|

|

michelle marder kamhi's

WHO SAYS THAT'S ART?

reviewed by

LYDIA SCHRUFER

____________________________________________

A while

ago I received a book that made me, by stages, angry, contrary,

furious, dismissive but, most importantly, thoughtful. The book,

by Michelle Marder Kamhi, is entitled Who Says That's Art?

A Commonsense View of the Visual Arts. The cover features

a detail of a Jackson Pollack painting, Marcel Duchamp's urinal

and Andy Warhol Campbell's soup can as examples of non art and

the premise of the book that we, the viewers of art, have been

duped into thinking that contemporary art is fine art.

The

book is well written, scrupulously researched and attempts to

convince the reader that most contemporary art is, in fact,

pseudo art. It is, according to Ms. Kamhi, an avant garde spurious

invention.  The

introduction states, " If art can be anything, then it

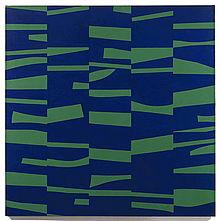

is nothing" and opens the discussion with Ellsworth Kelly

as an example of pseudo art. It is, in my opinion, an unfortunate

choice since Kelly is an icon of contemporary art; the beauty

and precision of his work is beautifully sublime. Ellsworth

Kelly' work is all about simplicity and under statement. Ms.

Kamhi insists that the viewer can't really be moved by non representational

art but I vehemently disagree: Just because a painting doesn't

have an object doesn't mean that it has no subject. The

introduction states, " If art can be anything, then it

is nothing" and opens the discussion with Ellsworth Kelly

as an example of pseudo art. It is, in my opinion, an unfortunate

choice since Kelly is an icon of contemporary art; the beauty

and precision of his work is beautifully sublime. Ellsworth

Kelly' work is all about simplicity and under statement. Ms.

Kamhi insists that the viewer can't really be moved by non representational

art but I vehemently disagree: Just because a painting doesn't

have an object doesn't mean that it has no subject.

According

to Ms Kamhi we've all been duped by art critics and the whole

art machine into accepting that most art being produced today

is a “. . . sick joke or momentary aberration” which

seems to suggest that contemporary non representational artists

are spending months and years making art with the sole purpose

of making money and pulling the wool over our eyes. Although

I do agree that some artists are making art that is difficult

and even, in many cases, off-putting I do not agree in the conspiracy

theory. Most artists are passionate and engaged in their work.

Much contemporary art is about visual metaphor, challenging

perception, exploring shape, colour and space. It is not about

creating the illusion of a three dimensional world. Serious

artists push the boundaries and therefore, often, incite derision

and discussion. Artists react to their environment and their

times. Good art cannot be a constant reiteration of what has

already been said. We appreciate the work of the old masters

but their weltanschauung (world view) is no longer indicative

of our reality. A changing world is not conducive to the pastoral

masterpieces of the past because relevant art reacts and engages

and makes us think about the here and now.

Ms.Kamhi

posits that non representational art cannot inspire emotional

reaction; again, I disagree. When I am in front of, for example,

a work by Rothko I'm enveloped in an environment of vibrating

colour. The work is not telling a story or representing allegory

so therefore, according to Ms. Kamhi, contemporary non representational

art can only function as decoration and not as a vehicle of

meaning.  I

would invite the viewer into an installation by Anselm Kiefer

and remain unmoved by the spiritual content of his textures

and scale of the work. I

would invite the viewer into an installation by Anselm Kiefer

and remain unmoved by the spiritual content of his textures

and scale of the work.

Non

representational art is not a new concept. Artists have been

exploring different methods since humans scratched their first

images onto cave walls. Every artistic endeavour that challenged

the status quo has been denigrated as an aberration when it

first appeared. Much of the art that we now revere was initially

laughed at and considered a fleeting trend. The fact is that

art is always filtered through the time in which it is created.

Artists react to changing times. A world experiencing war and

destruction is not going to produce biblical, Renaissance allegory

because it isn't relevant to the times.

Twentieth

century art requires a different language and means of representation

than nineteenth century art in order to accurately, convincingly

reflect the zeitgeist. Art after 1945 would not cohere with

a bucolic landscape painting because it would strike the eye

as false. An angry expressionistic portrait by Willem DeKooning

is not, perhaps, as easy to look at as a neo classical portrait

by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres but it is no less relevant;

in fact, I would say the neoclassical portrait is considerably

more 'decorative' and less emotional. Experimentation is and

always has been of paramount importance to living, evolving

art.

I do

agree with Ms. Kamhi that many gifted representational artists

are being ignored by the art establishment but that doesn't

mean that the great majority of cutting edge artists are any

less valuable. Ms. Kamhi includes Matisse, Duchamp, Picasso

et al in her list of 'pseudo' artists. She dismisses all isms

since neoclassism. “The Armory Show of 1913 was a travesty

that sounded the death knell for traditional art." Ms.

Kamhi also decries public funding for non traditional art which

suggests that according to her only 'traditional' and safe non

confrontational should be encouraged. Ms. Kamhi states, "My

primary aim in this book has been to discredit the pseudo art

that now dominates the international artworld." The most

recent artist that Ms. Kamhi allows into the pantheon of real

artists is Paul Gaugin, who's work she loves, even though he

was considered a fauve (wild beast) during his lifetime.

If

one agrees with the premises of this book one must assume that

all the major and minor art collectors and donors and art endowments,

Guggenheim, Rockefeller etc. have been swindled into believing

and endorsing abstract art and should instead be concentrating their efforts on pretty representational paintings

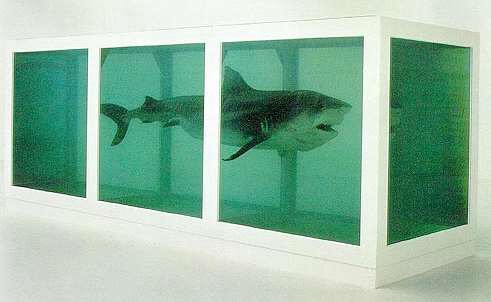

and sculptures. One may not care for Damian Hurst's pickled

shark or Tracy Emin's installations but experimentation is an

integral part of art evolution and certainly encourages dialogue

and discussion as does this book.

be concentrating their efforts on pretty representational paintings

and sculptures. One may not care for Damian Hurst's pickled

shark or Tracy Emin's installations but experimentation is an

integral part of art evolution and certainly encourages dialogue

and discussion as does this book.

For

a quick introduction to understanding and appreciating abstract

art go to YouTube and find “The Rules of Abstraction”

narrated by Mathew Collings; a 6-part overview. That and the

endless links thereafter are a great beginning to educating

ourselves about contemporary art and why it developed.

COMMENTS

Author Michelle Kamhi

responds:

I appreciate Ms. Schrufer’s observation that my “well

written” and “scrupulously researched” book

made her not merely “angry . . . [and] dismissive but,

most importantly, thoughtful.” Since Who Says That’s

Art? challenges the fundamental assumptions of today’s

artworld, I expected it to anger a good many readers who share

those assumptions. If it makes at least a few of them, like

Ms. Schrufer, more “thoughtful,” I will be quite

happy.

To correct the record, however, I must note some egregious

errors in the review—errors that might make my contrarian

position seem beyond the pale even to readers who would otherwise

sympathize with it. First, Matisse and Picasso were not included

in my “list of ‘pseudo’ artists.”

My critical comments on them applied to certain works, not

to their entire output. Moreover, I applied the phrase “sick

joke or momentary aberration” only to Damien Hirst’s

shark in a tank, not to all “contemporary art.”

Even more troubling is Ms. Schrufer’s apparent implication

that I stated: “The Armory Show of 1913 was a travesty

that sounded the death knell for traditional art.” Those

are her words, not mine. What I did argue, in part, was that

the proper lessons of 1913 are not those found

in standard art histories, which tend to regard it as a watershed

moment for avant-garde work. . . . [T]he so-called philistines

who rejected the most “progressive” innovations

in the Armory Show were less benighted than standard accounts

have tended to claim.

The responses of prominent conservative critics, for example,

were often thoughtful, nuanced, and remarkably prescient.

Like the public, those critics aimed their strongest objections

not at Cézanne, Van Gogh, and Gauguin (artists who

have since gained favor with a fairly wide public) but at

the more extreme inventions of “cubism,” “futurism,”

and “fauvism.”

The Armory Show’s most universally reviled

works were Matisse’s fauvist Blue Nude . .

. and Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase.

. . . Yet even today’s admirers of Matisse’s Blue

Nude characterize it as “grotesque” (why

should such a quality be admirable?).

. . . Moreover, cubism proved to be a dead end even for some

of its most prominent defenders and practitioners. . . . And

pieces such as Picasso’s cubist sculpture Head of

a Woman and his painting Woman with Mustard Pot

. . . are still troubling. . . . Why? Because cubism’s

stylistic tricks arbitrarily fragment perception. They thus

obscure rather than illuminate the subject, thereby working

against an essential purpose of figurative art.

. . . [W]hile art historians and other artworld “cognoscenti”

view Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase

as a work of seminal importance, how many ordinary art lovers

share that view? Duchamp himself quickly abandoned that painting’s

cubist-futurist style, turning instead to his nihilist anti-art

gestures in the form of “readymades.” The historic

import[ance] of his Nude stems not from any inherent

worth as art (it has none) but from the license it—along

with other radical works in the Armory Show—gave to

the notion that anything goes in the world of art.

Nor did I argue that “non-representational art cannot

inspire emotional reaction.” What I argued is that the

particular emotions inspired are often sharply at odds with

the artist’s intentions. Ms. Schrufer’s response

to Ellsworth Kelly’s work is a case in point. She sees

“the beauty and precision of his work [as] beautifully

sublime.” However, sublimity generally refers

to things of high spiritual, moral, or intellectual value

and thus implies the mind’s deep engagement. In sharp

contrast, Kelly stated that he wanted his viewers to “turn

off the mind” and “look only with the eyes.”

Such an aim, I should note, reveals a fundamental understanding

of human perception. Visual experience inextricably involves

the mind. We are not built to “look only with the eyes.”

As I documented in the book, other basic misunderstandings

regarding perception, cognition, and emotion were involved

in the very invention of “abstract art” in the

early twentieth century. The failure of such work to convey

the artists’ intentions is, I argued, ultimately due

to those misconceptions.

Last but far from least, Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) is not

“the most recent artist” in my pantheon. Among

later artists cited favorably by me are painters Andrew Wyeth

(1917-2009) and Stephen Gjertson (b. 1949), as well as sculptors

Daniel Chester French (1850-1931), Anna Hyatt Huntington (1876-1973),

Harriet Whitney Frishmuth (1880-1980), Peter Cozzolino (b.

1934), and Meredith Bergmann (b. 1955). While their work tends

to be in a classically realist style, it is by no means merely

“pretty.” Like all art worthy of the name, it

embodies significant human values. As I argued:

Mimetic representation is not in itself the

goal of art. It is the indispensable means by which art performs

its psychological function.

The idea that art must be “confrontational,”

engage in “experimentation,” or “push the

boundaries” to merit our attention is a peculiarly postmodernist

notion—one of highly dubious validity in my view. I

also question the suggestion that there is a unitary zeitgeist

that all artists are bound to reflect.

In sum, contrary to Ms. Schrufer’s implication, I don’t

reject all “contemporary art.” What I do instead

is question the artworld’s prevailing view of what sort

of work that term properly encompasses.

shanazdion@.feedback.com

After reading the comments by Ms Kamhi, I agree with her.

Artists who smudge colours in the name of art are going to

be angry with this well written to the point book. Public

will love this book.

Arts

& Opinion, a bi-monthly, is archived in the

Library and Archives Canada.

ISSN 1718-2034

|

|

|