|

|

iggy azalea and the reality performance

THE NEW REAL

by

TARA MORRISSEY

___________________________________________________

Tara

Morrissey is a PhD candidate at the University of Sydney. Her

doctoral thesis on "Hip-Hop and Whiteness in Post-Race

America" is currently under examination. Her research interest

lies in African American Studies and American Cultural Studies,

with a specific focus on race and gender in the negotiation

of the American 'self.?'

I’m

the first of my kind,

You ain’t seen any?

Iggy Azalea,Murda Bizness’

Hip-hop

is a site of simultaneous representation and creation, reflection

and revision. The well-worn hip hop mantra of ‘keeping

it real’ simultaneously points to retention (‘keeping,’

maintaining) and the elusive ‘real’ in which the

culture has remained invested since its inception in the 1970s.

Hip-hop realness should not, however, be confused with realism,

but rather understood as a performative gesture. Likewise, the

twenty-first century proliferation of the reality television

genre celebrates the performance of the hyper-real in a way

that deliberately complicates traditional distinctions between

fiction and reality. In his manifesto on our contemporary infatuation

with reality, David Shields argues that “realness is not

reality, something that can be defined or identified. Reality

is what is imposed on you; realness is what  you

impose back.” Australian rapper Iggy Azalea, whose positionality

as a white female in hip-hop’s problematically black male-centric

space immediately troubles her bid for hip-hop authenticity,

presents a particularly interesting case for the ways in which

twenty-first century performances of the hyper-real in both

hip-hop and reality television converge. you

impose back.” Australian rapper Iggy Azalea, whose positionality

as a white female in hip-hop’s problematically black male-centric

space immediately troubles her bid for hip-hop authenticity,

presents a particularly interesting case for the ways in which

twenty-first century performances of the hyper-real in both

hip-hop and reality television converge.

Although

the particularities of what constitutes real-ness or authenticity

in the hip-hop context have in the years since the culture’s

documented beginnings been subject to a continuous process of

revision and redefinition, the ethos of being real and representing

oneself authentically remains an important part of hip-hop’s

politics of performance. The advent of reality television, another

pop cultural form transfixed by the space between performance

and reality, has, in turn, contributed to the proliferation

of the ‘real’ as a contested cultural space. The

phenomenon designated by Geoff King as ‘the spectacle

of the real’ particular to reality television thus provides,

I argue, a contemporary framework through which to revise and

re-envision realness and performance in twenty-first century

hip-hop. Hip-hop culture’s persistent preoccupation with

the real, and what Misha Kavka describes as the distinctly queered

instantiation of the real upon which reality television is hinged,

converge in the unlikely emergence of incredibly popular (albeit

polarizing) hip-hop reality shows such as Run’s House,

Flavor of Love, Love and Hip-Hop, and T.I. and Tiny: The Family

Hustle, amongst others. The correlation between these seemingly

distinct genres may then, as Kevin Young suggests, aid in understanding

what hip-hop actually means when it invokes the real:

Is it any accident that the rise of hip-hop realness precedes

and parallels that of ‘reality television’? . .

. The very term ‘reality show’ is a paradox of the

highest order, but does describe the mix of mask, role-playing,

and personae found on these forms of television —complete

with literal and societal scripts — and in far more subtle

form in hip-hop.

Notwithstanding

Young’s insightful contemplation of the concomitant explorations

of real-ness in reality television and hip-hop, however, the

relationship remains unexplored by scholarship from either discipline.

Hip-hop, a popularly masculinized space in which female performers

must negotiate and legitimize their presence, and the disparagingly

feminized realm of trash television and, by extension, its ‘trashy’

viewers, merge in this account in a way that highlights the

necessary constructedness of the real in both genres.

Throughout

the 1990s, hip-hop realness was predicated primarily on conformity

to a certain class-based, racial, and autobiographical authenticity.

Although these factors still contribute in a superficial way

to the aesthetic of hip-hop and its ‘cool’ marketability,

contemporary hip-hop culture evidences a more self-conscious

approach to realness and its paradoxical limitations, of which

scholarship on black music has long been aware. The problem

of authenticity in pop cultural performance is an intrinsically

racialized one, whereby, as Gilbert B. Rodman expounds,

mainstream rock, folk, and country musicians have much more

liberty to use the first person to utter violently aggressive,

sexually provocative, and/or politically strident words than

do artists working in genres like dance or rap. Which means

— not coincidentally — that the artists most frequently

denied the right to use the fictional ‘I’ tend to

be women and/or people of colour.

Michael

W. Clune also gestures to the inherent paradox at work in hip-hop’s

ethos of authenticity, namely that “the ascendant performance

conceit is that there is no performance going on.” Hip-hop

authenticity is therefore always already destined for failure,

wherein “the attempt to resolve the tension between the

formal ‘you’ of the rap lyric and the ‘you’

of the audience thus has the unexpected effect of turning the

once-celebrated figure of the rapper into rap’s ritualized

object of scorn.” Authenticity becomes the open secret

of hip-hop discourse, an acknowledged implausibility but an

omnipresent factor in the hip-hop performance. Young, too, understands

this performed real as part of a black American tradition of

counterfeit — the difference between ‘truthfulness’

and ‘troofiness’ that has proven to be a worthy

tool for both the literal and the figurative survival of black

America. “Since previously conceived notions of truth

have often oppressed black people,” Young writes, “the

counterfeit is a literary tool that fictionalizes a black ‘troof.’

Such a black, vernacular-based reality proves quite different

from a white-dominated historical, factual, and authenticated

one.”

That

Iggy Azalea is Australian renders her not only distant from

this cultural background to hip-hop’s investment in the

real, but also immediately ineligible for U.S. hip-hop’s

traditional neighbourhood-based channels of authentication,

or what Murray Forman terms the “extreme local upon which

[rappers] base their constructions of spatial imagery.”

Based in Atlanta, Georgia, signed to U.S. hip-hop label Grand

Hustle Records, and marketed within the Dirty South subgenre

of hip-hop with which the city is associated, Azalea complicates

hip-hop’s crucial investment in place of origin. Her disinclination

to identify as Australian hip-hop artist rejects essentialisms

of selfhood and self-representation and violates one of the

mainstays of hip-hop authenticity, the declaration of allegiance

to the rapper’s particular ‘hood. Indeed, in her

2013 song “Work,” the refrain of ‘no money/no

family/sixteen in the middle of Miami’ firmly establishes

the genesis of Iggy Azalea the rapper as ‘after’

her relocation to the U.S. Solidifying this erasure of Australian

influence is the fact that, unlike many other successful white

Australian rappers such as The Hilltop Hoods, Bliss n Eso, or

360, Azalea does not rap in an Australian accent. Instead, the

American twang of her delivery is most consistent with the Dirty

South tradition. That

Iggy Azalea is Australian renders her not only distant from

this cultural background to hip-hop’s investment in the

real, but also immediately ineligible for U.S. hip-hop’s

traditional neighbourhood-based channels of authentication,

or what Murray Forman terms the “extreme local upon which

[rappers] base their constructions of spatial imagery.”

Based in Atlanta, Georgia, signed to U.S. hip-hop label Grand

Hustle Records, and marketed within the Dirty South subgenre

of hip-hop with which the city is associated, Azalea complicates

hip-hop’s crucial investment in place of origin. Her disinclination

to identify as Australian hip-hop artist rejects essentialisms

of selfhood and self-representation and violates one of the

mainstays of hip-hop authenticity, the declaration of allegiance

to the rapper’s particular ‘hood. Indeed, in her

2013 song “Work,” the refrain of ‘no money/no

family/sixteen in the middle of Miami’ firmly establishes

the genesis of Iggy Azalea the rapper as ‘after’

her relocation to the U.S. Solidifying this erasure of Australian

influence is the fact that, unlike many other successful white

Australian rappers such as The Hilltop Hoods, Bliss n Eso, or

360, Azalea does not rap in an Australian accent. Instead, the

American twang of her delivery is most consistent with the Dirty

South tradition.

Australian

hip-hop, especially in its most commercially successful Anglo-Australian

incarnation, focuses its process of authentication on an imaginative

space in which hip-hop, as freestanding entity, is organically

and intuitively more real to the hip-hopper than mainstream

Australian cultures. Ian Maxwell’s important work on Australian

hip-hop practices presents a thorough and theoretically considered

analysis of the phenomenon of, in particular, white Australian

men in the outer Western suburbs of Sydney and their engagement

with the imaginatively evoked Hip-Hop Nation. Given the antipodean

absurdity with which the very existence of a flourishing hip-hop

community amongst white Australians might be interpreted in

the U.S. context, Maxwell’s study focuses on the steadfastness

and conviction of the subjects claiming allegiance to a Hip-Hop

Nation that is believed to supersede ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic

status and, indeed, nationality. “In no way,” he

argues, “might these processes [of authentication] be

seen as being (merely) culturally promiscuous, as celebrating

a postmodern valorization of the pastiche, a privileging of

the playfully eclectic for its own sake. On the contrary, the

use of the term ‘community’ precisely bespeaks a

concern with ‘the authentic,’ with tradition and

the fixing of values.” Maxwell points to this imagined

Hip-Hop Nation as crucial to the Anglo-Australian hip-hopper’s

perception of authenticity. In the absence of viable claims

to ethnic or experiential kinship in the “geographically

discontiguous, isolated, and multicultural” context of

Australian hip-hop, legitimacy of Australian hip-hop “largely turns

on the possibility of ascribing to local performance an authenticity

that had to be articulated to a discontinuous, geographically

remote narrative of origin.”

hip-hop, legitimacy of Australian hip-hop “largely turns

on the possibility of ascribing to local performance an authenticity

that had to be articulated to a discontinuous, geographically

remote narrative of origin.”

The

Hip-Hop Nation and its ability to mobilize those who hear its

call resonates with a diverse spectrum of Australian society

— the recent work of Australian-born rapper, activist

and academic Sujatha Fernandes, for example, testifies to hip-hop’s

multi-ethnic appeal as well as its international mobilization.

Further, Maxwell’s description of the self-authenticating

process of hip-hoppers in the Australian context resonates with

Azalea’s own account of her connection to U.S. hip-hop

culture. In the words of Maxwell:

an individual in Sydney, Australia, in 1992, could, they claimed,

get Hip-Hop Culture from a television video clip, and . . .

what they understood as being the essence of that culture is

so pure, so transcendent, that the being-ness of an African

American was seen, in effect, as an expression of that transcendent

ground, rather than the other way around.

Azalea

in turn describes her induction into hip-hop through a narrative

of self-alienation and online access to performance. “Sometimes

I would not go to school at all. I would be at home writing

raps, trying to be a rap star. I thought it was so cool. I would

see all the rap videos and watch them on YouTube,” and,

later, “Australia doesn’t have radio stations that

play hip-hop. You had to go on Google or look on Billboard to

see what was going on in America. I would go on MySpace to see

what other kids were listening to. I was just manning the internet

trying to find stuff that was cool.” The instinctive gravitation

towards Maxwell’s Hip-Hop Nation that Azalea describes

echoes Fernandes’s own narrative of hip-hop discovery

while viewing Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s

“The Message” music video: “There was something

fitting about my close identification with a fabricated product

that revealed so many truths.” The Hip-Hop nation forms

part of an important fable of hip-hop authenticity, a broader

marketing of the real that is mobilized not to enact stringent

guidelines as to who or what is real, but rather to incorporate

diverse hip-hoppers into a rudimentary shared mythology of sameness.

In

an interview with Australian hip-hop journalist Boss Lady, Azalea

can be seen to navigate simultaneously the twin imperatives

of Australian hip-hop and broader hip-hop authenticity. In an

attempt to justify her involvement in hip-hop and downplay the

incongruity of a white Australian woman in a culture dominated

by iconography of black masculinity, Azalea insists that although

hip-hop is, in her understanding, a black cultural product,

it has become, over time, “more than what it was before

and more than the main elements of it, you can have places for

other people to fit in.” Azalea’s attempt to account

for the evolution of hip-hop’s racial politics and thus

validate her claim to legitimacy — her right to hip-hop

— reveals two significant assumptions about race and its

relationship to hip-hop. First, the aforementioned problematic

myth-of-origin that hip-hop is black culture and second, that

her ability to speak both for and from hip-hop is determined

by a social performance of deference that underpins her responses

to the race question throughout this and other interviews. Indeed,

Azalea’s evident hesitation and the circumlocution of

her response typify awareness, rather than transcendence, of

her white positionality. Indeed, although Azalea suggests that

the importance of race in hip-hop’s process of authentication

has lessened as hip-hop culture has been diffused around the

world, she is, at the same time, eager to align herself with

blackness. In particular, Azalea’s body becomes the signifier

through which she is implicitly marketed as a hip-hop woman.

In

an interview with hip-hop magazine Complex, Azalea

offers the first of her embodied connections to blackness, and

one that is constructed as distinctly Australian. In a section

of the interview titled Growing Up in Australia, Azalea recounts

that “lots of the small towns in Australia have Aboriginal

names,” and that her town, Mullumbimby, is one of them.

She goes on to make more direct her association with Indigenous

Australia, asserting rather problematically that “if your

family’s lived in Australia for a long time, everyone

has a little bit of [indigenous blood]. I know my family does

because we have an eye condition that only Aborigine people

have.” The seemingly casual reference to possible indigenous

ancestry aims to do two important things. First, to indicate

blackness, and thus hip-hop authenticity, on a level distinct

from yet adjacent to U.S. blackness, and second, to lay claim

to an essential Australianness that irrevocably undermines accusations

that Azalea has rejected her Australian identity or failed to

authentically embody it, perhaps most notably through her accent.

She is also, importantly, distanced from whiteness as understood

in the U.S. context by association with an exoticized image

of Australia and connection to non-white indigenousness.

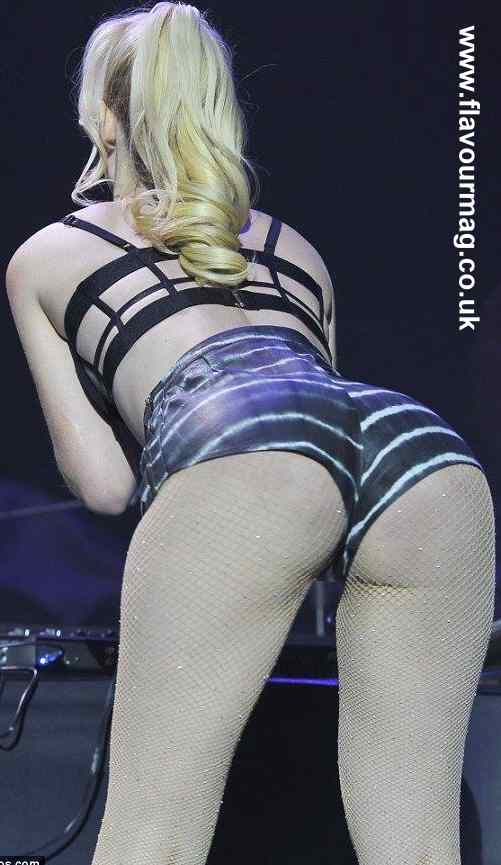

The

second, and more apparent means through which Azalea physically

aligns herself with blackness is through the shape of her body.

Boss Lady cites an apparent rumour as to Azalea’s  modeling

career, asking her, “I read that you were rejected as

a model at one point because you were too thick, is that . .

.?” Azalea responds that “it’s weird, though,

because I so don’t feel like I’m thick, I really

feel like people think I’m, like, bigger than what I am!

I’m not that big!” Focus on Azalea’s body

shape typifies not only the way in which popular culture emphasizes

female sexuality and sex appeal in its evaluation of female

performance, but also the particular lens through which hip-hop

scrutinizes and authenticates its female practitioners. Boss

Lady’s nod to the size of Azalea’s posterior is,

indeed, an authenticating gesture readily interpretable by hip-hop

audiences long-accustomed to hip-hop’s fixation with ‘bootylicious’

imagery. Like Nicki Minaj, and rappers such as Lil’ Kim

and Trina before her, Azalea’s videos are dominated by

close-ups of her buttocks and showcase a variety of suggestive

dances, techniques that unequivocally situate the female hip-hop

form within the stripper-sex kitten-seductress paradigm already

prevalent in male hip-hop videos. Reference to Azalea’s

thickness thus helps to sanction her participation in hip-hop

alongside her black female contemporaries by endowing her with

a dormant, interior blackness. Hip-hop’s interest in the

proverbial big butt, however, also complicates simplistic understandings

of realness in that the surgical enhancement of the historically

sexualized exotic female buttocks has become an increasingly

popularized and culturally recognized phenomenon. Physical blackness,

specifically black femaleness consistent with hip-hop’s

particular brand of realness can, in this sense, be manufactured,

as Imani Perry argues in her critique of hip-hop videos and

their unrealistic portrayals of black femininity. “Colour

is aligned with class and women are ‘created’ (i.e.

through weaves, pale makeup, and camera filters) and valued

by how many fantasy elements have been pieced together in their

bodies.” Azalea’s self-promotion as a white woman

with the desirable curves of hip-hop’s fantasy black woman

is thus incredibly loaded. modeling

career, asking her, “I read that you were rejected as

a model at one point because you were too thick, is that . .

.?” Azalea responds that “it’s weird, though,

because I so don’t feel like I’m thick, I really

feel like people think I’m, like, bigger than what I am!

I’m not that big!” Focus on Azalea’s body

shape typifies not only the way in which popular culture emphasizes

female sexuality and sex appeal in its evaluation of female

performance, but also the particular lens through which hip-hop

scrutinizes and authenticates its female practitioners. Boss

Lady’s nod to the size of Azalea’s posterior is,

indeed, an authenticating gesture readily interpretable by hip-hop

audiences long-accustomed to hip-hop’s fixation with ‘bootylicious’

imagery. Like Nicki Minaj, and rappers such as Lil’ Kim

and Trina before her, Azalea’s videos are dominated by

close-ups of her buttocks and showcase a variety of suggestive

dances, techniques that unequivocally situate the female hip-hop

form within the stripper-sex kitten-seductress paradigm already

prevalent in male hip-hop videos. Reference to Azalea’s

thickness thus helps to sanction her participation in hip-hop

alongside her black female contemporaries by endowing her with

a dormant, interior blackness. Hip-hop’s interest in the

proverbial big butt, however, also complicates simplistic understandings

of realness in that the surgical enhancement of the historically

sexualized exotic female buttocks has become an increasingly

popularized and culturally recognized phenomenon. Physical blackness,

specifically black femaleness consistent with hip-hop’s

particular brand of realness can, in this sense, be manufactured,

as Imani Perry argues in her critique of hip-hop videos and

their unrealistic portrayals of black femininity. “Colour

is aligned with class and women are ‘created’ (i.e.

through weaves, pale makeup, and camera filters) and valued

by how many fantasy elements have been pieced together in their

bodies.” Azalea’s self-promotion as a white woman

with the desirable curves of hip-hop’s fantasy black woman

is thus incredibly loaded.

Reality

television, unlike hip-hop, is a genre that is explicitly feminized

both in its promotion and in critical and popular evaluations

of its worth – or lack thereof. Kavka interprets the feminization

of reality television as part of a broader cultural imbrication

of televisual pleasure with the domestic sphere, explaining

that “during the nineteenth century the consolidation

of domesticity and consumption as ideological patterns occurred

specifically in reflexive relation to femininity, with the result

that the twentieth-century apparatus of television easily became

associated with, and devalued as, feminine practice.”

That a particular realm of televisual pleasure is relegated

to the demeaning category of trash “suggests that it perverts

the host medium by planting ‘trash’ as a literal

parasite on TV.” “The criticism,” Kavka continues,

“that reality TV is not in fact ‘real’ because

the shows are heavily manipulated (read: nobody actually lives

like that) is also dependent on the construct of a dumbed-down

viewership that conflates what plays out on one side of the

screen — framed as spectacle — with what happens

on the other — grounded in the experiential world.”

The scorn with which aficionados of underground or conscious

hip-hop interpret audiences of commercial hip-hop is similarly

grounded in a logic of intellectual inferiority at best, and

gullibility or naivety at worst. What dismissive readings of

both reality — trash — television and mainstream

hip-hop’s discourse of the real misinterpret, however,

is that the un-realness of the real is precisely the point,

or, in Kavka’s words, “the appeal of reality TV

lies precisely in its performance of reality in a way that matters.”

Indeed,

if the premise of reality television is its distinction from

fiction-based television, it is only superficially so. Ardent

fans of reality television understand and appreciate the manipulation

and editorial intervention at work in the production of televised

reality in the same way that soap audiences fully expect deceased

characters to resurrect, passionate affairs to perpetually begin

and end, and child characters to rapidly and inexplicably mature.

The same suspension of disbelief at work in traditional narrative

television remains a constant; what distinguishes the reality

genre is less its plot (scripted drama) than its setting (the

real world). As Shields elaborates, “we have a thirst

for reality (other people’s reality, edited) even as we

suffer a surfeit of reality (our own — boring/painful).”

The common line of criticism with which reality television is

derided, nonetheless, is framed as a kind of ‘outing’

of the manufactured or manipulated aspects of a given show —a

n exposÈ of the ostensible deception at play in the use

of the reality tagline. In short, the notion that reality or

the real can be performed, or can coexist with performance,

proves to be the sticking point for reality television’s

critical acceptance. Kavka’s interpretation of the reality

TV performance as “less a matter of “acting”

in the sense of simulation than of ‘acting out,’

a performance of the self which creates feeling” presents

a more workable understanding of the performance of authenticity

that correlates, in turn, with Maxwell’s description of

the freestyle rap practices of Australian male rappers. In both

scenarios, an external accusation of inauthenticity —

or, if not in so many terms, performance as the antithesis of

realness — is seen to destabilize the medium and, in so

doing, expose its fraudulence and concurrent ineffectiveness.

In Kavka, the scripted dimension and/or mediation of reality

television “is all television and no reality,” and

in Maxwell, the illusion of spontaneity in freestyle or battle

situations is its own undoing: ‘“But,” another

informant warns me, ‘you realize that none of them are

really improvising . . .’”

Surgical

cosmetic enhancement and the increasingly commonplace presence

of the plastic in the realm of the natural (much like the previously

discussed enhancement of assets in hip-hop) are coterminous

in reality television such as the Real Housewives franchise

with the fabrication and exaggeration of wealth and assets,

as well as the framework of gossip and back-stabbing from which

much of the dramatic appeal of the series is derived. The real

on offer, the audience comes to understand, is a constructed

real, mediated not only by the editorial tools of televisual

production but also, increasingly, by the housewives themselves.

Veneers become the open secret of the series that facilitates

our relation to and understanding of the show’s participants

and, concurrently, provide a space for intimacy between the

audience and the participant in the form of the promise of divulgement

or confession in the one-on-one cutaway sequences in which the

participant reveals her real response to the show’s dramatic

events. The openness of the franchise and its participants towards

surgical enhancement offers an unapologetically mediated interpretation

of the real, the premise being along the lines of, ‘I’m

not real but I’m real about it; I have nothing to hide.’

Within this framework the real becomes synonymous with transparency

and, as such, is negotiated not between the show’s participants

themselves but between the audience and each individual participant.

Real, in the culture of the series as a collective, is thus

dependent upon this reciprocal intimacy. What can it mean for

the frankness of artifice — real-ness — to replace

the truthfulness with which authenticity is traditionally configured?

In

her music video “Murda Bizness ft. T.I.,” Azalea

enacts a performance that interpolates the iconography of hip-hop’s

Dirty South with the markers of whiteness made luminous by the

explosion of reality television in popular culture. In effect,

Azalea incepts the reality television real (plastic whiteness)

within the real of ghettocentric hip-hop authenticity and, in

so doing, offers a conscious performance of realness that both

acknowledges her superficial incongruity in the masculinized

black space of U.S. hip-hop and suggests that performance of

a hyper-real authenticity of self is germane to hip-hop realness.

The video lampoons child beauty pageantry, an American subculture

that at the time of the video’s release was enjoying mainstream

attention as a result of reality television’s gonzo-style

explorations of its participants.

Pageantry,

itself obviously a performative practice, is rendered ludicrously

so in its pre-adolescent form: the aesthetic of the high-glitz

pageant, in particular, demands that the participant be appropriately

presented in full make-up, fake tan, hairpiece, false eyelashes,

acrylic nails, and the flipper, a removable veneer that gives

the appearance of adult teeth. The glitz pageant stands in opposition

to the lesser natural pageant, a binary that makes perfectly

clear the necessary, indeed compulsory, un-naturalness or constructed-ness

of the former. Lyrics such as,

These

other bitches think they’ hot?/Not really./She a broke

ho’/That’s how you know she’s not with me,’

‘I’m God’s honest truth,/They decide to lie/They

just divide they’ legs/I divide the pie’ and ‘Shit,

I’m IMAX big/You’re poster size’

mark

but a few examples of the rivalry by which “Murda Bizness”

is characterized. Teamed with images of glitz pageant children

that recall the dramatic rivalries enacted in Toddlers and Tiaras,

the performative nature of Azalea’s boast is exposed at

the same time as the very real effects of rivalry are nurtured,

developed, and deemed necessary to the successful performance

of femininity. The common thread of rivalry throughout hip-hop

and reality TV is similarly noted by Young in his argument that

the genres share particular interpretations of realness:

Nor is it a coincidence that participants in both rap and reality

TV — even when it is seemingly for love — refer

to their respective genres as the Game? If for rap it’s

called that because of the business (as well as its symbolic

relationship to the ‘drug game’ or the ‘fight

game’), both genres are highly aware of the parameters

(which are few) implied by the idea of a game, and refer to

realness and gaming in nearly the same breath, without irony

(which is otherwise rampant).

Rapper

T.I., whose own work – in particular his family-oriented

reality show T.I. and Tiny: The Family Hustle – has chronicled

his evolution from drug dealer to platinum-selling rapper and

self-professed family man, also appears in the video with his

stepdaughter Zonnique Pullins. The duo’s over-performance

of a pageant father and his diva-like daughter is of particular

interest in that it serves to distance hip-hop (via T.I.) from

the overt performance of pageantry at the same time as it troubles

the credibility of T.I.’s gangsta rap persona throughout

the remainder of the video. Indeed, the video presents a palimpsest

of real performance: the official performances on the pageant

stage; the cutaway interviews characteristic of reality television

in which participants play up their personalities in hopes of

making an impact on the show’s audience; the performance

of Azalea, T.I., Zonnique, and the rest of the cast in the pageant

roles; and, finally, the hip-hop performance by which the entire

work is framed.

Hip-hop’s

preoccupation with the real is compelling precisely because

of its instability, its constant recalibration and, importantly,

its awareness of the distinction between (per Young) the ‘truth’

and the ‘troof.’ Contemporary fascination with what

Shields terms “the extraordinary drama of lied-about ordinary

life,” crystallized in the increasing proliferation of

reality television, brings the long-discussed real of hip-hop

into a newly valorized position of prominence in popular culture.

Kavka’s assertion that discussion of the real is ultimately

invested in “value judgments that operate in binary relations”

whereby “inevitably, what is real is good, - a judgment

that works colloquially in its obverse, what is good is real

— while what is mediated is bad, and bad for you ‘

effectively summarizes the devaluation of reality television’s

performed real. Within its broader analysis of reality television

as a feminized and concurrently disparaged cultural space, however,

it may also prove useful in shedding light on the ways in which

realness is performed by hip-hop’s women. If, as Mark

Anthony Neal suggests, “ultimately all concerns about

authenticity in hip-hop begin and end with the fear of the proverbial

white rapper,” the recent emergence of the female white

rapper in mainstream U.S. hip-hop surely marks a crucial turning

point in hip-hop’s ongoing mediation of the real. What

remains to be seen, of course, is whether Azalea’s particular

mobilization of contemporary experimentation with realness in

its various pop cultural manifestations affords her longevity

in a hip-hop scene still skeptical of both white and, arguably,

female performance.

|

|

|