Nick

Catalano is a TV writer/producer and Professor of Literature

and Music at Pace University. He reviews books and music for

several journals and is the author of Clifford

Brown: The Life and Art of the Legendary Jazz Trumpeter,

New

York Nights: Performing, Producing and Writing in Gotham

, A

New Yorker at Sea,, Tales

of a Hamptons Sailor and his most recent book,

Scribble

from the Apple. For Nick's reviews, visit his

website: www.nickcatalano.n

Men are

apt to mistake the strength of their feeling

for the strength

of their argument.

William Gladstone

The controversy

in Trump’s Washington, Bolsonaro’s Brazil and

Orban’s Hungary involving facts and ‘alternate’

facts, truth and lies, objective reporting, ‘fake news’

and other polarities invites inquiry into historical analogues.

In the past

few issues of Arts & Opinion I

have examined the history of political rhetoric, the process

of chronicle evolving into myth, and the sorry curricula in

schools, as players in the present drama of the search for

truth.

But in order to

view the convoluted process of the evolution of truth and

incontrovertible establishment of fact, I though it might

be helpful to trace the movement of one universally accepted

truth/fact/ law in its movement along the path of pitfalls

on its way to universal acceptance. I chose a story from Astronomy.

In the brilliant

scientific and philosophical minds of giants like Aristotle

and Ptolemy, the search for order led to their theory of a

solar system where the sun revolved around the earth. Actually,

their generalizations in astronomy, geography, math and science

were to become barometers of acute knowledge even up to the

present time. But their geocentric solar system explanation

was incorrect . . . Despite their other achievements of genius,

the work of these giants stumbled here. Incidentally, this

is often happens; scientific experimentation and theorizing

is conducted by imperfect human beings no matter their IQs.

This geocentric

or sun revolving around the earth view of the solar system

and the allied Aristotelian and Ptolemaic insistence that

the stars were ‘unmovable’ objects was totally

supported and promoted by medieval Christendom. The church

was always anxious to ally its articles of faith with the

most prestigious minds i.e. Aristotle, Plato (via St. Augustine),

and, later, philosopher/theologians Aquinas, Scotus and William

of Ockham. The church’s association with these intellectual

icons gave it a unique measure of appeal among the world’s

religions.

But in order to

maintain its thousand year dark ages dominance over the political,

social, economic as well as spiritual elements in society

Christendom (I include both the Vatican and Lutheran Protestantism)

ran the risk of clashing with scientists who might challenge

its unshakable insistence on any ‘laws’ that the

church had approved. Thus the geocentric law of the solar

system was destined to remain unchallenged even in the Renaissance,

because of the power of religion.

Except

that’s not what happened.

Except

that’s not what happened.

In 1514, Polish

astronomer, mathematician, theologian and polymath, Nicolaus

Copernicus sent out a pamphlet that stated the sun was the

center of the solar system -- not the earth. He also maintained

that the earth’s rotation accounted for the rising and

setting of the sun, and the movement of the stars and that

the cycle of the seasons was caused by the revolution of the

earth around it. The church did not immediately condemn the

book perhaps because it believed Copernicus’s theory

were so outlandish that it wouldn’t be taken seriously.

But soon a scientific fad took hold with the inexpensive costs

of telescopes and then, when Tycho Brahe (1546-1601), who

had methodically observed the skies with sophisticated instruments,

utilized the latest model to observe a moving star supernova

(SN 1572), church authorities began to squirm. How could a

star be moving when the most respected ancient astronomers

together with the pronouncements of the church had long held

that stars were fixed objects?

The supernova

(SN 1572) challenged the fixity of the heavens. In addition,

Brahe showed that unassisted sensory perception, relied upon

since Aristotle’s time for the building of knowledge,

could be misleading: the discovery of truth required evidence,

and evidence was to be obtained through new well-calibrated

instruments.

Then two months

before he died in 1543, Copernicus published his full book,

On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, which

caused further uneasy stirring in the Vatican.

Next,

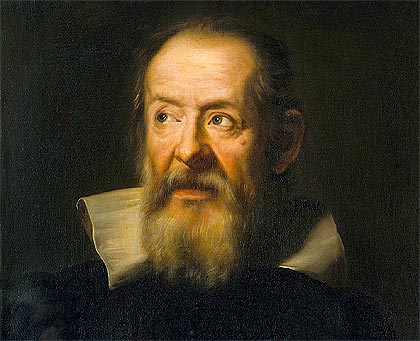

in 1610, Galileo published his Sidereus Nuncius (Starry

Messenger), describing the surprising observations that he

had made with his new telescope, among them, the Galilean

moons of Jupiter. With these observations and additional observations

that followed, such as the phases of Venus, he promoted the

heliocentric theory of Nicolaus Copernicus. And by the first

decades of the 17th century Galileo had become widely known

as the champion of the heliocentric revolution.

Next,

in 1610, Galileo published his Sidereus Nuncius (Starry

Messenger), describing the surprising observations that he

had made with his new telescope, among them, the Galilean

moons of Jupiter. With these observations and additional observations

that followed, such as the phases of Venus, he promoted the

heliocentric theory of Nicolaus Copernicus. And by the first

decades of the 17th century Galileo had become widely known

as the champion of the heliocentric revolution.

At this point,

the Vatican had had enough of Galileo's discoveries, and in

1616 the Inquisition declared heliocentrism to be "formally

heretical." Galileo went on to propose a theory of tides

in 1616, and of comets in 1619; he argued that the tides were

further evidence for the motion of the Earth.

The iconic astronomer,

physicist, mathematician and polymath continued his proposals,

accepted widely by fellow scientists, so that by1633 the Inquisition

was forced into a corner. But it came out swinging. That year

it put Galileo on trial, found him “vehemently suspect

of heresy,” and sentenced him to house arrest where

he remained until his death in 1642. His immensely popular

publication Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems,

published a few years before and strongly defending heliocentrism,

was the final straw. Further, the Inquisition banned all heliocentric

books and forbade any promotion of it anywhere.

But because of

the enormous popularity of cheap telescopes, the widespread

publication of discoveries by hordes of astronomers, and cascades

of sightings of asteroids, and meteors, the church condemnation

of heliocentrism fell on the deaf ears everywhere. It certainly

developed into an embarrassment for the church fathers whose

hubris militated against any kind of redaction.

And so it wasn’t

until 1758, more than 100 years later, that the church quietly

withdrew its foolish stridency. By this time observation of

planets, stars, constellations and navigation based on celestial

movement were easily the order of the day.

This narrative

serves as a good example of how verifiable fact can become

buried under a sea of distortion, lies, fake news, or whatever

you want to call it when a situation arises that contravenes

the policies of authorities in power . . . whether they be

religious clerics, economic dictators, or political strongmen

who broadcast that honest elections were rigged or who insist

that scientifically tested vaccines don’t work.

It took over 100

years for the geocentric ‘lie’ to be finally debunked

(actually, I’m wrong because I’m sure if you wander

about you will find individuals who still vehemently deny

that the earth revolves around the sun) . . . how long will

it take for the present day politicians’ lies to be

uncovered and rejected?