Montreal

born artist Kapil Harnal (1977-) obtained his BA in Fine Arts

from Concordia University, has exhibited in Montreal at The Lawless

Gallery (1999), Galerie Schorer (1999-2001), The VA Gallery at

Concordia University (2001), La Galerie 1637 (2001). His first

solo exhibition was at Galerie Entre-Cadre (2002).

Montreal

born artist Kapil Harnal (1977-) obtained his BA in Fine Arts

from Concordia University, has exhibited in Montreal at The Lawless

Gallery (1999), Galerie Schorer (1999-2001), The VA Gallery at

Concordia University (2001), La Galerie 1637 (2001). His first

solo exhibition was at Galerie Entre-Cadre (2002).

____________________________________

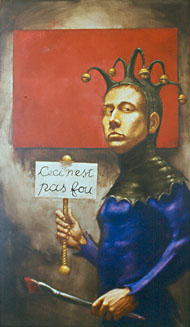

The art of Kapil

Harnal is an interesting addition to the contemporary Canadian

art context. His work evokes the baroque and classical styles

through a realist approach to drawing, colour and use of light.

He employs unique forms of representation that imbue his paintings

with modernity and freshness. And while he portrays people, he

does not make portraits. As he explains, “The individual

comes into the concept rather than the concept being about the

individual.” Harnal creates paintings that reconfigure the

traditional notion of portraiture by juxtaposing his refined technique

with unique and often humorous concepts. Through this sometimes

light and comical approach, Harnal serves notice that he does

not want to load his paintings with complex ideas. However, some

of Harnal’s paintings do in fact carry a strong message

and could be interpreted through a wide range of associations:

in some instances, the messages can be quite controversial. That

he does not view himself as a symbolist or conceptual painter

is beside the point seeing that once a work of art is out of the

hands of an artist it can be construed in an infinite number of

ways.

Harnal

is undoubtedly a talented and skilled artist who has a strong

command over colour and light. Some of his earlier works demonstrate

the eagerness and curiosity of a young painter experimenting with

different media and forms of representation. At one point, he

was interested in reproducing frozen frames from films such as

Francis Ford Coppola’s Rumblefish. To these images,

he added his own light and colour schemes in order to achieve

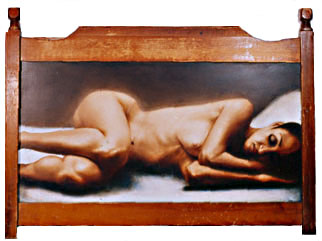

the desired effect. At around the same time, he became intrigued

by surrealist concepts, such as found objects, applied to The

Sleeper, which features a sleeping nude woman framed by the

head board of a bed to the effect that the image of a sleeping

figure is so closely tied to the idea of a bed it pre-empts the

free association characteristic of surrealism. “Duchamp

would have been rolling over in his grave over that one,”

joked Harnal.

The Sleeper

oil on wood, 34 x 18 in.

|

His most

recent work features the presence of the female figure, usually

portrayed nude or scantily dressed. This contrasts with his earlier,

classical representation of women that allowed Harnal to hone

his talent as a figurative painter. But it was only after his

peers criticized him for not pushing the envelope enough that

he began to experiment with new forms.

His current

Face Card Series reveals Harnal’s predisposition

to classical representation, yet what is new here is the painter’s

own modern and imaginative twist.

The

Face Card Series is a technically striking collection of paintings

that depicts human figures in the form of playing cards. The idea

a card could be likened to a canvas came to him in 1996 while

painting a traditional card for an art class.

In the

Queens of Hearts and Clubs, as in all other 'cards', the dual-figured

representations are not mirror images of each other, so the viewer,

to his/her pleasant surprise, uncovers movement and vital presence

in what would otherwise be a motionless and flat form of representation.

If only Harnal had pushed creative envelope even further by exploring

the symbolic and dualistic possibilities that are already implicit

in the work; instead, he sticks to his stated artistic intent:

to produce work that is light and disarming.

Queen of Hearts

oil on panel, 48 x 32 in.

|

|

Queen of Clubs

oil on panel, 48 x 32 in.

|

|

Queen of Apples and Peaches

oil on panel, 48 x 32 in.

|

|

Queen of Diamonds

oil on panel, 48 x 32 in.

|

|

Queen of Potatoes

oil on panel, 48 x 32 in.

|

If historically

cards have been used to reveal hidden meanings, in Harnal’s

series several of the pieces can be viewed at ‘face’

value. His approach is often refreshingly tongue and cheek. In

The Queen of Potato Chips, he has added his own comical

suit and in The Queen of Clubs, he indulges in a clever

play on words by painting his model dressed in a golfing shirt

and cap coupled with a golf club in hand. Other works in the series

are more serious and emotive. The expression of the woman depicted

in The Queen of Hearts suggests a lover caught off guard:

here, the work’s intimacy is achieved through the Queen’s

playful expression. However, in the Queen of Spades, a

sinister quality pervades as the bare breasted woman looks connivingly

at the viewer while fingering the blade of a spade.

Some

of Harnal’s general depictions of women follow the historical

view that designates the female as the embodiment of evil and

sin. His partially or completely nude women can be read as having

exhibitionist tendencies while the only male in the series, (The

King), is a double portrait of Harnal himself, is fully and ornately

clothed. Whether or not this double standard is intentional, the

artist bares some responsibility for the effects. To wit: the

gratuitous nudity that appears throughout the series distracts

the viewer from penetrating the deeper meanings in, for example,

The Queen of Spades which has a powerful content. So again

with all due respect to the artist’s intended unserious

subject matter, his images evoke other evident associations.

Queen of Spades

oil on panel, 48 x 32 in.

|

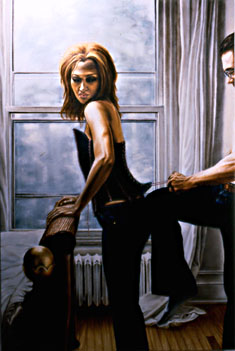

Harnal

is currently working on a series of corset images where once again

he runs the risk of authoring perhaps unintended but very problematic

associations. In Corset I, Harnal portrays himself tying

up the laces of the corset on the woman in front of him. He depicts

his body with strong movement, whereas the woman holds onto the

bed frame with a compliant expression on her face. Corsets have

been long recognized within feminist discourse as a symbol of

female oppression. The movement and expressions of the figures

in this painting could indeed reinforce these associations.

Corset I

oil on linen, 72 x 48 in.

|

Harnal

is still a young man whose evolution as an artist is a work in

progress. He should be made aware of the danger that if he continues

to portray the female as an object instead of an object of contemplation,

his work may become stereotyped as exploitive, which would be

a shame because in much of it his voice is strong. When Harnal

takes full charge of that voice, the clarity that is now only

haphazard in his painting will be the foundation upon which his

reputation as a significant artist is established.