more of my favourite things

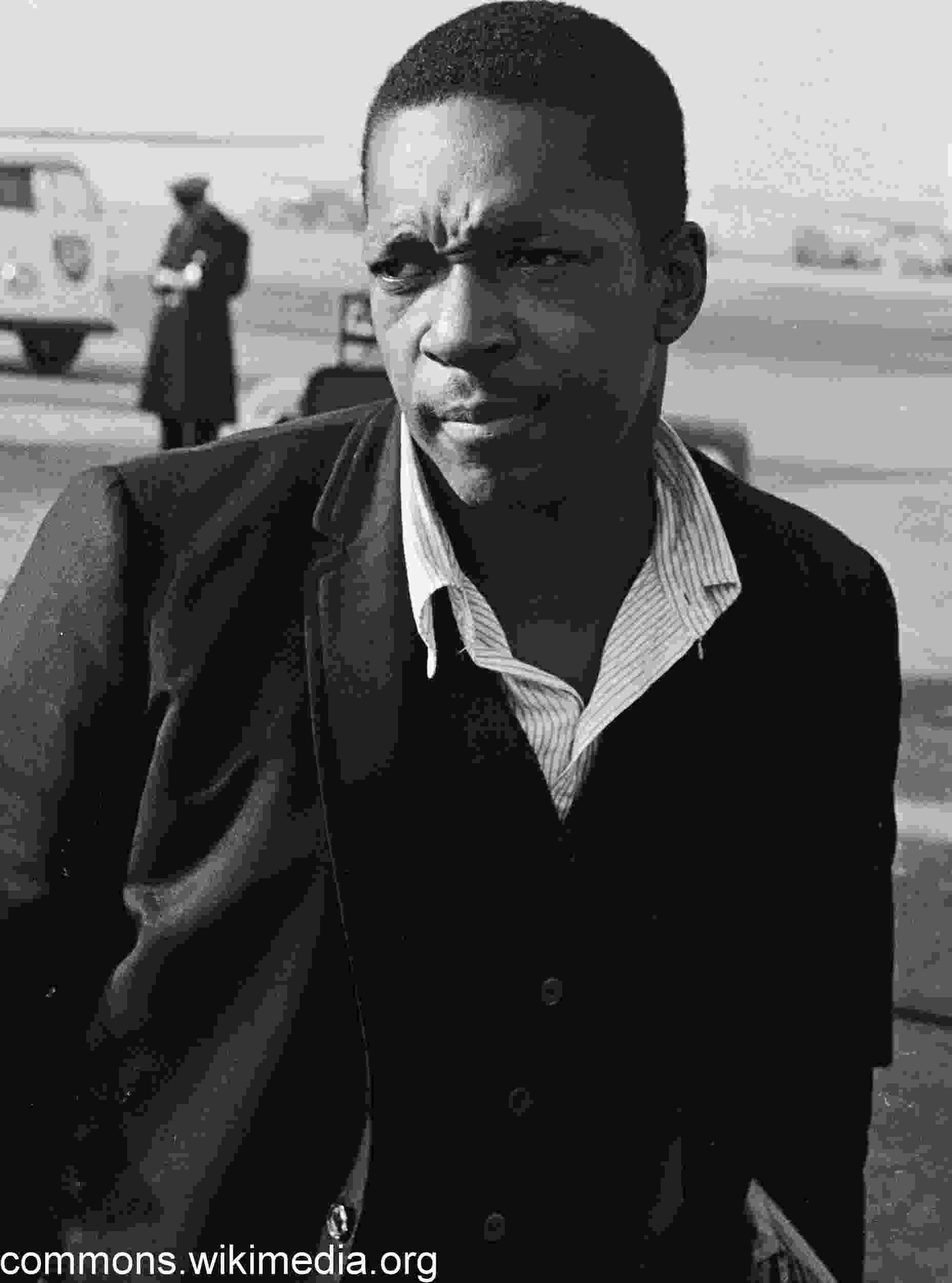

WHAT IF JOHN COLTRANE HAD LIVED

by

TED GIOIA

_____________________________________________________________________________

Ted Gioia is an American jazz critic and music historian

and author of The Birth (and Death) of the Cool, The History

of Jazz and Delta Blues, the latter two selected

as notable books of the year by The New York Times.This

articled originally appeared in The

Daily Beast and is reprinted with permission.

When

John Coltrane succumbed to liver cancer in 1967, he was at the

forefront of the jazz world. No saxophonist was more admired by

his peers or beloved by his fans. Coltrane was only 40 years old,

but he was a genuine jazz hero who had somehow crammed a whole

career of innovation and experimentation into the previous decade.

Coltrane’s

death cut short his music-making, but hardly put a dent into his

popularity or influence. You couldn’t escape it, no matter

where you went. In the late ’70s, I lived in Tuscany for

a half-year, and every month picked up a copy of Musica Jazz,

the Milan magazine that covered the Italian jazz scene. Each issue

included a listing of the best-selling jazz records in Italy,

and every month without fail John Coltrane’s A Love

Supreme was at the top of the chart — even though the

album was more than a decade old and from half a world away!

Coltrane’s

death cut short his music-making, but hardly put a dent into his

popularity or influence. You couldn’t escape it, no matter

where you went. In the late ’70s, I lived in Tuscany for

a half-year, and every month picked up a copy of Musica Jazz,

the Milan magazine that covered the Italian jazz scene. Each issue

included a listing of the best-selling jazz records in Italy,

and every month without fail John Coltrane’s A Love

Supreme was at the top of the chart — even though the

album was more than a decade old and from half a world away!

I recall

another telling incident, this time from the late ’80s,

when I spent a day auditioning saxophone students for a music

scholarship, and noted with interest that every one of these youngsters

seemed to have chosen John Coltrane as a major influence. Yet

not one of them was old enough to have heard him perform in person.

At that juncture, it was hard to find any aspiring saxophonist,

especially on tenor or soprano, who wasn’t a Coltrane acolyte.

I couldn’t

blame them. Most of us immersed in jazz, myself included, were

still focused on trying to understand and assimilate what Coltrane

had left behind. In fact, we were so focused on his legacy that

we spent little time wondering what he might have achieved if

he had lived longer. At times, it even seemed as if this remarkable

improviser had said everything he could possibly say on the horn.

Even if he had survived into old age, how could an artist with

so much music at his command have done anything more than repeat

himself?

But a

newly-released live album made during the final months of Coltrane’s

life forces me to revisit the question of what this path-breaking

artist might have achieved if he had hadn’t fallen victim

to cancer. This surprising music, recorded in concert at Philadelphia’s

Temple University in November 1966, has long been known to Coltrane

devotees — mostly through word-of-mouth, although poor-quality

bootlegs have occasionally circulated. Now Resonance Records,

in partnership with Coltrane’s label Impulse, has released

the complete concert on a double CD under the title Offering:

Live at Temple University. Finally jazz fans can judge this unusual

music for themselves.

The Temple University concert represented something of a homecoming

for Coltrane. In his mid-teens he had moved to Philadelphia, and

had gigged extensively in that city before getting the call to

join Miles Davis’s band in 1955. Now more than a decade

later, Coltrane was returning to Philadelphia as a world-beating

sax star and the most famous exponent of the avant-garde movement

in jazz.

But the

audience at Temple University wasn’t going to give Coltrane

a home town hero’s welcome. Even before the first number

was finished, audience members started walking out. Others “looked

as though they wanted to leave but sat rigid with disbelief,”

according to jazz critic Francis Davis, who was in attendance

that evening.

The

recording leaves us in no doubt as to the reason for this response.

Even by Coltrane’s standards, this music was transgressive

and disturbing. At a now famous moment during the concert, Coltrane

even put aside his saxophone to sing and pound on his chest—almost

as if he had exhausted everything the horn could do, and needed

to return to that most primal musical instrument of them all,

the human body.

Listening

to this performance almost a half-century after it took place,

I still lack coordinates from the jazz world with which to map

it. Instead I am reminded of my studies of shamans and trance-inducing

music, a subject that has been a key focus of my interest and

research in recent years. At Temple, Coltrane no longer operated

as a jazz artist improvising melodies, but more like a mystic

on a vision quest.

Researchers

such as Andrew Neher and Barry Bittman, among others, have confirmed

what non-industrial societies knew long ago — namely that

musical rituals have a tangible impact on the people who participate

in them. Brainwaves change, body chemistry is transformed, even

white blood cell count improves. The scientific and anthropological

studies agree on two key ingredients: the music must include drumming

for its full effect to be felt, and the “song” should

continue for at least ten minutes.

I’m

not surprised that both these elements figure prominently in Coltrane’s

late career music. Songs got longer and longer. A typical number

would last 20 minutes or more during this culminating phase of

his musical evolution. And much of his most inspired playing,

in his final years, came in the context of sax-drum duets. Coltrane

now sometimes performed with multiple percussionists, as at the

Temple University concert, even though many listeners found this

rhythmic layering overly busy and distracting. But, like a traditional

shaman, Coltrane clearly believed that the drums served as a springboard

to a higher order of engagement.

This

perspective helps me understand so many other peculiar aspects

of Coltrane’s late career work. Many fans have wondered

why Coltrane, at this stage, was so willing to invite guest performers,

of varying levels of talent, to join him on stage. Or why he seemed

to select accompanists based on his personal relationship with

them, rather than for their musical skills. And why did he spend

so much time in interviews talking about spirituality instead

of his famous substitute chord changes and other musical matters?

In fact, why did he seem so ready to abandon these same harmonic

advancements, the very stepping-stones that had taken him to the

forefront of the jazz world?

If you

view Coltrane as the “great man of jazz,” these decisions

make little sense. But if you view him simply as a “man

of greatness” perhaps we can understand both his path and

what he might have achieved if he had lived. Yes, we are rightly

skeptical with heroes of any sort in the current day, and any

reasonable person ought to hesitate before looking for gurus on

the concert stage. But John Coltrane may be the exception to this

rule.

He changed

the entire art form, but anyone who spoke to Coltrane for more

than a few moments could tell that his real goal was personal

transcendence. With Coltrane, the line between individual transformation

and musical advancement had always been a blurry one, but increasingly

so in the final years of his life. You simply can’t understand

his decisions on the bandstand or in the recording studio if you

view them merely as aesthetic responses to musical challenges.

Other, larger considerations inevitably intervened — spiritual,

interpersonal, socio-political. And I can only see those aspects

of his legacy deepening if he had lived into middle age and beyond.

So I

have a hard time envisioning Coltrane jumping on the rock fusion

bandwagon that swept through the jazz world in the months following

his death. But I can easily imagine him performing at the 1971

Concert for Bangladesh or at other philanthropic music events.

No, I can’t picture him participating in the retro jazz

movement of the ’80s, which celebrated a return to the ’50s

vocabulary that Coltrane himself had played a key role in subverting.

But I can imagine him mentoring younger players, or helping to

spur positive change in Africa, Asia, and other places where his

musical, spiritual, and political instincts would have found fertile

ground for growth and transformation.

When

I conjure up a mental image of John Coltrane at age 50 or 60 —

or even 88, as he would be if he were still alive and able to

celebrate his birthday this month — I still see him with

a saxophone in hand. But only some of the time. I suspect that

he would have found ways to make a difference in the world even

without a horn. And, most of all, I’d like to think that

some of followers — and in the jazz world their numbers

still are legion — would have followed him down that promising

path.

also by Ted Gioia:

The Backlash Against Jazz