Nick

Catalano is a TV writer/producer and Professor of Literature

and Music at Pace University. He reviews books and music for

several journals and is the author of Clifford

Brown: The Life and Art of the Legendary Jazz Trumpeter,

New

York Nights: Performing, Producing and Writing in Gotham

, A

New Yorker at Sea,, Tales

of a Hamptons Sailor and his most recent book,

Scribble

from the Apple. For Nick's reviews, visit his

website: www.nickcatalano.net

This last phrase of the American pledge of allegiance aspires

to an ideal which the world is further from attaining than

ever before. Because of huge population increases, crowded

urban centers, increasing demi-wars and conflicts, complex

business and personal relationships, and corrupt governments,

any semblance of utopian justice seems more elusive than ever.

Instances of injustice

proceed from universally observable events to personal tragedies.

Examples of some that many have witnessed through the years

can help illustrate the scope of the issue.

On December 21,

1988 a U.S. jetliner exploded from a terrorist bomb over Lockerbie

Scotland killing 270 people including 189 Americans. Most

of the latter were college students studying abroad. Although

instances of terrorist bombings were common during that time,

I was particularly horrified because I was teaching my own

university students a travel course and we all traveled to

Europe together every spring for my seminar. As time went

on, investigations revealed that the bomb was planted by Libyan

terrorists.

It has been 32

years since this catastrophe and scores of international law

enforcement agencies have failed to bring the perpetrators

to justice. The case was recently reported by a PBS Frontline

journalist who lost a brother on the flight -- Pan Am 103.

Several of my students from that time emailed me to share

their despair at the injustice that has occurred for so many

years.

A few years ago

in these pages I wrote about the age old injustice associated

with the Nazis stealing art from all over Europe during their

reign of terror. I reviewed the George Clooney film The

Monuments Men which exposed some of the

more spectacular thefts: Michelangelo’s “Bruges

Madonna,” the Ghent altarpiece, Vermeer’s “The

Artist Studio”, and thousands of works by Renoir, Klimt,

Picasso and every important artist imaginable. The film noted

that much of the art would never be recovered.

At this writing,

a new book from Yale University Press, Goring’s

Man in Paris: The Story of a. Nazi Art Plunderer and His Word,

notes that the original thievery by Hitler’s henchmen

continues its legacy of injustice. Insidiously, during the

past 80 years scores of art dealers, gallery owners and even

famous museums have perpetuated this injustice enabling generations

of new thieves as they ignore factual reports of stolen art

in their possession.

Even when there

has existed advanced civilized mechanisms to counter the vast

array of social injustices history records colossal failures.

After the American civil war fought mainly to eliminate slavery,

the Congress enacted measures to enforce the liberation of

former slaves. These measures collectivized under the label

“Reconstruction” included the fourteenth amendment

(1868) providing former slaves with national citizenship and

the fifteenth amendment (1870) granting black men the right

to vote. These laws were included in the Reconstruction Act

of 1867 which needed the override of a veto by President Andrew

Johnson.

Northern military

units were dispatched to enforce the Reconstruction edicts

but after a few years the troops were withdrawn. Immediately,

southerners returned to their abuse of freed blacks; courts

and jurists seldom wavered from their urgent need to solidify

white supremacy. The judiciaries upheld a double standard

of justice for whites and blacks while police forces eagerly

enforced monstrous racial abuses. Enormous horrors occurred

from widespread lynchings to ordinary bus ride restrictions

of blacks.

These and vastly

more well-documented abuses continued unabatedly for over

30 years until Homer Plessy, a black train rider, refused

to sit in a train car for blacks. He brought charges challenging

the Louisiana Separate Car Act of 1890; this law was typical

of dozens of similar state and local segregation laws throughout

the south. Racial prejudice had been challenged in the network

of southern segregationist courts but no human rights changes

were ever made. However, Plessy’s case somehow made

it to the U.S. Supreme Court. At last, generations of racial

discrimination and hopeless injustice had a golden opportunity

to be changed. Despite a long history of essential human rights

violations, the American dream of “justice for all”

would be realized and blacks could finally receive the moral

compensation long denied them.

Incredibly, in

one of the blackest moments of U.S. Supreme Court history,

the Justices voted to support the network of southern state

segregation laws. In May 1896, in a 7-1 decision, the court

affirmed southern segregation practices maintaining that no

negro civil rights were violated in what they termed “separate

but equal” practices everywhere in the south. It wasn’t

until 1954 in the case of Brown vs. Board of Education that

the court, in a reversal, declared the “separate but

equal” doctrine unconstitutional. But to the present

day, systemic racism remains a practice in the darker corners

of American sociology.

The

shibboleth “Justice delayed is justice denied”

was iterated as far back as the Magna Carta in 1215. I chose

the above instances of injustice because, as in countless

other situations, the delays in righting wrongs continue daily

everywhere unabated.

The

shibboleth “Justice delayed is justice denied”

was iterated as far back as the Magna Carta in 1215. I chose

the above instances of injustice because, as in countless

other situations, the delays in righting wrongs continue daily

everywhere unabated.

Although, after

what we have just presented, universal injustice seems as

elusive as ever, some collective idealism does exist in the

international halls of power.  As

far back as 1899 in the convention of the first Hague Peace

Conference the Hague Tribunal -- the popular name for the

Permanent Court of Arbitration -- was established. Through

the decades The Hague court structure has been updated to

address classic cases of war crimes and other easily identifiable

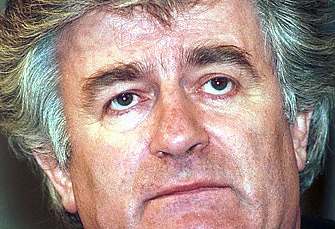

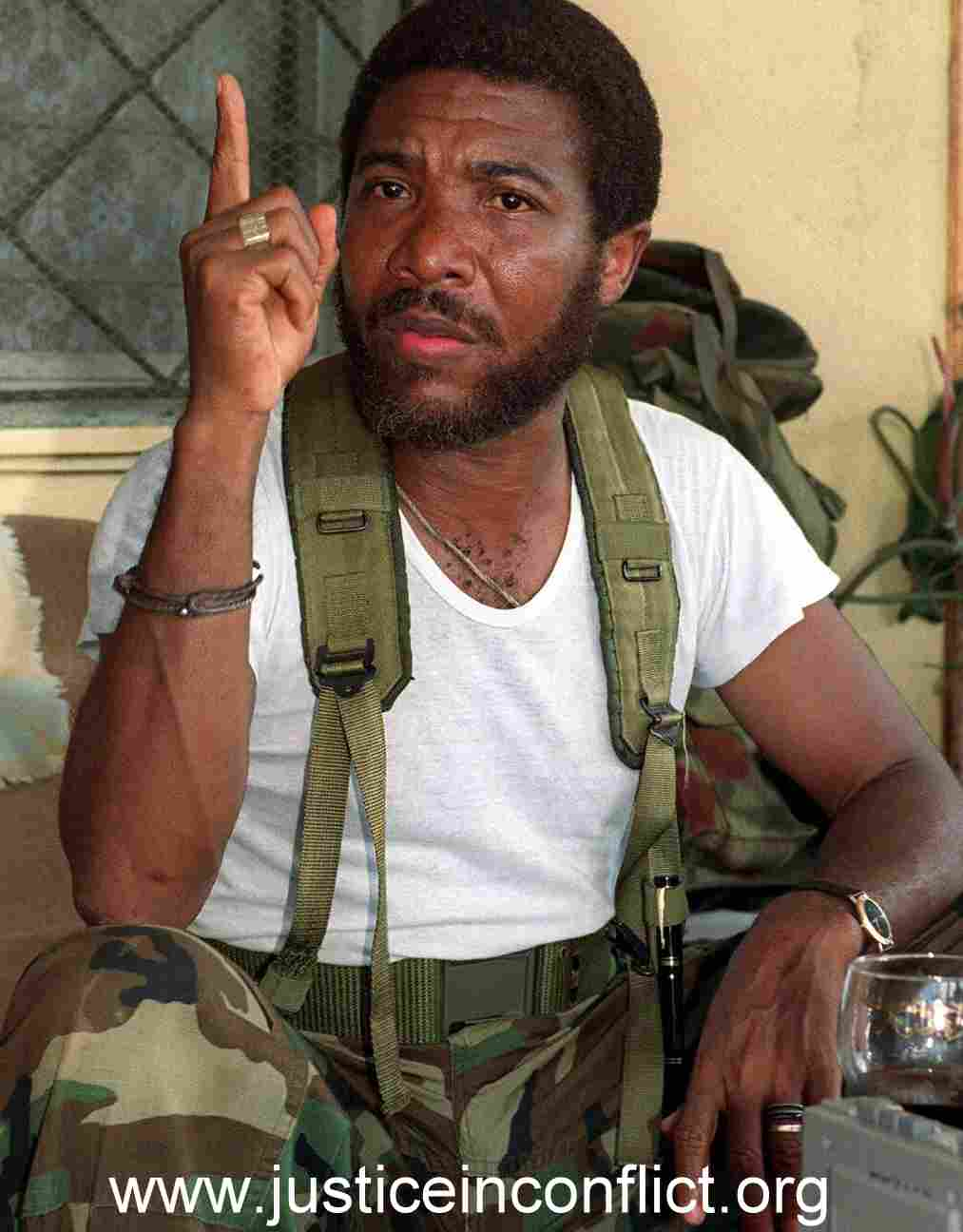

international injustices. In the recent past the cases of

Yugoslavia and Sierra Leone come to the fore with the Court’s

prosecution for the crimes of presidents Radovan Karadzic

and Charles Taylor. In another area under The Hague aegis

one of their organizations won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2013

for their “extensive work to eliminate chemical weapons.”

As

far back as 1899 in the convention of the first Hague Peace

Conference the Hague Tribunal -- the popular name for the

Permanent Court of Arbitration -- was established. Through

the decades The Hague court structure has been updated to

address classic cases of war crimes and other easily identifiable

international injustices. In the recent past the cases of

Yugoslavia and Sierra Leone come to the fore with the Court’s

prosecution for the crimes of presidents Radovan Karadzic

and Charles Taylor. In another area under The Hague aegis

one of their organizations won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2013

for their “extensive work to eliminate chemical weapons.”

But make no mistake.

Grossly insufficient support for work of The Hague structures

has been given by world leaders who have historically merely

paid lip service to its existence. Indeed, it remains the

only world organization and hope to remedy universal injustice.

As a new administration comes to Washington, hope exists that

President Biden will find time to initiate new support and

recognition of the work at The Hague.