Once a festival

survives its early years and begins to grow deep (natty) roots,

the perennial challenge is how to keep it fresh, exciting and

relevant.

It would be very

easy for a festival as prestigious as Montreal’s Festival

International Nuits d’Afrique to get by

on its reputation and let past success determine its future.

But the programmers are well aware that ‘change’

(flux) is the single most important constant in the universe,

and by keeping abreast of how the forms and formats of music

are constantly evolving, Les Nuits makes sure that it remains

at the forefront of what is happening on the ground and in the

studio as it concerns Africa’s indigenous music and its

quasi-conjugal relationship to world music; which is why, after

33 years, it continues to be one of the great voyages of discovery.

It’s not a coincidence that many African-born musicians

have decided to make Montreal their home. They know in advance

there will be both venues and audiences for their new ideas,

many of which will be programmed into the summer festival.

Despite the recent

(2017) changing of the guard in respect to its programming director

(Colin Rigaud takes over from Frédéric Kervadec),

Les Nuits d’Afrique continues to feature engaging new

music as well as the constant reminder that behind every music

there is a long-standing tradition.

From

the highly personal, plaintive urgings of Mali-born albino Salif

Keita to the progressive reggae of Jamaica’s Jah9, there

is a vital link. Geographical and generational gap notwithstanding,

what they both share is having been at the wrong end of the

black and white intolerance spectrum, and being able to transmute

those negative experiences into the highest art.

From

the highly personal, plaintive urgings of Mali-born albino Salif

Keita to the progressive reggae of Jamaica’s Jah9, there

is a vital link. Geographical and generational gap notwithstanding,

what they both share is having been at the wrong end of the

black and white intolerance spectrum, and being able to transmute

those negative experiences into the highest art.

The counterpoint

to being black in America is to be albino in Africa. Noah Deshe’s

haunting film, White

Shadow, recounts in excruciating detail the challenges

of albinos in Ethiopa who are hunted for body parts and their

putative medicinal properties. In that same prejudicial spirit

that knows no borders, Mali's melanin-challenged Salif Keita,

a tribal prince by birth, was exiled by his family, and like

many under-appreciated American jazz musicians ended up settling

in Paris where his career took off.

Cape Verde’s

Elida Almeida informally opened the festival at the legendary

Club

Balattou. Her infectious enthusiasm and strong

voice underpinned original material that embodied both the folk

spirit of the island and the impact of globalization. Not to

be discounted was her stage presence and a smile that could

light up the darkest night which had the photographers reaching

for their best lenses. Of note was the time and space she gave

to her inventive and complicit guitarist Hernani Almeida.

Among the many

surprises of Les Nuits was the vagrant voice and compositions

of Jamaica’s Jah9 (Janine Cunningham). Unlike most reggae

singers, for whom the genre is a self-contained world with its

set-in-stone protocols, Jah9 makes traditional reggae a point

of departure, allowing it to absorb  and

react to the changing world around her, a world that now includes

women’s voices who, en masse, are finally challenging

the once inviolable male dominated world order.

and

react to the changing world around her, a world that now includes

women’s voices who, en masse, are finally challenging

the once inviolable male dominated world order.

Much like the Delta

blues had to leave the Delta to become everyone’s blues,

reggae, by responding to the world as it turns mostly sour-sop,

is no longer a strictly Jamaican product. Sometimes Jah9 would

slow things down such that the reggae seemed to waltz or sway,

transporting the listener to an enchanted place where the normally

thumping bass was reduced to a whisper. Her highly inventive

intros and memorable codas were the pitch-perfect bookends to

carefully conceived lyrics. But it was her voice, clean and

confident, that kept everything in its sure orbit around her

musical and political agenda. Sometimes she would extend a note

to emphasize a lyric, and then snap it back like a whip before

down-shifting into another tempo. Looking ahead everything looks

good for Jah9 whose already significant original material is

going to get better and take her to places where most reggae

composers fear to tread.

The best way to

capture the hybrid music of Mali’s scintillating Songhoy

Blues quartet is to situate them in their native land where

the lead singer, Aliou Touré, absorbs the style and substance

of griot jala while the guitarist, Garba Touré, develops

a liking for the quickly expiring plucked note as opposed to

the longer held western one. After an extended pit-stop in the

Mississippi Delta, the group cozies up to a high powered electrical

grid, and then does due diligence at the altar of Jimi’s

“Voodoo Child.” Songhoy Blues is emblematic of how

music gets made these days – and without apology. And

at the end of the set,  whether

you want more or less of it, you won’t forget the sound

and their fury. They don’t ask “Are You Experienced?”

They are the experience, and one that begs to be repeated. Inspired

by Garba Touré whose notes exploded out of his guitar

like pods bursting with seed, Songhoy Blues scaled the heights,

and were one of the lights of Montreal’s African nights.

whether

you want more or less of it, you won’t forget the sound

and their fury. They don’t ask “Are You Experienced?”

They are the experience, and one that begs to be repeated. Inspired

by Garba Touré whose notes exploded out of his guitar

like pods bursting with seed, Songhoy Blues scaled the heights,

and were one of the lights of Montreal’s African nights.

There’s nothing

that compares with the uplift and exultation of discovering

new talent that represents a new way of interpreting the world.

This year’s pleasant surprise category award goes to Mali’s

Djely Tapa, who brings unwavering commitment and  incandescent

intensity to her original material. Blessed with a voice that

can burn-dry a lake under a monsoon sky, its ear-pleasing purity

and specific gravity are such that it keeps all other instruments

and listeners in mesmerizing thrall. Her mix of tradition and

urban coupled with intriguing time signatures translate into

a music that is winning over audiences wherever she performs.

Be sure to hitch your wagon to this rising star.

incandescent

intensity to her original material. Blessed with a voice that

can burn-dry a lake under a monsoon sky, its ear-pleasing purity

and specific gravity are such that it keeps all other instruments

and listeners in mesmerizing thrall. Her mix of tradition and

urban coupled with intriguing time signatures translate into

a music that is winning over audiences wherever she performs.

Be sure to hitch your wagon to this rising star.

In the first of

the free concert series that begins at the midway point of the

festival at the Quartier des Spectacles in downtown Montreal,

Benin’s Benin International Musical put sparks into the

night featuring hymns bathed in celestial harmonies that seamlessly

morphed into rap and hip-hop. This wasn’t just another

variation of World Music; the world’s music in all its

richness and variety was on display, and the audience lapped

it up and danced it up until closing time.

After spending part

of the day wandering through the narrow corridors of the fascinating

Timbuctoo market place, to visiting food stalls offering exotic

dishes from around the world, and finally checking out the numerous

ateliers and workshops where dancers and musicians explain the

origins of the incredible range of Africa’s stringed and

percussion instruments, the case can be made that Les Nuits

is as much a cultural as a musical event.

Based on a quick

scan of world culture as it settles into the 21st century, it

should be of interest and concern to everyone that the once

ubiquitous halo and hijab have been replaced by headphones and

iPhones. For better or for worse, nomadism -- man’s founding,

primordial first condition -- has given way to a 'monadic' existence

and the triumph of the self-sufficient individual (In Canada,

30% of adults live alone). And whether we rue or revel in these

developments, they are happening on our watch, and there’s

nothing like music to help us grasp what cannot be put into

words.

From Berber tent

music on the fringes of the Sahara to state-of-the-art digital

recording studios, Les Nuits is a chronicling of the world through

sound, and is arguably one of the most edifying music festivals

on both sides of the equator.

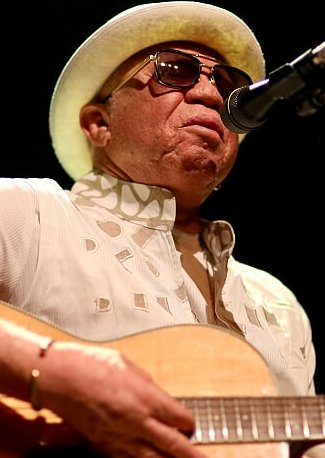

Case in point is

Algeria’s beloved Hakim Salhi. His music typically begins

in the mournful drone we associate with the Sahara and its unforgiving

climate, out of which is born the high pitched ululation (zagharit)

indigenous to the Arabic world. But with a sudden tweaking

of the tempo and cranking up of the horn section along with

thumping thumb-slaps to the bass, Salhi exchanges his camel

for a Corvette and in a matter of a few bars of music the listener

is yanked out of the medina and injected into a particle accelerator

– and pure joy erupts as the crowd goes crazy. Despite

the infectious beat of the bass and drum, Salhi has not betrayed

traditional Algerian music to win the favours of the West, but

rather he has added his voice to the great catalogue of Algerian

music now fully integrated into the modern world. Salhi, who

in 75 years from now will be regarded as traditional by the

new generation, is challenging cultural norms by lending his

voice to the one-world-order concept that is in slow but sure

ascendancy.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Like no other event

of its kind, the all-inclusive Festival International Nuits

d’Afrique is a celebration of the human spirit and the

transcending power of creation, where for 13 glorious days and

nights all differences and disputes are magically dissolved

in the universal language of music.

For this precious

experience, a huge jrejëf goes to festival founder

and recipient of the order of Canada, Lamine Touré and

his exceptionally dedicated and dynamic team.

Next year Les Nuits

turns 34, and that can’t come soon enough.

ADDITIONAL

PHOTOS