|

|

don't think twice

BOB DYLAN THE PAINTER

by

ANDREW GRAHAM-DIXON

_______________________________________________

Andrew

Graham-Dixon

is

one of the leading art critics and presenters of arts television

in the English-speaking world. He has presented numerous landmark

series on art for the BBC, including the acclaimed A History

of British Art, Renaissance and Art of Eternity, as well as

numerous individual documentaries on art and artists. For more

than twenty years he has published a weekly column on art, first

in the Independent and, more recently, in the Sunday

Telegraph where this review initially appeared.

He has written a number of acclaimed books, on subjects ranging

from medieval painting and sculpture to the art of the present.

The

Italian Futurists believed modern art should embrace the modern

world, and cursed museums as the dead repositories of a dead

past. They dreamed of firebombing the Uffizi and of razing the

Louvre to the ground. Bob Dylan in the 1960s had his own doubts

about museums too, calling them “cemeteries.” He

believed “paintings should be on the walls of restaurants,

in dime stores, in gas stations, in men’s rooms. . .”

But

museums have a way of absorbing such attacks. They also have

a way of absorbing the work of their fiercest critics as well.

Most of the paintings of the Futurists have ended up in museums.

The manuscripts of Dylan’s own song lyrics will no doubt

wind up there too, and the same fate probably awaits Dylan’s

hitherto little known work as a draughtsman and painter. The

best of it is forthright, sincere, immediate and surprisingly

accomplished. It has the added appeal of being a kind of diary,

kept in images, by one of the most celebrated songwriters and

musicians of modern times. It has already been shown once in

a museum – the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz Museum, in Germany,

to be precise, which staged the first serious exhibition of

Dylan’s work as a fine artist in the winter of 2007. But

museums have a way of absorbing such attacks. They also have

a way of absorbing the work of their fiercest critics as well.

Most of the paintings of the Futurists have ended up in museums.

The manuscripts of Dylan’s own song lyrics will no doubt

wind up there too, and the same fate probably awaits Dylan’s

hitherto little known work as a draughtsman and painter. The

best of it is forthright, sincere, immediate and surprisingly

accomplished. It has the added appeal of being a kind of diary,

kept in images, by one of the most celebrated songwriters and

musicians of modern times. It has already been shown once in

a museum – the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz Museum, in Germany,

to be precise, which staged the first serious exhibition of

Dylan’s work as a fine artist in the winter of 2007.

Yet

the essence of Dylan’s The Drawn Blank Series

is its spirit of resistance to a certain idea of the museum

and what it represents – the idea of becoming, oneself,

a kind of institution, fixed and frozen by illusions of self-importance.

These pictures are the work of someone famous who is emphatically

not buying into his own mummification as genius or guru. That

is implicit in their sheer matter-of-factness, their informality,

their glancing encounters with the stuff of everyday existence.

They are grounded in the ordinary and the mundane and might

almost have been created by the artist in order to remind himself

that, no matter what anyone says, he is (as the Tammy Wynette

song goes) just a man.

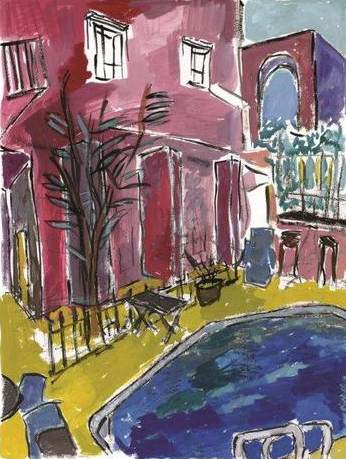

There

is also a shyness, or a profound aloofness – hard to say

which – in the type of looking that made these images.

The Dylan look, characteristically, does not seek eye-to-eye

contact. It is directed restlessly away or sideways, to dwell

on the ordinary things anyone might absent-mindedly fix on –

an arrangement of chairs by a motel pool, a family restaurant

seen from across a street, a house on the top of a hill.  The

ordinariness is much of the point. Dylan draws and paints as

if no one has noticed him. One dream that his pictures might

embody is that of being disregarded. The

ordinariness is much of the point. Dylan draws and paints as

if no one has noticed him. One dream that his pictures might

embody is that of being disregarded.

There

is also an undeniable melancholy about many of the pictures

in The Drawn Blank Series, a sense of rootlessness

and transience. This may have something to do with their origins,

which are a little complex. All of the images have been created

recently, since 2007, but they are without exception based on

templates which Dylan drew in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

During those years, he made a large number of drawings in spare

moments while touring the United States, Mexico, Europe and

Asia. To make The Drawn Blank Series, he had those

drawings scanned on to scaled-up sheets of paper and proceeded

to work them up in a variety of media, including pencil, watercolour

and gouache. Each might be compared to a fresh performance of

an old song; and the series continues to grow. Halcyon Gallery

has extended the number of works first shown at Chemnitz, to

incorporate another 75 originals made exclusively for the exhibition

that coincides with the publication of this book. In these new

pieces, Dylan explores further ways of working with the images.

But no matter how great the transformations of line and colour

in each one, the lineaments of the originals continue to set

the emotional register of the series as a whole.

They

record the disconnectedness of life on tour, a life lived out

of a suitcase, with every day punctuated by the abrupt rhythms

of upheaval from one place and adjustment to somewhere new.

The artist sees boats dancing on the water, beyond the balcony

of his hotel room. He visits the hallway of a baronial castle.

He eats a meal in the restaurant car of a train. He looks down

at a back alley in Chicago. He looks across the street at a

family restaurant. There are no links between the different

things that he sees, except the fact of his seeing them.  One

day he gazes at the bulk of an ancient cathedral, which he paints

as a dark and heavy silhouette, forbiddingly monumental –

all the more so by contrast with the truncated glimpse of a

human leg, perhaps his own, that he includes in this cropped

and snapshot-like composition. The contrast between the solidity

and stability of the church and the artist’s own footloose

existence is implicit. One

day he gazes at the bulk of an ancient cathedral, which he paints

as a dark and heavy silhouette, forbiddingly monumental –

all the more so by contrast with the truncated glimpse of a

human leg, perhaps his own, that he includes in this cropped

and snapshot-like composition. The contrast between the solidity

and stability of the church and the artist’s own footloose

existence is implicit.

The

sequence of pictures includes portraits of people met on the

way – a driver, a pair of sisters, a sturdy woman seen

from the back in an English pub called The Red Lion, a half

naked girl in a room – but there is rarely the sense of

any strong and deep affinity between the artist and his sitters.

Their faces are often mask-like and impassive (although in the

case of one or two portraits of women there is light in the

eyes, and a flicker of affection can be felt). The artist seems

to reserve his truest feelings of identification for unpeopled

views and inanimate objects. His pictures of railroad tracks

seem particularly charged with romantic feeling. The dynamic

perspective of these images, together with their varyingly dramatic

skies, evoke the sense of picaresque adventure long associated

with travel through the wide open spaces of America. The railway

paintings are like pictures of the feelings embodied in the

itinerant folk songwriting traditions of the United States –

the tradition of Woody Guthrie, among others – to which

Dylan has always felt close.

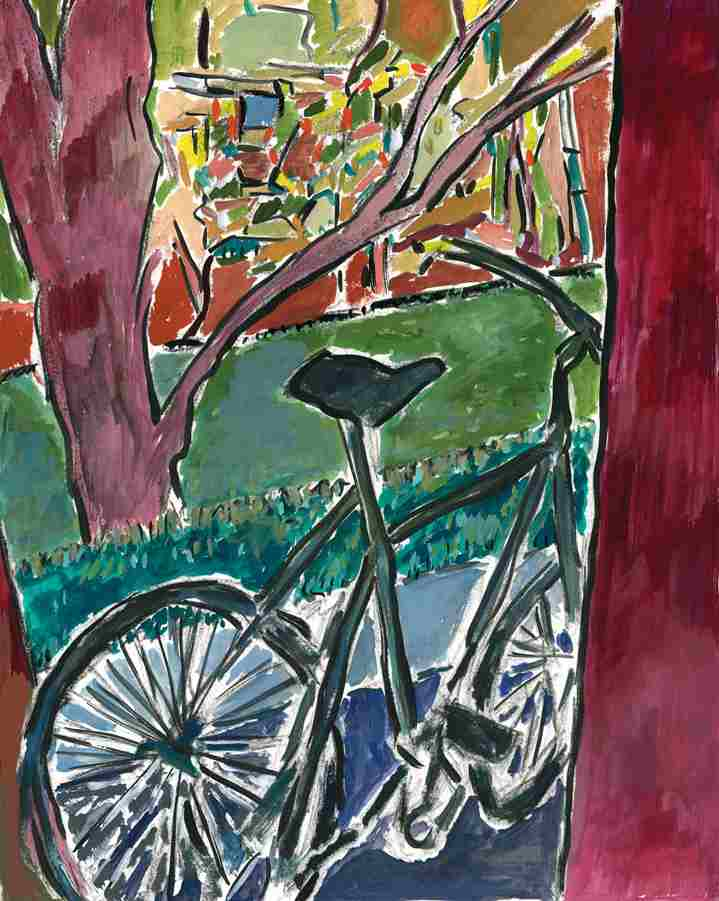

Objects

associated with travelling, with staying on the move, clearly

appeal to him. An old bicycle, propped just so, detains his

attention for quite some while. It fits his eye. He draws it

as if it were the poignant skeleton of an animal encountered

on a country walk.

He

also dwells with particular sympathy on the rickety panels and

bent stovepipe exhaust of an old truck, parked at some kerbside

or other with no one behind the wheel. He revisits the image

several times, colouring it in different ways, enhancing the

beaten-up quality of the bodywork and the uneven layers of retouched

paint.  These

apparitions of a much-travelled vehicle, battered by its passage

through life but still dauntless, prompt the vague suspicion

that these might be disguised self-portraits, of a kind. These

apparitions of a much-travelled vehicle, battered by its passage

through life but still dauntless, prompt the vague suspicion

that these might be disguised self-portraits, of a kind.

Dylan’s

work as draughtsman and painter is unlike that produced by most

occasional artists because it has such a strong look of authenticity.

It is engaging precisely because it is not the fruit of some

misguidedly self-conscious attempt to live up to some ideal

of art. In fact it is a hallmark of his creative activity that

pretty much everything he does to express himself – painting,

writing, singing, presenting a radio show – feels of a

piece with everything else. That is not to say that his pictures

are on the same level as his music. But they are true to their

creator’s sensibility, uncompromised by sentimentality

or ambition – which is why they amount to considerably

more than celebrity memorabilia, the modern equivalent of a

saint’s relics.

There

is plainly no great divide between Dylan the writer and Dylan

the creator of visual images. Chronicles, the first

volume of his autobiography, is a compellingly visual book.

Its prose frequently takes the form of sequences of word paintings,

and Dylan writes in general with an uncanny sense of apparently

total visual recall.

Describing

New York, in the first winter that he spent there, he compiles

a brusque, staccato anthology of quickfire images, each one

like a picture etched in the memory:

Across the way a guy in a leather jacket scooped frost off the

windshield of a snow-packed black Mercury Montclair. Behind

him, a priest in a purple cloak was slipping through the courtyard

of the church on his way to perform some sacred duty. Nearby,

a bareheaded woman in boots tried to manage a laundry bag up

the street. There were a million stories . . . ”

Elsewhere,

remembering his friend Ray’s New York apartment, where

he would sometimes stay, he can summon up the image of a particular

piece of furniture in virtually photographic detail: Elsewhere,

remembering his friend Ray’s New York apartment, where

he would sometimes stay, he can summon up the image of a particular

piece of furniture in virtually photographic detail:

There were about five or six rooms in the apartment. In one

of them was this magnificent rolltop desk, sturdy looking, almost

indestructible – oak wood with secret drawers and a double

sided clock on the mantel, carved nymphs and a medallion of

Minerva – mechanical devices to release hidden drawers,

upper side panels and gilt bronze mounts emblematic of mathematics

and astronomy.

Dylan’s

paintings demonstrate the same strong sense of detail, the same

strong interest in the mood and the specifics of a place as

his prose – and indeed his lyrics, which often turn on

the vivid memory of an unusual object (such as, say, a leopardskin

pillbox hat). The difference is that so many of the things that

he paints and draws in The Drawn Blank Series have

a singularly disenchanted aura about them, a feel of unresisting

and unrewarding blankness – the bland sixties chest-of-drawers

in “Carbondale Motel,” or the switched-off television

set in the shuttered interior of “Lakeside Cabin,”

with its distinctive, old-fashioned, potbellied screen of thick

glass (to give just two of a hundred examples). It is hard,

albeit not entirely impossible, to imagine such objects being

transmuted into the stuff of poetry or song. One of the paradoxes

of Dylan’s art is the fact that while it squarely addresses

the world of everyday things and experiences it also speaks

of reticence and even reclusiveness. It is an art that seems, frequently, to confess its creator’s

inability to engage with the world, for much of the time, at

a more than superficial level. That is the sadness at its centre.

It is an art that seems, frequently, to confess its creator’s

inability to engage with the world, for much of the time, at

a more than superficial level. That is the sadness at its centre.

Dylan

has said that his favourite artists are Donatello, Caravaggio

and Titian – a red-blooded triumvirate, united by their

depth of feeling for life and their virtuoso ability to conjure

illusions of physical and emotional reality. But his actual

style and sensibility seem far closer to the art of late nineteenth-century

France than that of Renaissance Italy. His coiled and slightly

nervous manner of drawing, which often teeters on the brink

of the cartoon or caricature, is in a line of descent that goes

back to the work of artists such as Toulouse-Lautrec, Degas

and Van Gogh – all of whom deliberately played, themselves,

on the borders between the caricature or cartoon and the work

of fine art. In fact, Dylan’s “Man on a Bridge”

might almost be a pastiche of a Van Gogh drawing; the figure

even has something of a Van Gogh look about him.

It

is not particularly surprising that Dylan’s art should

have its most obvious debts there. The Parisian painters of

the late nineteenth century were inspired by a particular ideal

of modern, urban realism that was to have an enormous influence

on the whole world of the arts – music, dance, literature,

poetry and music, as well as painting. Their ambition to be

“painters of modern life,” to catch the teeming

and multitudinous spirit of “modernity” itself,

to celebrate the lives of whores and courtesans and dockworkers

as well as the lives of the careless rich, would reverberate

through the culture of the twentieth century. An American painter

such as Edward Hopper was heir to the ideals of realism forged

in the aesthetic workshop of nineteenth-century  Paris.

The same holds true for an author such as Jack Kerouac, whose

On the Road applies the principles of modernist realism

to the theme of an American odyssey. And it holds true too –

in spades – for the young Bob Dylan, songwriter and poet-musician

of the multiplicity of lives around him. So it makes perfect

sense that, as a painter and draughtsman, he should hark back

to the early modernist tradition that was always a kind of spiritual

home for him in the first place. But it also needs to be said

that what is going on, in The Drawn Blank Series, is

a little more complicated than just a harking back. Paris.

The same holds true for an author such as Jack Kerouac, whose

On the Road applies the principles of modernist realism

to the theme of an American odyssey. And it holds true too –

in spades – for the young Bob Dylan, songwriter and poet-musician

of the multiplicity of lives around him. So it makes perfect

sense that, as a painter and draughtsman, he should hark back

to the early modernist tradition that was always a kind of spiritual

home for him in the first place. But it also needs to be said

that what is going on, in The Drawn Blank Series, is

a little more complicated than just a harking back.

The

aesthetic ideals of classic early modernism were most eloquently

enshrined in Charles Baudelaire’s essay, “The Painter

of Modern Life.” In a celebrated, virtuoso passage of

writing, Baudelaire personifies the ideal modern artist’s

creative and open approach to the chaos of modern life in the

figure of the flaneur – one who wanders the city’s

streets and boulevards, immersing himself in the sights and

sounds and above all the infinitude of lives that surround him

there:

The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water

of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one

flesh with the crowd. For the perfect flaneur, for

the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house

in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement,

in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite. To be away from

home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the

world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden

from the world – such are a few of the slightest pleasures

of those independent, passionate, impartial natures which the

tongue can but clumsily define. The spectator is a prince who

everywhere rejoices in his incognito... Thus the lover of universal

life enters into the crowd as though it were an immense reservoir

of electrical energy. Or we might liken him to a mirror as vast

as as the crowd itself; or to a kaleidoscope gifted with consciousness,

responding to each one of its movements and reproducing the

multiplicity of life and the flickering grace of all the elements

of life. He is an ‘I’ with an insatiable appetite

for the ‘non-I’, at every instant rendering it and

explaining it in pictures more living than life itself . . .

”

Change

the word “pictures” to “songs,” in that

last sentence, and you have a near-perfect description of the

young Bob Dylan as songwriter – his sensibility, his methodology,

his kaleidoscopic (and ventriloquistic) gift of reflection.

Dylan’s own autobiography, Chronicles, is a nearly

uncanny confirmation of his Baudelairean heritage. It is a book

that recounts, on page after page, his picaresque progress through

life as a modern, American version of the flaneur,

a man immersed in the world but almost invisible to those around

him, gathering the materials for his art from the teeming lives

of the city – guys in leather coats, priests in purple

cloaks, women struggling with their laundry, “a million

stories” on all sides.

But

something happened to compromise Dylan’s sense of engagement

with the world, something that struck home to him in about the

mid-1980s – not long, in fact, before he did the drawings

that form the basis of The Drawn Blank Series. The

realization had been gradually dawning in him that his own celebrity

had cut him off from the very subject matter – raw and

actual life, in the immediacy of its unfolding – that

was the wellspring of his imagination. He described the process

in an interview rather grudgingly given to a documentary-maker

named Christopher Sykes, for a film transmitted in the BBC’s

Arena strand in the autumn of 1987. As Sykes attempted

to elicit answers from him, Dylan simply drew a portrait of

his would-be interviewer, refusing to respond with more than

a monosyllabic response. But in the end he opened up for a few

brief seconds. His theme was fame and why, for an artist such

as him, it was a kind of curse. “It’s like when

you look through a window – say you’re passing a

little pub or inn – and you see all the people eating

and drinking and carrying on. You can watch outside the window,

and you can see them all being very real with each other, as

real as they are going to be. Because when you walk into the

room, it’s over, you won’t see them being real any

more . . . ”

That

sense of being on the outside of life – a life that will

change and become artificial as soon as you walk in –

is everywhere in the images of The Drawn Blank Series.

It is there in the deliberate solitariness implied by so many

of the pictures, documenting as they do an existence spent holed

up in hotel rooms or other places of refuge. It is there in

their frequently unsettling, liminal perspectives – threshold

perspectives, which suggest the point of view of someone hovering

on the point of going into a place but never quite going through

with the intention. A house is seen from across the street,

a tenement building is viewed from the fire escape side, a street

is viewed, through the railings of a balcony, and from above.

One

writer responded to the first exhibition of pictures from The

Drawn Blank Series, at the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz Museum

by remarking that nearly all of the paintings exhibit what in

German is known as schwellenangst – the fear

of entering a place. It was a perceptive comment. Dylan does

have a constant habit of framing images through doors or windows

or passageways, from the half-seclusion of balconies or verandas

– or to be strictly accurate that is what Dylan did, some

twenty years ago, when he originally composed these images,

which seem in so many ways like the visual expression of the

consuming melancholy so evident in his remarks about how he

felt, those days. The truth is that the pictures in The

Drawn Blank Series are palimpsests, or memories revisited

at a distance and altered in the process. In many cases he has

cheered up his original drawings in the act of reworking them

– adding little touches of humour or anecdotal detail,

or enlivening them with bright colour schemes that seem to evoke

the decorative compositions of an artist such as Raoul Dufy.

Dylan is no longer the melancholic that he was, back in the

1980s, when he began The Drawn Blank Series But in

the end there is no concealing the essential melancholy that

is written into almost every one of its compositions. These

pictures are the lament of a flaneur who can no longer

plunge into life in the way that he used to. They are the sad

song of a spectator-prince who has lost his incognito.

Note: Graphics added (and cropped from white background) to

original article.

Republished according to Creative

Commons Act.

|

|

|