|

|

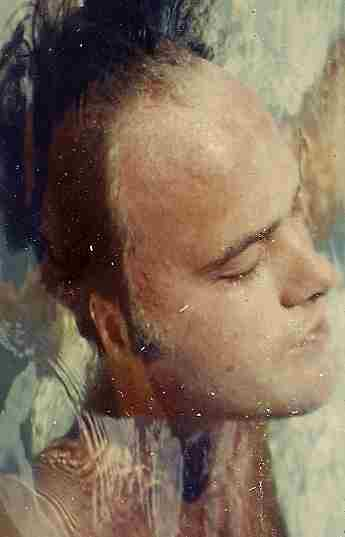

the return of the late

BRUCE CHATWIN

by

JOHN M. EDWARDS

_____________________________________

John M. Edwards middlenamed his daughter after his favourite

travel writer, Bruce Chatwin. His work has appeared in Amazon.com,

CNN Traveller, Missouri Review, Salon.com, Grand Tour, Michigan

Quarterly Review, Escape, Global Travel Review, Condé

Nast Traveler, International Living, Emerging Markets and

Entertainment Weekly. He helped write “Plush”

(the opening chords), voted The Best Song of the 20th Century

by Rolling Stone Magazine.

John M. Edwards middlenamed his daughter after his favourite

travel writer, Bruce Chatwin. His work has appeared in Amazon.com,

CNN Traveller, Missouri Review, Salon.com, Grand Tour, Michigan

Quarterly Review, Escape, Global Travel Review, Condé

Nast Traveler, International Living, Emerging Markets and

Entertainment Weekly. He helped write “Plush”

(the opening chords), voted The Best Song of the 20th Century

by Rolling Stone Magazine.

For

the late great Bruce Chatwin (1940-89) life was a journey to

be taken on two legs. Obsessed with nomads, he periodically

became one himself, ditching two successful careers, as Sotheby’s

art expert and Sunday Times columnist, to roam the

exotic edges of the literary wilderness.

Whether

it was stumbling across the Sudanese desert with Kipling’s

migratory tribes of Fuzzy-Wuzzies, following in the footsteps

of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid across the Patagonian

pampas, or tracing mythic Aboriginal songlines in the Australian

outback, the enigmatic wanderer was always in search of the

marvelous, extraordinary, and unexpected, even if he didn’t

exactly rough it. (His silk jammies were usually within snatching

distance).

So

what if he was also notorious for bending the truth a little?

Chatwin’s

alchemical fusion of fact and fiction is brought to the fore,

for example, in Susannah Clapp’s entertaining biography,

With Chatwin: Portrait of a Writer. Chatwin’s

former editor paints a vivid portrait of the multifaceted, irrepressible,

dervish-like walker and talker she knew. Clapp says, “Chatwin

liked clear outlines, plain surfaces and unexpected bursts of

color.” He also was intrigued by “paradox and inconsistency.”

Though the book is clear on what Chatwin liked, it leaves what

he was like somewhat uncertain. There is a disputed border between

biography and biographer, since Clapp’s blue pencil pared

down the lapidary Impressionistic prose -- with its honed Hemingwayesque

phrases and profound Proustian details -- that made Chatwin’s

literary reputation.

Examining

the editing process itself, Clapp explains how they reduced

the once-massive manuscript of In Patagonia, a classic

that paradoxically broadened the field of travel writing, down

into a slim volume of cubist pen-portraits. Dangling between

fact and fiction, mixing myth, history, reportage and autobiography,

Bruce pops up all over Patagonia, but dispenses with important

(boring to Chatwin) links like how he got from A to B or his

secret thoughts while on the road, as his friend and energetic

rival Paul Theroux frequently complained. Intricately linked

to Chatwin personally and professionally, Clapp is well suited

to connect the dots while separating the man from the books,

the art from the life, the legend from the reality.

By

eyeballing his oeuvre, we can further deconstruct some of the

myths surrounding a man who eventually became famous for being

famous. As Michael Ignatieff famously quipped, Chatwin’s

own character “was one of his greatest inventions.”

In

fact, while I attended Tulane University in New Orleans, I got

to know Bruce a little when the much-older-than-we pretend student

crashed an anthropology class I was taking, with a prof sporting

an antique square mustache similar to the one worn by Charlie

Chaplain as The Little Tramp or an infamous totalitarian

dictator. I also was there the night Bruce famously danced with

a live python around his neck. I remember saying to him, “Bruce,

what are you doing? That snake might be poisonous.” With

pretend fear, he backed slowly out of the bar, and went onward.

Before

departing Planet Earth in 1989 (at age 48) of what he claimed

was a “rare bone disease” caused by Chinese eggs

(close sources say it really was AIDS), Chatwin had become a

living literary cult figure, comparable with such figures as

Oscar Wilde, Robert Louis Stevenson, and T. E. Lawrence. Still,

Chatwin known to his friends as ‘Chatterbox,’ was

“feted for his looks as well as his books” -- indeed,

he was celebrated for his extraordinary physical beauty as well

as his gifts as a conversationalist and writer. With his Midas

locks, patrician profile and extraterrestrial blue eyes, he

would, according to Howard Hodgkin, “flirt with man, woman,

or dog.”

One

acquaintance said memorably that he had the “mad mad eyes

of a nineteenth-century explorer,” others, the “glittering

eyes of the Ancient Mariner.” Since I’m sure I met

him years ago in New Orleans, without knowing exactly who he

was (some blond guy named Bruce with a live python around his

neck), I would imagine that he paid close attention to his appearance,

constantly grooming himself and checking his reflection. On

the trail, in Afghanistan, Wales, or India, he could be found

in his signature khaki shorts (“Bruce’s little shorts,”

joked his good-time-charlie friends) -- which I imagine he might

have modeled after Tintin -- with ankle-length walking boots

and neatly turned-down fawn socks, delighting observers with

its whiff of the Raj.

Salman

Rushdie said the Chatwin in the books was not “the whole

person he was when you met him.” Aesthete, archaeologist,

art expert, journalist, gourmand, photographer, writer, the

polymath Chatwin even as a child seemed to have “a sense

of his own importance,” according to Clapp. Maybe, a kind

of ESP of the Bruces he’d later be.

Born

on May 13, 1940, in Sheffield, England, Chatwin’s early

years were marked by movement. “I lived in NAAFI canteens

and was passed around like a tea urn,” he remarked on

his semi-nomadic childhood. Even at Marlborough ‘college’

(transatlantic translation: high school), Bruce was unlike other

students. Nicknamed “Lord Chatwin,” he was “an

Edith Sitwell reader among a lot of Nevil Shute fans,”

began collecting expensive antique furniture, and was singled

out for his abilities as an actor, as well as his insouciance.

One teacher wrote of him, “His gift may be slender perhaps,

but it is genuine.” But not genuine enough to get him

into Oxford or Cambridge. It wasn’t until Bruce began

working at Sotheby’s that he came into his own.

Much

is made about Chatwin having The Eye, the quasi-mystical ability

to recognize at a glance an original or a fake. For example,

as a teen star at Sotheby’s “the blond boy”

correctly identified a Picasso harlequin as a forgery. Similarly,

when he began his writing career at the late age of 37, he could

distinguish between a fine or foul sentence. Or between interesting

and boring. “Bruce made people look at things differently

and made them look at different things,” Clapp quips.

In

one of my favorite miniatures from What Am I Doing Here

(which famously doesn’t explain what he was doing there,

nor does it evidence good punctuation, since the question mark

in the title is inexplicably missing), Chatwin describes a memorable

(but iffy) Art World meeting with The Bey:

One morning there appeared an elderly and anachronistic gentleman

in a black Astrakhan-collared coat, carrying a black silver-tipped

cane. His syrupy eyes and brushed-up moustache announced him

as a relic of the Ottoman Empire.

“Can you show me something beautiful?” he asked.

“Greek, not Roman!”

“I think I can, “ I said.

I showed him a fragment of an Attic white-ground lekythos by

the Achilles Painter which had the most refined drawing, in

golden-sepia, of a naked boy. It had come from the collection

of Lord Elgin.

“Ha!” said the gentleman. “I see you have

The Eye. I too have The Eye. We shall be friends.”

He handed me his card. I watched the black coat recede into

the gallery:

Paul A_____ F_____ Bey

Grand Chamberlain du Cour du Roi des Albanis

Fact

or fiction? Fact. Bruce really did own Hawaiian King Kamehameha’s

bed sheet. Fiction? Was Bruce really approached, as he claimed,

by British Intelligence while traveling in communist Eastern

Europe? Fact. Bruce sort of smuggled a Cezanne out of France.

Fiction? He tricked Customs inspectors by posing as the picture’s

painter. Fact. Bruce really was caught in a coup in Benin, while

researching The Viceroy of Ouidah. Fiction? What happened to

him in the story “The Coup” (atrocities are spoken

of in the accents of Noel Coward) is apocryphal.

Stories

simply changed as they were recalled, becoming in translation

akin to tales both tall and twice-told. He often talked -- sometimes

as if it were fantasy, sometimes fact -- of a day spent at Carnival

in Rio, making love first to a girl, then to a boy. To Chatwin,

the word story was meant to “alert the reader to the fact

that, however closely the narrative may fit the facts, the fictional

process has been at work.” This was taken to the extreme

in The Songlines, when Chatwin appears as a fictional

character named ‘Bruce’ knocking about the dreaming

tracks of the Aussie outback with a guy called Arkady (who might

have really been Salman Rushdie).

Over

the causes of wanderlust, Chatwin puzzled. In much of his work,

he attempts to explain why men wander rather than sit still.

(Even his surname, derived from the Anglo-Saxon chette-wynde,

meaning winding path, fortuitously prefigures his major obsession).

He agreed with Pascal that man’s unhappiness stems from

a single cause: “his inability to remain quietly in a

room.”

Hence,

in Bruce’s anti-travel novel On the Black Hill,

two identical octogenarian twins never leave their house of

birth in the Welsh countryside. In The Viceroy of Ouidah,

a crammed and claustrophobic book, the main character, a Brazilian

slave trader from Dahomey, considers “any set of four

walls to be a tomb or a trap,” yet is involved with confining

others. Conversely, The Songlines is airy and open,

examining mankind’s migratory drive to walk long distances.

Chatwin, like Baudelaire, had a “horreur du domicile,”

and was often away from his immaculately planned London pied

à terre (“a cross between a cell and a ship’s

cabin”), constantly looking for the ideal space in which

to write, seemingly always elusively elsewhere.

The

opposite of the nomad is the collector, and Chatwin even talked

about his travels as collecting places. In his later years,

Chatwin, once an expert on the Impressionists and an avid art

collector himself, developed an almost Bedouin sensibility.

Sharing the nomad’s horror of the graven image, he believed,

“Man should own no possessions but those he can conveniently

carry.”

Which

strikes home to me, since I laboured under a heavy backpack

for one entire year in the Antipodes (Australia, New Zealand,

and the South Pacific) and two full years in Europe. Where,

believe it or not, I bumped into Bruce again -- many years after

our drunken binges at the New Orleans watering holes of The

Boot and Tin Lizzies -- at a mountain hut along New Zealand’s

dire Routebourne Track, where he drank most of my whiskey and

said, “Be sure to write it all down: beyond your wildest

dreams.” He cast a spell that seemingly echoed down through

the years.

And

when I returned to United States, my dad showed me his copy

of the then recently released The Songlines, with a

photo of Bruce on the back, resembling Ilya Kuriakan from “The

Man From Uncle.” I then decided, like Barton Fink, to

also become “A Writah.”

When

Chatwin finally got around to throwing out most of his own possessions,

only his close friends knew what he was getting at in so many

words: Smash the idols. While collecting art and freely giving

it away, Chatwin developed very pronounced theories about the

cult of fetishism and the decadence of possession -- a subject

he would explore in essays like “The Morality of Things”

and return to in his last book, Utz, about an obsessive-compulsive

collector of Meissen porcelain in Prague. In one passage the

nameless narrator (Bruce?) tells Utz of a man he met who was

a dealer in dwarfs:

“And what

did they do with those dwarfs?” Utz tapped me on the knee.

He had paled with excitement and was mopping the sweat from

his brow.

“Kept them,” I said. “The sheik, if I remember

right, liked to sit his favorite dwarf on his forearm and his

favorite falcon on the dwarf’s forearm.”

“Nothing else?”

“How can one know?”

“You are right,” said Utz. “There are things

one cannot know.”

One

thing nobody can know for sure is what Chatwin, with his museum-like

mind and ultra-ambiguous persona, was really like below the

surface. It was one of his charms, Clapp claims, to be “several

apparently contradictory things and to reconcile them in his

books.” A literary chameleon, Chatwin, who’d purportedly

“never heard of the Muppets,” was famous for his

evasiveness. (“I don’t believe in coming clean,”

he once said -- no: creeched -- to Paul Theroux.) Yes indeed,

he was full of contradictions: he was a lover of the austere

who had a flamboyant manner; he was gay, yet happily married;

he worked in the art world, but railed against objects and possessions;

he proposed the Nomadic Alternative for mankind (his

unfinished magnum opus), while staying and writing abroad comfortably

ensconced in the homes of famous friends. (“For a nomad,”

commented one host after an extended Bruce visit, “he

spends an awful lot of time in one place.”) Even his most

commercially successful book, The Songlines, is an

anomaly -- its publishers classified it nonfiction in Britain

but fiction in America.

Yet

after reading every single last one of his essays in the posthumously

released Anatomy of Restlessness, I decided that Bruce, so difficult

to pin down and pigeonhole, simply wanted to be a writer, on

the strength of one line: “I thought that telling stories

was the only conceivable occupation for a superfluous person

such as myself.”

Going

back to Clapp, rather than to Nicholas Shakespeare and his amazing

definitive biography (which you will have to judge for yourself),

she quite elegantly suggests in a roundabout way that Bruce

might have wanted to be an actor on the world stage. She calls

him “a skillful manager of remarkable entrances and surprise

appearances,” and one does wonder if Chatwin did in fact

live life as if he were in a very weird version of The Truman

Show -- waiting the mixed reviews of his audience.

His

absences were as dramatic as his presences. After a hysterical

bout of blindness (entirely psychosomatic), he exited Sotheby’s

by setting off for the Sudan, under doctor’s orders to

gaze at long horizons; the symptoms mysteriously disappeared

at the airport. His restless nature outed again when the wily

wanderer resigned from the Sunday Times with a theatrical

telegram, simply saying, “Gone to Patagonia.”

Toward

the end of his life, intermittently feverish and high on painkillers,

Bruce reappeared in public as “hyper-Bruce, an exaggerated,

speeded-up version of his already emphatic self.” Basically,

he would just show up like an unexpected surprise party favour

at shindigs, lavishly entertain guests at the Ritz, or wheelchair

around on manic buying-and-selling expeditions, announcing to

store owners, “I’m going to be one of your best

customers” -- while his wife, Elizabeth, and a loyal cadre

of friends and fans busily canceled his checks and returned

objects to dealers. Even during his grim finale, groomed in

bed “like an old baboon” by his wife (and nurse),

he did what he did best: Chatwin chatted.

In

one final Chatwinesque twist, life imitated art. Chatwin’s

commemoration service was a baffling, even camp, Greek Orthodox

ceremony, complete with black-robed and bearded priests swinging

censers and chanting Bruce (his last joke, according to friend

Martin Amis). Which occurred the same day as the Ayatollah’s

fatwa on Salman Rushdie, who appeared to pay his respects before

being whisked away into hiding. Clapp, whose own prose style

at times weirdly mirrors Chatwin’s sparse, exotic signatory

script) says it was as if Bruce had “manipulated”

the scene from beyond the grave.

Though

Chatwin “hardly wrote a confessional line in his life”

(he never publicized his homosexuality, or, better, bisexuality,

for example), only time will tell what other surprises await

inside his eighty-five private moleskin notebooks, scheduled

to be released to the public sometime around 2013/2014. But

meanwhile we have Chatwin’s published work to puzzle over,

urging even the most sedentary armchair readers into the unknown

and awakening the nomad in all of us.

And

I’m not joking when I say that I believe Chatwin is still

alive somewhere. Or, as I’m wont to aphorize: “Some

of us will live forever. . . .” In a vainglorious attempt

to retrace Chatwin’s past and path, I made a special request

to stay a few nights in his atmospheric room at the Ritz Hotel

in “Londinium,” which was homely enough, like a

flowery combo of your batty aunt’s and Van Gogh’s

bedroom. Dealing with the staff, I felt like a defensive cultish

member of The Psychic Friends Network: “No, I’m

not John Edward, the televangelist psychic; I’m John Edwards

(with an ‘s’), the traveling journalist.”

Bruce

Chatwin’s fairly recent collection of letters called Under

the Sun is a window into the real guy behind the myth. With

so many secrets to keep, Bruce would deem this collection of

his solitary epistles as an outright invasion of his privacy,

which is reason enough to chuck it into your Amazon cart and

then chart a course for high adventure.

also by John M. Edwards:

Coffe

Art of Sol Bolaños

|

|

|