Nick

Catalano is a TV writer/producer and Professor of Literature

and Music at Pace University. He reviews books and music for

several journals and is the author of Clifford

Brown: The Life and Art of the Legendary Jazz Trumpeter,

New York

Nights: Performing, Producing and Writing in Gotham

, A

New Yorker at Sea,, Tales

of a Hamptons Sailor and his most recent book,

Scribble

from the Apple. For Nick's reviews, visit his website:

www.nickcatalano.net

I am in Normandy

strolling among the dead in the American cemetery adjacent to

Omaha Beach. Seventy five years ago thousands of G.I.s came

here and died. As I move through the rows of gravestones on

an overcast day the silence is deafening. No one is here. I

gaze  painfully

at names on the graves and tears begin to well up in my eyes.

I ponder the numbers of the dead -- 9,388 soldiers are buried

here, 307 of them unknown. I think of their ages -- many youngsters

in their teens -- and I begin to sob. I randomly stop at a grave

and see a name -- Harry C. Clark, a fellow New Yorker in plot

H row 9 grave 30, a sergeant in the 747th Tank Battalion. Now

my sobbing deepens. I’ve been to

painfully

at names on the graves and tears begin to well up in my eyes.

I ponder the numbers of the dead -- 9,388 soldiers are buried

here, 307 of them unknown. I think of their ages -- many youngsters

in their teens -- and I begin to sob. I randomly stop at a grave

and see a name -- Harry C. Clark, a fellow New Yorker in plot

H row 9 grave 30, a sergeant in the 747th Tank Battalion. Now

my sobbing deepens. I’ve been to  Auschwitz,

lived through 9/11,written about both horrors while maintaining

my writer’s cool . . . but have never cried as hard or

as long as I can remember.

Auschwitz,

lived through 9/11,written about both horrors while maintaining

my writer’s cool . . . but have never cried as hard or

as long as I can remember.

Why is my sobbing so strong? I think about the soldiers buried

here mostly kids -- teenagers like the ones in my university

classes back home. These kids came here to fight Hitler and

most knew they would probably never come home. The soldiers

here had no agenda of imperialistic gain like other armies in

the miserable history of warfare. They were fighting for freedom

in the most honorable war effort in American history. As FDR

said “ . . . they fight not for the lust of battle. They

fight to end conquest. They fight to liberate. They fight to

let justice arise . . . They yearn but for the end of battle,

for their return to the haven of home . . . Some will never

return.”

I walk along the grass among the gravestones with Christian

crosses and Stars of David . . . the silence amplifies my gasps

and groans as I wipe away at the tears . . . and keep wondering

why I can’t stop whimpering . . . Maybe it’s because

all of this happened during the early years of my life . . .

maybe it’s because I know that so much of the sorrow of

75 years ago has been forgotten and that in another 75 years

it will become a dimmer blip in history. Maybe it’s because

all the films about Normandy enabled me to see soldiers faces

and hear their banter . . . it’s probably a combination

of all of this and also my horrible imaginings of what it must

have been like here as these youngsters died so violently by

the thousands.

I say a final goodbye to Harry C. Clark as I leave the cemetery

to move a short distance to Omaha Beach. I’m grieving

because I know that no one will ever write about Harry or mention

his name again . . .

On the beach I gaze across the Channel at the English coast.

I collect some beach sand as the waves lap against the shore.

I envision the LST’s at dawn on June 6th lowering their

bows and the soldiers jumping into the water as machine gun

fire from German bunkers slaughters many even before they can get onto land. As I walk

I can’t count all the bomb craters and artillery holes

that are still here from so long ago. I recall the words of

Colonel George Taylor,“ There are two kinds of people

who are staying on this beach: those who are dead and those

who are going to die. Now let’s get the hell out of here.”

I see the boys from the 1st and 29th American infantry divisions

crawling up the beach past Hitler’s Atlantic wall. The

broken and bloody bodies are flying everywhere as the ceaseless

mortar and machine gun fire rages on . . . New tears pour down

my cheeks.

slaughters many even before they can get onto land. As I walk

I can’t count all the bomb craters and artillery holes

that are still here from so long ago. I recall the words of

Colonel George Taylor,“ There are two kinds of people

who are staying on this beach: those who are dead and those

who are going to die. Now let’s get the hell out of here.”

I see the boys from the 1st and 29th American infantry divisions

crawling up the beach past Hitler’s Atlantic wall. The

broken and bloody bodies are flying everywhere as the ceaseless

mortar and machine gun fire rages on . . . New tears pour down

my cheeks.

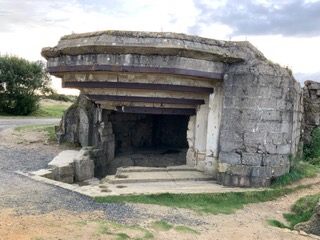

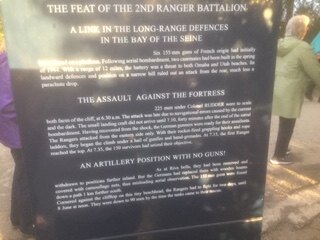

I walk a short distance and look up at the 100 foot cliff of

Pointe du Hoc -- a  promontory

where the Germans had installed their mightiest 155 mm cannon,

alone capable of sinking allied ships and completely halting

invasion efforts. At dawn on June 6th 260 soldiers of the 2nd

Ranger Battalion had incredibly scampered up the cliff without

suffering a single casualty. At the top they discovered that

the gun had been dismantled and was useless -- one of the inevitable

ironies of D-day. Their jubilation was short because as they

moved inland during the afternoon of the next day the German

artillery mowed them down and most of them died.

promontory

where the Germans had installed their mightiest 155 mm cannon,

alone capable of sinking allied ships and completely halting

invasion efforts. At dawn on June 6th 260 soldiers of the 2nd

Ranger Battalion had incredibly scampered up the cliff without

suffering a single casualty. At the top they discovered that

the gun had been dismantled and was useless -- one of the inevitable

ironies of D-day. Their jubilation was short because as they

moved inland during the afternoon of the next day the German

artillery mowed them down and most of them died.

As I walk over to the American museum, I stop along the path

to see photos and written profiles of soldiers who died at Normandy

. I stare at the photos thinking of these youngsters who would

never live a full life, would never enjoy family and friends,

would never love or laugh at memories in old age.

As I move on to the other beaches -- Utah, Sword, Gold, and

Juno -- my depression deepens because I know most of the world

has already forgotten about these dead soldiers. Tragically,

as the years pass so much of important history evaporates in

the collective unconscious. This inevitable forgetfulness is

one of the factors that leads to further war and killing.

In

the next issue I will retrace some of the strategies and events

that enabled the Normandy landing to penetrate the Nazi war

machine. Of all America’s war involvements, some of which

have questionable motivation, it stands as the most notable

chapter in the nation’s efforts to help free the world

from tyranny.