|

|

footloose and free

PATRICK LEIGH FERMOR

by

JOHN M. EDWARDS

_____________________________________

John M. Edwards middlenamed his daughter after his favourite

travel writer, Bruce Chatwin. His work has appeared in Amazon.com,

CNN Traveller, Missouri Review, Salon.com, Grand Tour, Michigan

Quarterly Review, Escape, Global Travel Review, Condé

Nast Traveler, International Living, Emerging Markets

and Entertainment Weekly.

“Soon

the delightful cry of ‘Delphinia’ went up: a school

of dolphins was gambolling about half a mile further out to sea.

They seemed to have spotted us at the same moment, for in a second

half a dozen of them were tearing their way toward us, all surfacing

in the same parabola and plunging together as if they were in

some invisible harness.” Patrick Leigh Fermor (Mani).

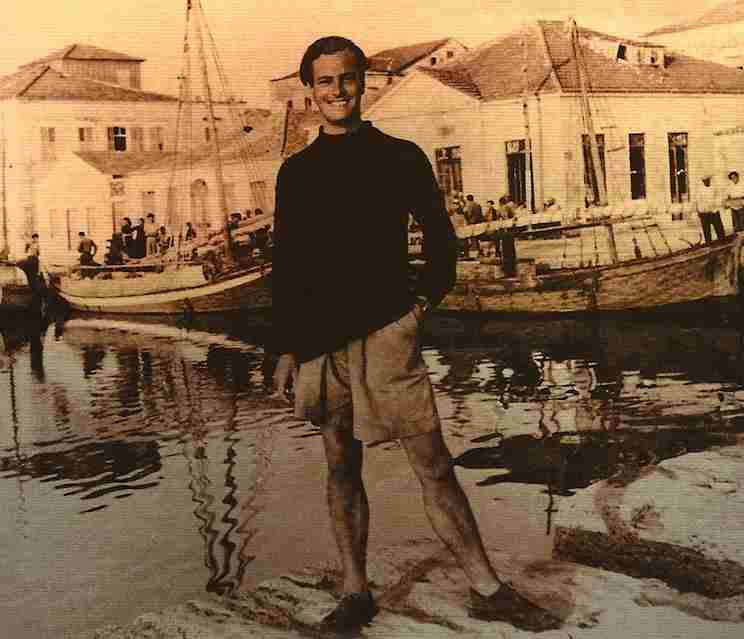

Patrick Leigh Fermor,

“Paddy” to his pals, is now a not-so-neglected name

to reckon with. Knighted in 2004, Sir Patrick Michael Leigh

Fermor (1915-2011) is considered by many, despite  the

Irish-sounding surname, to be England’s greatest travel

writer. Or as the BBC put it, a cross between “Indiana

Jones, James Bond, and Graham Greene.” the

Irish-sounding surname, to be England’s greatest travel

writer. Or as the BBC put it, a cross between “Indiana

Jones, James Bond, and Graham Greene.”

Even

so, Paddy -- author, scholar, soldier, spy -- gained lasting

literary acclaim only late in his life. He wrote about events

long past without the help of his lost journals (one of them

was recovered years later from a former mistress), ending up

writing with an intriguing mix of memory and imagination. His

nonfiction books are so well written, we feel like we have lived

through them ourselves.

Ordering

on Amazon, I dropped all of Paddy’s books in my shopping

cart and sped through checkout, ready to eye his entire oeuvre

exclusively for The Smart Set. As someone who actually believes

in the pagan gods of classical antiquity, as fallible as mere

mortals -- and a big fan of Henry Miller’s The Colossus

of Maroussi to boot -- I wanted to steep myself in Paddy’s

technicolour world of Mediterranean maenads lost in siren song

straight out of a Ray Harryhausen flick.

Best

known for his classic trilogy about his bildungsroman voyage

by foot across Europe -- A Time of Gifts (1977), Between

the Woods and the Water (1986), and The Broken Road

(2013), the last of which was published posthumously -- -Paddy

wrote about a “dream odyssey of every footloose student,”

according to his friendly rival Colin Thubron.

In

1933, Paddy, at the age of 18, set out to walk from the Hook

of Holland to Constantinople (the Philhellene’s term for

modern-day Istanbul, Turkey). A recent biography worth reading,

Patrick Leigh Fermor: An Adventure, by Artemis Cooper,

brings out the romantic tradition of the ‘vagabond’

in all of us, with colourful operatic characters, priceless

cultural artifacts, and vaguely improbable landscapes. Luckily,

Paddy waited over thirty years to release his finest narrative

work, sifted through mercurial memory and addended by artistic

license, rather than settling upon slapdash diary.

Home

for Fermor, as he has said more than twice, is “a base

to be nomadic from,” while he keeps company with tramps

and vagabonds, peasants and gypsies, and sleeps in uncomfortable

hayricks and baronial manors. We can almost visualize Paddy

right there in the thick of it, through the bohemian hobo haze

of Looney Toons-ish cartoon bums, usually sporting handkerchiefs

impishly tied to walking sticks.

Born

in London and died in Dembleton, Paddy ended up a decorated

war hero and pub raconteur. Farmed out to friends while his

parents were away in Raj-ruled India, Paddy did not properly

get to know his parents until the age of four. No surprise,

Paddy had a troubled youth, managing to get himself put into

a school for difficult children, before later being expelled

from the King’s School in Canterbury for holding hands

with a greengrocer’s daughter.

Paddy

describes his young self thus: “A cruel Fauntleroy veneer

masked a Charles Addams fiend that lurked beneath.”

His

only real ambition was to dance the Charleston at Roaring Twenties

Jazz Age parties and become a famous writer, which in 1933 took

him to boho Shepherd’s Market in London, and soon after

to the Balkans and Greece. What Colin Thubron called “the

longest gap year in history.”

To

retrace our trail a little bit, Paddy ranks right up there with

Paul Theroux, Erik Newby, and Norman Lewis. One of the so-called

Bright Young Things (which included Evelyn Waugh and Robert

Byron), Fermor’s fermented writings evidence fruit-forward

diction with a noble-rot nose on it, uncorked way past their

expiration dates.

No

other travel writer I can think of so effortlessly relies on

hindsight, such as the following excerpt from A Time of

Gifts at a “hoggish catalepsy” in the famous

Haufbrauhaus in Munich, Germany, right after Hitler came to

power in Deutschland in 1933:

I

was back in beer territory. Halfway up the vaulted stairs a

groaning Brownshirt, propped against the wall on a swastika’d

arm, was unloosing, in a staunchless gush down the steps, the

intake of hours. Love’s labour lost . . . Hands like bundles

of sausages flew nimbly, packing in forkload on forkload of

ham, salami, frankfurters, krenwurst and bludwurst and stone

tankards were lifted for long swallows of liquid which sprang

out again instantaneously on cheek and brow . . . It was some

terrible German saga, where snow vanished under the breath of

dragons whose red-hot blood thawed sword blades like icicles

. . . Or so it seemed, when the third mug arrived.

Paddy

offers an exceptional argument in favour of the vagabond life,

reminiscent of the tramps in Depression Era America and the

swells in Grand Tour Europe, sleeping in abandoned barns and

shepherds’ huts, as well as being invited into the landed-gentry

country homes of Central European aristocracy, such as Baron

Blah Blah Blah, serving up roast goose and decent claret. (I’ll

name just one of his myriad royal hosts with long unpronounceable

names: Baron Tibor Solymosy).

More

important, Paddy might be the very first genuine postmodern

backpacker, since he travels only with what he can carry in

a sturdy rucksack: clothes, letters of introduction, an Oxford

Book of English Verse, and a copy of Horace’s Odes.

Heavily influenced by Lord Byron, who died fighting in the Greek

War for Independence, and Robert Byron, who drowned in 1941

like Shelley from a torpedo blast, Paddy too had a Hellenic

obsession. He even reportedly swam across the Hellespont. Referring

to his Olympian Buster Crabbe-like feat he was confident that

he “had beaten all records for slowness and length of

immersion.”

After

at last arriving in Constantinople (now Istanbul since the eclipse

of Ottoman power)) in 1935, Paddy moved on to amazing Greece,

where he fell for his first love in Athens: a “Phanariot

Roumanian noblewoman named Princess Balasha Cantacuzene. They

set up shop in what would end up being Paddy’s second

home: Kardamyli on southern Greece’s Mani peninsula. They

then moved to Moldova right before calamity struck and ended

up being separated by jagged-jigsaw-puzzle-pieces of nation

states swept up in the worldwide conflagration.

During

World War II, as a newbie in the elite Irish Guards, Paddy was

involved in the Mission Impossible-y resistance in Crete against

the Axis powers. There, disguised in a sheepskin jerkin, he

helped with the war effort. Most famously, after three tours

in occupied Greece, one including a dramatic parachute jump,

in 1944 he kidnapped the German General Heinrich Kreipe.

Although

nothing quite beats the lyrical A Time of Gifts, all

of Paddy’s mostly successful work deserves mention. His

first book, The Traveller’s Tree (1950), is still

one of the best books ever written about the Caribbean. It won

the Heinemann Foundation Prize for Literature and was excessively

quoted by Ian Fleming in Live and Let Die. It was also,

despite its antique handling of racial issues, one of the first

books to mention the then-almost-unknown cult of Rastafarianism.

Judging by the book’s unique tone, Paddy was no stranger

to smoking the ganja, too.

His

next book, a vaguely disappointing first novel called The

Violins of Saint-Jacques (1956) is difficult to track down

either on the megastore bookshelf or the omniscient web. Almost

optioned as a film, the book went on to inspire an opera.

Ultimately

avoiding failure in the nick of time, Paddy married Joan Elizabeth

Rayner in 1968 (unfortunately right during the Sexual Revolution),

daughter of a noble family. Even though she died in June 2003,

aged 91, leaving the scholar-author-soldier decidedly bitter,

Paddy, under her influence, pulled off of his proverbial wagon

and released what is surely his best works, including the legendary

classic – alluded to ad nauseum -- A Time

of Gifts.

Obviously

influenced by Byron (Robert, not Lord), whose Athos

(1924) capitalized on the craze of Anglo classicist Philhellenes,

Paddy’s two books on amazing Greece, Mani: Travels

in the Southern Peloponnese (1958) and Roumeli: Travels

in Northern Greece (1966), are so exquisitely versed, even

though way over our heads linguistically, with colorful Greek

sur and place names and translations of poetically iconic terms,

that we all fall under an olive-grove trance. It is not what

is written that is important, but instead how.

A

fashion-conscious blade, Paddy, in Roumeli, commented

upon the rumour that the outlandishly dressed, ceremonial-dagger-wielding

shepherd nomads Savakatsans (Black Departers) of Northern Greece

never bathe from birth to death: “Oddly, they scarcely

smell at all, perhaps because of the time-stiffening carapace

of cloth which encases them.”

Although

separated by nearly a decade, the two Greek books make excellent

companions for the guest-room night table, dazzling us with

unfamiliar terms and hard-to-pronounce locations. (Paddy, although

occasionally supplying translations, seems to assume his learned

readership has studied at least some Greek). Amidst a backdrop

of hilltop Byzantine monasteries, hagiographic frescos of saints

and martyrs, and illuminated manuscripts, Paddy involves us

in his wayward philosophic peregrinations.

For

example, from Mani, in Missolonghi, Paddy goes looking

for Byron’s slippers; in Astakos (lobster in Greek), which

he doesn’t find, and on the Mani peninsula, he investigates

an ouzo-swilling Zorba the Greek fisherman claiming to be the

rightful heir to the throne of Byzantium, as well as unsubstantiated

rumours of a race of ancient Jews.

Rather

than relying on his lost diaries, whose absence “aches

like an old wound in cold weather,” he sifts his stories

into meme memoir, and then some. In Between the Woods and

the Water, for example, Paddy describes a chance meeting

in Bulgaria inside “an abode harmoniously shared by Polythemus

[the Cyclops from Homer’s The Odyssey] and Sinbad.”

Paddy relates in seductive (no: shimmering) prose:

I crawled the path and I pulled open an improvised door, uttering

a last dobar vecher [good evening] into the memorable cavern

beyond. A dozen firelit faces looked up in surprise and consternation

from the cross-legged supper, as though a sea monster or a drowned

man’s ghost had come . . .

While

re-reading Paddy’s essay collection Words of Mercury

(2003) in Knossos, Crete, at an al fresco taverna with excellent

retsina and grilled squid resembling asterixes, near the Temple

of Minos (of Minotaur fame), I became enthralled with his twice-told

tales of derring-do. It was here in 1944 that Paddy organized

the resistance against the Axis powers and kidnapped the German

General Heinrich Kreipe, with whom, after the war, he became

friends: both of them were, after all, fans of Horace. I felt

like I was frigging right there with the unfamiliar chthonic

Greek language spewing out of unemployed Golden Dawn peasants

mouths like black ink cartridges on an HP printer.

A

film version of Paddy’s wartime exploits in Greece called

Ill Met by Moonlight (1950), featured Dirk Bogarde as Paddy.

A recipient of both the OBE (Order of the British Empire) and

a DSO (Distinguished Service Order), Paddy was also an Honourary

citizen of Crete, where he was nicknamed, for no apparent good

reason, Michalis.

But

it is the spirit of the journey that counts. Paddy, dressed

in a sheepskin jerkin, “sleeps rough,” in barns

and monasteries, inns and hostels, caves and sheepfolds, and

people’s couches and under the stars. Often grubbing at

monasteries for silence and solitude, in order to write, Paddy

covers in his ode to unemployment what it is like to be young

and free abroad, much like the vagabonding ethic now propounded

by Rolf Potts. In the slender volume A Time to Keep Silence

(1957), Paddy relates how he sponges off monasteries, such as

the Benedictine Monastery at Saint Wandrille in Normandy, in

order to make sense of his world.

Rereading

Paddy’s impressive oeuvre of pulchritudinous prose and

Klephtic songs in an Oriental register, a roundup worthy of

repeating, abounding with footloose barons and beggars straight

out of a game of Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon, you will never

take your own two legs for granted ever again.

His

vanished Europe is a Grimm’s fairytale of an outcast depending

upon the kindness of strangers, a stroll from one Schloss to

another. Whether he is describing the pine-clad Carpathians

or glorious Black Sea, Eastern Orthodox monasteries or Byzantine

Empire onion domes, Paddy pads his text with the “rumour

of wolves” (or, werewolves) and the legacy of Germanic

Transylvanian Prince Dracula (or, Vlad Tepes [Vlad the Impaler]).

Paddy proves that even the best-laid plans may run off course,

like a colourful gypsy caravan from Universal Pictures. Especially

due to lack of funds.

In

Vienna, missing a monthly allowance payment of four pounds sterling

in the poste restante while staying in a Salvation Army Hostel

(much like a modern-day YHA joint), he is convinced by a fellow

flaneur named Konrad to sell sketches door to door.

Which is a better gig than Import-Export -- an international

euphemism for chronic unemployment.

Artemis

Cooper, Fermor’s biographer, says Paddy “smudged

the facts a little.” Much like his close friend Bruce

Chatwin, if not Lawrence Durrell, Paddy admitted that occasionally

he ad libs, such as a highly dubious account of riding through

the Hungarian puzhta by horseback. Response? Paddy “felt

the reader might be getting bored of me, just plodding along

. . . “ More than once, writes Cooper, Paddy’s “magpie

mind” adds details freely.

Until

2007, Paddy wrote all of his books in longhand, only reluctantly

turning to a typewriter in hopes of finishing his magnum opus

on vagabonding through pre-war Europe right before the mappa

mundi burst into flame. Until

2007, Paddy wrote all of his books in longhand, only reluctantly

turning to a typewriter in hopes of finishing his magnum opus

on vagabonding through pre-war Europe right before the mappa

mundi burst into flame.

A

five-pack-a-day smoker, whose photos frequently feature him

stylishly holding a dangling cigarette like Rod Serling narrating

The Twilight Zone, Paddy was nevertheless physically fit. Splitting

his time between the Mani peninsula in Greece and Worcestorshire,

England, his last request was to be returned to his native soil.

He died in 2011, aged 96, only one day after his return, the

dearly departed spy in him as spry and sly as ever.

also by John M. Edwards:

Slovenly

Slowdown in Slovakia

Poland:

Potent Potables

Confessions

of a Tasmaniac

The

Bulgarian Way

Sumatra's

Hex & Sex

Kutna

Hora and the Chapel of Bones

Remembering

Bruce Chatwin

Coffe

Art of Sol Bolaños

|

|

|