It

is with enormous emotion and respect

that I have chosen to dedicate this 28th annual festival

to the late Nelson Mandela.

Lamine Touré, President & Founder

Now

in its 28th year, Montreal’s Festival

International Nuits d’Afrique is uniquely

(epicentrically) positioned to showcase some of the latest developments

in music, which is why it is arguably the most distinguished

happenings of its kind.

Perhaps

more than any other place or continent, Africa’s music

is about its relationship with the rest of the world and vice

versa. So in a world that is becoming increasingly inter-connected,

where

borders are dissolving and unlike cultures are mixing it up,

we can expect African music to both reflect and be at the forefront

of these developments.

where

borders are dissolving and unlike cultures are mixing it up,

we can expect African music to both reflect and be at the forefront

of these developments.

The

concert by Banda Kakana was a highlight case in point. During

the set break, there were whispers that her sound wasn’t

African enough, especially for an opening concert. Which begs

the question: Is not her first obligation to be herself in her

music? To her major credit, she felt no qualms in acknowledging

that her influences have taken her a long way from Mozambique;

she refused to conform to the straight-laced  stereotype

of what African music should sound like, and instead offered

up a heartfelt evening of mostly original music influenced by

soul and R & B.

stereotype

of what African music should sound like, and instead offered

up a heartfelt evening of mostly original music influenced by

soul and R & B.

On

July 14th, while France was celebrating the 1789 storming of

the Bastille, Montreal, by special invitation, was stormed by

Cote d’Ivoire slammer Fabrice Koffy. Accompanied by a

first-rate, jazz-influenced guitarist (Guillaume Soucy), together

they broke all sorts of rules in a very agreeable, ear-opening

concert. Koffy sang/spoke in a quiet mellifluous voice such

that I was able to understand 80% of the lyrics -- in my second

language (French) no less. This opening act was followed  by

Fefe, a hyper, energetic hip-hopper from France whose large,

bellowing voice had the venue hopping and the floor buckling.

As if in answer to a basic requirement of melody, most of his

rap and hip-hop were inflected with soul and reggae.

by

Fefe, a hyper, energetic hip-hopper from France whose large,

bellowing voice had the venue hopping and the floor buckling.

As if in answer to a basic requirement of melody, most of his

rap and hip-hop were inflected with soul and reggae.

It

didn’t require more than 16 bars for Casuarina, an award

winning samba group from Rio, to win over a jam-packed Club

Mile End venue. The group’s cohesion and invention (sorely

missing on pitch just days earlier), was tweaked by complex

vocal harmonies and the tickly, prickly use of the cavaquinho

(think mandolin) and the bandolim (a bit like a banjo).

One

of the large questions this unique music festival asks is what

are the differences, if any, between American and African rap

and hip-hop? In America and in France, the rap is predominantly

mean and angry, it carries a gun and wants a revolution. But

anger alone cannot sustain the human spirit. African rap, which

is also angry, recognizes that there is a primordial  desideratum

for melody that cannot be indefinitely postponed or denied.

Everyday, people are fleeing

desideratum

for melody that cannot be indefinitely postponed or denied.

Everyday, people are fleeing the continent, taking to the seas and risking their lives because

they are destitute and suffering. African rap, which is more

complex than its American counterpart, offers not only an outlet

for the anger but a respite from the suffering. There isn’t

one of us who doesn’t long for the solace that only melody

can provide, the roots of which go back to those unremembered

lullabies sung to us out of the womb and into the hard-scrabble,

indifferent world. It could very well be that the African take

on rap and hip-hop not only fulfills the promise of the genres

but brings each to its apogee. From slam to rap to hip-hop,

there is an unbroken evolution towards melody and Africa is

spearheading this on-going development.

the continent, taking to the seas and risking their lives because

they are destitute and suffering. African rap, which is more

complex than its American counterpart, offers not only an outlet

for the anger but a respite from the suffering. There isn’t

one of us who doesn’t long for the solace that only melody

can provide, the roots of which go back to those unremembered

lullabies sung to us out of the womb and into the hard-scrabble,

indifferent world. It could very well be that the African take

on rap and hip-hop not only fulfills the promise of the genres

but brings each to its apogee. From slam to rap to hip-hop,

there is an unbroken evolution towards melody and Africa is

spearheading this on-going development.

In

its outdoor program, which begins at noon and runs non-stop

until late in the evening, the festival mostly serves as a staging

ground for up-and-coming, under-appreciated musicians and groups.

The voluptuous, deftly controlled voice of Cameroon’s

Veeby was an A-major discovery. Black Bazar and Zekuhl were

among the highlights, as were Guinea/Mali’s Doussou Koulibaly,

who plays the kamalé n’goni, and the urbane Senegalese

group Gokh Bi System, both of whom relied heavily on their rock

influenced guitarists.

Playing

her harp sounding n’goni like a rhythm instrument, Koulibaly’s

distinctly mellow African vibe was accompanied by a hard driving

rhythm section and the versatile guitar work of Aboulaye Koné,

who drew upon hard rock for most of his filling in and solos.

This deliberate mixing of unlike musical genres is a natural

consequence of diasporic communities looking to find their vital

center. In

the spirit of homage, let us recall that the fusion of lead

rock guitar with elemental African music can be traced back

to the ground breaking solo in Peter Tosh’s “Johnny

B. Goode.”

Playing

her harp sounding n’goni like a rhythm instrument, Koulibaly’s

distinctly mellow African vibe was accompanied by a hard driving

rhythm section and the versatile guitar work of Aboulaye Koné,

who drew upon hard rock for most of his filling in and solos.

This deliberate mixing of unlike musical genres is a natural

consequence of diasporic communities looking to find their vital

center. In

the spirit of homage, let us recall that the fusion of lead

rock guitar with elemental African music can be traced back

to the ground breaking solo in Peter Tosh’s “Johnny

B. Goode.”

One

of the essential general differences between the African and

western guitar solo is in the duration of the notes. The African

notes are very distinct and separate from each other, are of

shorter duration and disappear quickly, mirroring the evanescence

and impermanence that characterizes so much of Africa in terms

of its weather and politics.  All

this in sharp contrast to the western solo, whose notes are

electrically extended and often, for effect, bleed into each

other. The typical (can you feel my pain) western solo is self-referential

while the plucky African one evokes acceptance and resignation.

All

this in sharp contrast to the western solo, whose notes are

electrically extended and often, for effect, bleed into each

other. The typical (can you feel my pain) western solo is self-referential

while the plucky African one evokes acceptance and resignation.

After

an absence of two years, Madagascar Wake Up (Razia Said) was

back with a madly inspired evening of music. The multi-talented

group makes no bones about its political views as it concerns

runaway deforestation at the hands of big industry. The music

is a call to action, which began with the group’s gifted

guitarist Charles Kely, whose dazzling finger work and invention

is nothing less than mind boggling. That he is still not on

anybody’s radar screen is a mystery and music industry

shame. In a world where it’s not unusual to find iPods

in Berber tents, it is high time Kely become a household name.

What

distinguishes Nuits from the competition is its programming.

Never in the history of music has programming been such a challenge.

Nowadays, thanks to availability of state-of-the-art,  basement-friendly

recording equipment, almost everyone who aspires to music has

a CD (my 27th is in the works), which makes the programmers’

work more difficult than ever. Their near impossible challenge

is to comprehensively listen to not hundreds but thousands of

CDs from around the world and weed out the pretenders. And no

one does it better than Frédéric Kervadec and

his team. They do our homework and make it easy for us to discover

the latest and best in music, and enjoy a festival that is in

equal parts a listening pleasure and education.

basement-friendly

recording equipment, almost everyone who aspires to music has

a CD (my 27th is in the works), which makes the programmers’

work more difficult than ever. Their near impossible challenge

is to comprehensively listen to not hundreds but thousands of

CDs from around the world and weed out the pretenders. And no

one does it better than Frédéric Kervadec and

his team. They do our homework and make it easy for us to discover

the latest and best in music, and enjoy a festival that is in

equal parts a listening pleasure and education.

* * * * * * * * *

Between

an ideal world and the reality falls the music that wants to

bridge the gap.

Between

the music we know and music that wants to make us better than

what we are is Nuits d’Afrique.

So

until 2015, “This music always rescues me, there's a melody

for every malady.” (Passing

Strange).

Photos

© Hanna

Donato

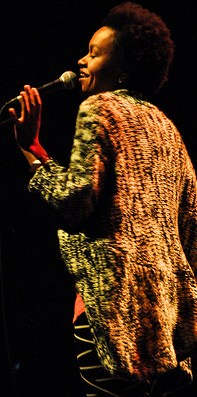

Flutist,

Doussou Koulibaly, Lorraine Klassen © Robert J. Lewis

2013

Nuit

d'Afrique

2012

Nuit

d'Afrique

2011

Nuit d'Afrique

2010 Nuit d'Afrique

2009 Nuit d'Afrique

2008 Nuit d'Afrique