like squares of colour, cork floors, an abundance

of wood, chrome ,paintings and prints by local artists. An

appreciation for art became second nature.

And at the age of 20, when I left my husband, with babe in

arms, a crib, a minimum wage job at a local art gallery, and

a “ family” of artist friends, I knew that furnitureless

as I was, my first apartment adornments would be paintings

and drawings .

I

started collecting paintings and sculpture some 50 years ago.

My first purchase, by an artist/sculptor who would later become

my lover, was a beautiful drawing of entwined lovers. Priced

$75 and paid in increments of $5 a month, was a big investment

at the time but I just couldn’t resist.

Over

the years, I continued collecting – very slowly indeed.

I attended exhibitions, wrangled invitations to salons and

often posed for paintings and sculpture. I soon had a modest

collection of contemporary New England art that fit nicely

into the apartment and would grow larger as I moved into larger

spaces. Because

artists were my friends, I was often portrayed in their work.

Quick pastel portrait sketches and bas-reliefs of my face

in many forms, bronze torsos that resembled miniature versions

of wooden sculptures found on the prow of ancient ships are

only some examples. Later I added portraits of others, landscapes

and sculptures.

So

how did such a modest assemblage evolve into an overabundance

of art now spilling out of the attic and bursting closets

at their seams and leaving not an inch of wall space for the

calendar? The answer is an adventure story that includes murder,

mayhem and a rough patch of disengagement and depression.

My

thirties were marked by the deaths of friends, young and old.

One friend killed himself in anger, found hanging by his wife

after an argument. Another at 35 was done in by diabetes and

drink. Though warned, she died a year after she fell into

a coma. A cousin swerved to avoid a rabbit – was tossed

from his car – died instantly as did the rabbit. A 19-

year-old set herself on fire; no one really knows why. There

were more; twelve in all, so many who would be “un-remembered.”

The

last was Norma Rainone, a neighbour and friend, who was shot

in a robbery outside her back door. During those three sad

years before she was murdered, I ran into her occasionally.

When I did she would talk about boxes of a friend's paintings

she had stored in her attic. They would be thrown out, she

explained, could I help her mount a show or do some PR? Overwhelmed,

I said no.

After

her death, repenting my harshness, I spent days with Edward,

her lover, emptying her fridge, listening to CDs of her reading

the poetry of a university acquaintance, sending remembrances

to people she loved -- a process of mourning that felt comforting

and complete. We worked together, packing his things for his

escape to an island/country named Saba. Finally we came to

the boxes.

We

were stunned as we went through each box and discovered the

life’s work of one artist from childhood to death. There

were six boxes in all. We thought we might find a few dozen

paintings Shocked, we found 500 pastels, oils, etchings and

fine pastels carefully inserted between the pages of old,

extra-large sized Life magazines.

We

were stunned as we went through each box and discovered the

life’s work of one artist from childhood to death. There

were six boxes in all. We thought we might find a few dozen

paintings Shocked, we found 500 pastels, oils, etchings and

fine pastels carefully inserted between the pages of old,

extra-large sized Life magazines.

The

quality was staggering. Hopperesque women from the 1920s wearing

silk stockings and cloches, blowing smoke rings in the air.

A solitary woman on a bench waiting for a train perhaps --

the viewer doesn’t know. A turbaned beauty applying

makeup with pastel so thick one would swear it truly resembled

lipstick. Nature studies of flowers, cicadas, worms, butterflies

and moths magnified 100 times which all reminded us of the

work of Georgia O’Keeffe

There

were letters, articles and documents confirming that Mabel

was a graduate of the Art Student’s League and Pratt

Institute in New York and from the University of Washington.

We learned that she was the first person in the United States

to receive a Master of Fine Art.

We

found clippings that attested to her brilliance and exhaustive

knowledge of art. She had been the art critic columnist for

what was then The Providence Journal, Rhode Island’s

largest news outlet in the early 1900s.

What

is your plan, I asked Edward? Donate it to the Providence

Art Club, he said. They had shown an interest. No, I objected,

fearing the collection would be buried in this somewhat exclusive

club’s cellar. Edward agreed and passed the collection

onto me. I became re-engaged with life. Though Ducasse was

unknown to me, I knew that unlike my lost friends this would

be one person whose work and life would not be forgotten.

I

photographed the work and traveled it around. The RISD museum

(Rhode Island School of Design) booked a show two years ahead.

The Vose Gallery of Boston was impressed and encouraging,

but pastels, I learned, were not its thing because pastel

drawings are more difficult to maintain and sell. The Newport

Art Museum and Rotch Duff Jones House and Garden Museum and

several private galleries planned shows down the line.

I plunged, feet first, into researching and learned that Mabel

moved twice to Rhode Island (doomed to live in Rhode Island,

she said) as she followed first one (a philanderer) then another

husband (a philosophy professor) to the State. Brown University

-- where her husband taught and the institution to whom she

had bequeathed her possessions, said her art had no value

– accepted the house she designed, her easel, pastels

and furniture but made it clear they would not keep her art.

I plunged, feet first, into researching and learned that Mabel

moved twice to Rhode Island (doomed to live in Rhode Island,

she said) as she followed first one (a philanderer) then another

husband (a philosophy professor) to the State. Brown University

-- where her husband taught and the institution to whom she

had bequeathed her possessions, said her art had no value

– accepted the house she designed, her easel, pastels

and furniture but made it clear they would not keep her art.

It

took years of persistence to see Mabel’s art recognized

but now there are 1,700 entries when one googles her name.

Her work hangs in the homes of my friends, in several museums

and galleries across the country. Her work, so far, is surviving

the test of time.

For

the most part, the Ducasse work has been returned to Seattle

and is frequently exhibited at the Martin–Zambito Fine

Art gallery close to where she lived and went to school. There,

David Martin and Dominic Zambito, gallery owners and collectors

of collections write about her and other lesser known artists

and their historical place in northwestern regional art. But

not all of her work is there: the lipstick lady is in the

RISD museum; a portrait of her friend Anne Louise Strong can

be found at the Florida International University as part of

the Wolfsonian Collection; breathtaking still life works can

be found at the Denver Museum and in the homes of many friends

and also strangers.

I’ve

kept some of her work. One of my favourites is a WWI patriotic

rendering of a mother rocking her child next to a gold-starred

window while waiting for a soldier/husband who will never

come. Two others speak to my love of the outdoors and the

unusual: one features a spectacular oversized caterpillar

making its way across two pompom blossoms; the other an equally

large and rather monstrous worm resting on tomato plant leaf.

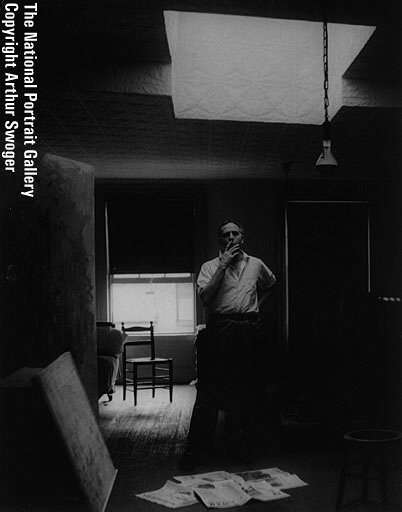

Mabel

Ducasse was not the only collection I came upon under odd

circumstance. Decades later, the photographer Arthur Swoger

and his writer wife, Rachel, were living down the hill from

my 1724 house in the small town of East Greenwich. I met them

briefly through friends before Arthur died.

He

was handsome and, most often, sweet – but ill and feeble

at that time; she was vigorous, outspoken, wryly funny and

very impatient.

In

his 80s, Arthur became cranky, demanding and ever more frequently

in and out of hospitals until a discouraged Rachel finally

arranged to put him in a home. As Arthur raged on in a senior’s

citizen home, Rachel and I connected. My dog, Mariah and her

cat brought us together as more than neighbours. It started

when my dog lunged toward her cat. The leash held, Rachel

forgave me and we became Scrabble friends.

And

that’s how I became acquainted with Arthur Swoger’s

large and magnificent photographs of animals, insects, flowers

and mushrooms, much of it commissioned by National Geographic.

The Swogers had made their home in Greenwich Village, the

heart of where the arts and artists thrived from the 40s through

the 80s. Fun-loving, bohemian people, often visiting the Cedar

Tavern (affectionately nicknamed the Bar), and known as the

“living room” by some of the greatest abstract

expressionists, writers and critics of their time, Arthur

had taken hundreds of un-posed photos of every one.

And

that’s how I became acquainted with Arthur Swoger’s

large and magnificent photographs of animals, insects, flowers

and mushrooms, much of it commissioned by National Geographic.

The Swogers had made their home in Greenwich Village, the

heart of where the arts and artists thrived from the 40s through

the 80s. Fun-loving, bohemian people, often visiting the Cedar

Tavern (affectionately nicknamed the Bar), and known as the

“living room” by some of the greatest abstract

expressionists, writers and critics of their time, Arthur

had taken hundreds of un-posed photos of every one.

Notable

subjects included Jackson Pollack, Willem and Elaine DeKooning,

Salvador Dali, Franz Kline, Philip Guston, Harold Rosenberg

and many more. Scenes ranged from a rather drunk Franz Kline

necking at the bar with an anonymous beauty, to critics arguing

philosophy (or so it seemed) and quiet dignified views of

tableside chats between the deKoonings, Frank O’Hara,

Mercedes Matter etc. Rachel shared the story of her years

of anger, all the years she supported them so that Arthur

could pursue his art. An artist herself, she had little time

to follow her heart, always held a 9-5 to pay the family keep

and was left with many painful memories she preferred to put

aside. While walking Mariah every day, I’d find boxes

of Arthur’s notebooks, photos, negatives and sketches

put out for trash. I waited a month before I told Rachel that

I had picked up every box, examined his work carefully and

was convinced I could sell it and help her get out of debt.

What

I didn’t sell of Arthur’s work stays mostly in

my closet, the negatives of mid-century artistic celebrities

in waiting. The slides of mushrooms and other nature studies

have not yet found a home. One, a close-up of coupling grasshoppers,

hangs in my home next to my first purchase - the entwined

lovers - above my bed. I'm hopeful that one day an appropriate

library, museum or other interested institution will request

a donation.

Works

by Arthur’s wife Rachel, who did not paint until she

retired, have been added to my original collection. An elegant

and colourful watercolour of hers sits over the mantel and

a nude self-portrait called Valentine hangs over a dresser.

And

of course, my walls and surfaces remain covered with art.

As I’ve aged and traveled, I’ve added small pieces

to the existing collection: a coffee root sculpture purchased

at a Costa Rican  roadside

stand; a hand-carved wooden duck given me by a Balinese wood

carver; an Ethiopian clay figures from Israel; a copy of a

watercolour of friends’ home and pond south of Paris

where I once stayed.

roadside

stand; a hand-carved wooden duck given me by a Balinese wood

carver; an Ethiopian clay figures from Israel; a copy of a

watercolour of friends’ home and pond south of Paris

where I once stayed.

It’s

the memories that give meaning to my life now. So I’ve

kept the long time favourites: two architectural photos by

my daughter Diane, the figurehead and bas-relief I once posed

for, a drawing owned by my parents, a bronze horsewoman inspired

by a friend and an oil of a single rose created by another.

And

of course, most of all, my pride and sense of accomplishment

at knowing that my efforts to save and share some wonderful

art that would otherwise have been lost have not been in vain.

My life has been enriched by all these wonders that grace

my surroundings.