Imagine

every time you saw the number seven it was green or the number

four was blue. You would have a cognitive condition called synesthesia.

It is a very rare aberration -- but it is an aberration that

proves a point. Humans like to believe that perception is a

constant and objective. The reality is --that we are seriously

flawed instruments when it comes to reading the worlds we occupy.

A large bundle of loose electrical connections in our head suspended

in a gelatinous material process every sensation we feel. What

synesthesia proves -- every perception we have -- is defined

as much by us as by the reality we are perceiving.

Think

of how you experience reality as writing on a slate and every

experience you have adds information to that slate. Very quickly

you are forced to erase or just write over the experience. Not

only do you very quickly get detailed ornate and dense information,

but everything transcribed before begins to determine what is

written over it. Now consider that about a third of the experiences

you transcribe to this board are not real. The act of dreaming

is manufacturing perception. This manufacturing is ungoverned

by the laws of physics, time or gravity -- let alone manners

and decency.

Think

of how you experience reality as writing on a slate and every

experience you have adds information to that slate. Very quickly

you are forced to erase or just write over the experience. Not

only do you very quickly get detailed ornate and dense information,

but everything transcribed before begins to determine what is

written over it. Now consider that about a third of the experiences

you transcribe to this board are not real. The act of dreaming

is manufacturing perception. This manufacturing is ungoverned

by the laws of physics, time or gravity -- let alone manners

and decency.

Moroccan

born photographer, Lalla A. Essaydi lyrically illustrates this

dynamic with Converging Territories, #20. The c-print

depicts two naked women writing Arabic text in henna. One of

the women is slightly larger and lighter than the other. This

figure writes on the back of the smaller figure. The smaller

figure writes on a hanging sheet of white cloth. Essaydi takes

many of the ways in which people identify themselves and puts

them in a blender. Each element of the two figures has its own

signifier. Being naked suggests sexuality. The tone of the skin

suggests race. The writing reflects some religion or spirituality.

As these elements interact, they change each other. A prayer

written on flesh means something different than a prayer written

on cloth or paper. Essaydi constructs a metaphoric reference

between our bodies and our experience. We all know that shape,

size, color, gender and age of our bodies all affect we are

perceived. Essaydi shows that all of these elements also shape

our perceptions.

By

articulating this interaction so well, Essaydi’s work

serves as the master key for African Art Against the State,

Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, Massachusetts.

An exhibition of twenty artists combined shows how difficult

it is to cull experience from perception. What we experience

and our identity get folded into each other to the point of

being indistinguishable.

Essaydi’s

work deals with personal identity. Some of the exhibition’s

most fascinating pieces deal with public identity. African

Art Against the State includes several anonymous works.

These include Sande (Bondo) Society Mask, a carved

wooden mask, Mende People, West Africa; 2 Ogboni

Society Kneeling Figures, Male and Female, Yoruba People, Nigeria;

and Power Figure (Buti) -- Teke People, Democratic Republic

of the Congo. These pieces exemplify the dynamic Essaydi’s

work illustrates. Instead of linking personal subconscious these

works intergrate a collective unconscious in their pieces. Psychiatrist

Carl Jung coined the term to describe imagery that is understood

by an entire species -- as if all of the blank slates in the

world had images imprinted on them and were never totally blank.

These works seem to support Jung’s proposition. While

the specific iconography is unknown, the viewer can intuitively

read the works.

Two

artists directly reference this outsider aesthetic in their

work; Beninese sculptor Romuald Hazoumè and Belgian-Beninese

photographer Fabrice Monteiro. Hazoumè exhibits two ‘jerry’

plastic gasoline cans that are altered to look like masks, titled

Before 1999 and After 1999. After is made

from a can that seems burnt and partially melted. The artist

uses the handle to represent the bridge of a nose and the pouring

spout as a mouth. The connecting part of the handle can be read

as a very dominant brow line. The brow furled and the mouth

pierced as in a yell -- the work suggests an exaggerated aggression.

By creating images that tap not only our pre-verbal but pre-iconographic

mind, Hazoumè’s pieces operate as contemporary

interpretations of the source material.

Fabrice

Monteiro’s staged photographs operate more as an appropriation

of his source material. Instead of creating masks, the photographer

dresses models in elaborate outfits that mimic the same stylized

aesthetic. He contributes three pieces from his Prophecy series:

Untitled #1, Untitled #2 and Untitled # 6, all from

2014. In each he used the refuse of industrialized society to

create fantastic and horrific creatures. The figure in Untitled

#1 stands in a mound of midden that forms a skirt creating

the illusion that the figure has three-meter long legs. While

the work depicts what could be a dream, it is a very deliberate

and conscious work.

Monteiro

uses elements of the subconscious -- the distortion of reality

afforded in dream space, to create a surreal image. Two of the

exhibition’s artists use human sexuality in the same way

Georgia O’Keeffe’s flowers allude to vaginas. This

parallels how people think through the conscious and subconscious.

The exhibition includes two artists who invert how the audience

thinks about visual double entendre. Artist Zanele Muholi and

Yinka Shonibare use overt sexuality in their work. It is the

obvious text, presenting a subtext that is decidedly political.

Monteiro

uses elements of the subconscious -- the distortion of reality

afforded in dream space, to create a surreal image. Two of the

exhibition’s artists use human sexuality in the same way

Georgia O’Keeffe’s flowers allude to vaginas. This

parallels how people think through the conscious and subconscious.

The exhibition includes two artists who invert how the audience

thinks about visual double entendre. Artist Zanele Muholi and

Yinka Shonibare use overt sexuality in their work. It is the

obvious text, presenting a subtext that is decidedly political.

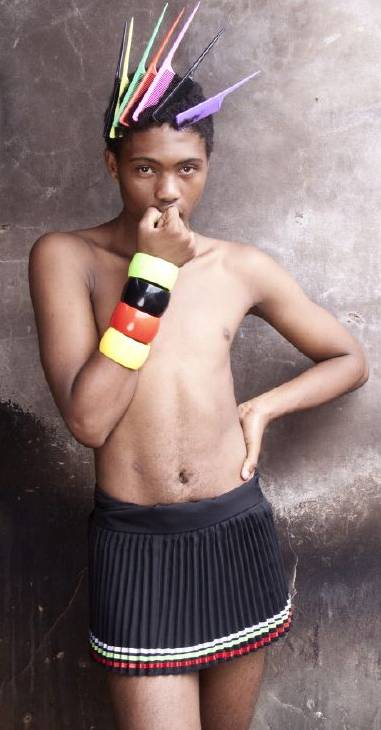

South

African photographer Muholi’s Mini Mbatha, Durban,

Glebelands, Jan. 2010 depicts a man dressed in a skirt

and bracelets with a five multicolored combs acting as a headpiece.

The piece belonged to the artist’s Beulahs (2006–2010)

series, which documented gay and transgendered men. The portrayed

man turns identity into a political statement. There is a deliberateness

to this figure. Dressed as a warrior the person asserts control

over their perception. This raises the act of sexual preference

and gender identity to a political statement.

While

Muholi’s portraits are intimate and specific, Yinka Shonibare’s

uses sexuality anonymously in Gallantry and Criminal Conversation

(Parasol), 2002, a sculpture showing two fornicating, headless

mannequins. Shonibare dresses the figures in Georgian fashions

made with faux African patterned cloth. The sexuality becomes

the work’s overt content. The work depicts misappropriations.

African textiles are rendered down to heavily patterned multi

hue cloths with no meaning. The European clothes are completely

antiquated and irrelevant to contemporary life.

Curator

Michelle Apotsos intentionally includes a pun in the exhibition’s

title. African Art Against the State leads its audience

to assume the exhibition is dealing with government. Walking

through the exhibition, it becomes clear it is subverting more

than political institutions. These artists undermine states

of consciousness and confidence. At it’s best African

Art Against the State forces its audience to consider that

what they think they know, may only be what they believe.

By

Anthony Merino:

Code

Replaces Creativity

Updating

Walter Benjamin

Ego

and Art

Nick

Cave & Funk(adelic)

Foucault

for Dummies