As a 5-year-old

I was given a clarinet to study and I started to play. One

of the unspoken platitudes when the word ‘talent’

comes up is the learning curve development -- how long will

it take for junior to reach a respectable level of proficiency?

Most would agree that a novice youngster with real talent

will show it within six months. That was the situation in

my case and I soon got used to my grammar school teachers

oohing and aahing about my musical promise at school concert

time. They practically ordered me to audition for Gotham’s

leading conservatories and I managed acceptance at all of

them. So Saturdays I took my clarinet, packed a lunch and

subwayed to attend classes. All of the study involved classical

music and very soon I began enjoying Bach, Mozart, Schumann

etc. and other legends who wrote clarinet pieces.

One day

I began practicing a Von Weber clarinet piece and my teacher

told me to listen to what he thought was the definitive

performance of it by Benny Goodman. I was almost seven when

I heard Goodman’s recording and at the same time discovered

his jazz credentials. I instantly became hooked on Goodman’s

small group recordings (sextets, quartets) and played “’Rachel's

Dream” so often on the phonograph that

my mom began groaning. But the “King of Swing”

had indeed swung me over to jazz. It was the improvisation

challenge

that attracted me the most and his improvisational lines

at breakneck tempos wowed me. Nevertheless it wasn’t

until I was about nine when I discovered other jazz and

became an apostle of bop.

challenge

that attracted me the most and his improvisational lines

at breakneck tempos wowed me. Nevertheless it wasn’t

until I was about nine when I discovered other jazz and

became an apostle of bop.

My relationship

to music took several turns. I continued to perform through

college and later became a jazz writer, producer, historian

and professor of this music and constantly met jazz luminaries

in interview sessions, rehearsals and seminars. Once, during

the early 60s the management of Basin Street East invited

me one night to come in and review Benny Goodman and Peggy

Lee. Goodman was at the height of his career and Lee astounded

with her beauty and lyrical genius. I interviewed Goodman

backstage after the show and discovered through his anecdotes

insights into his creative proclivities which I included

in the write-up. The master had by this time conquered movie

audiences (appearing in feel good films with Judy Garland,

Esther Williams, Van Johnson) and had nations listening

to his radio broadcasts. His legendary Carnegie Hall concert

of 1938 was instrumental in legitimizing jazz.

During

the next decade I produced a lot of big band jazz concerts:

Lionel Hampton, Buddy Rich, Woody Herman, Dave Brubeck,

Maynard Ferguson, Stan Kenton, Dizzy Gillespie, Count Basie

and countless vocalists. And if I was only rarely able to

turn a small profit, the aesthetics more than compensated.

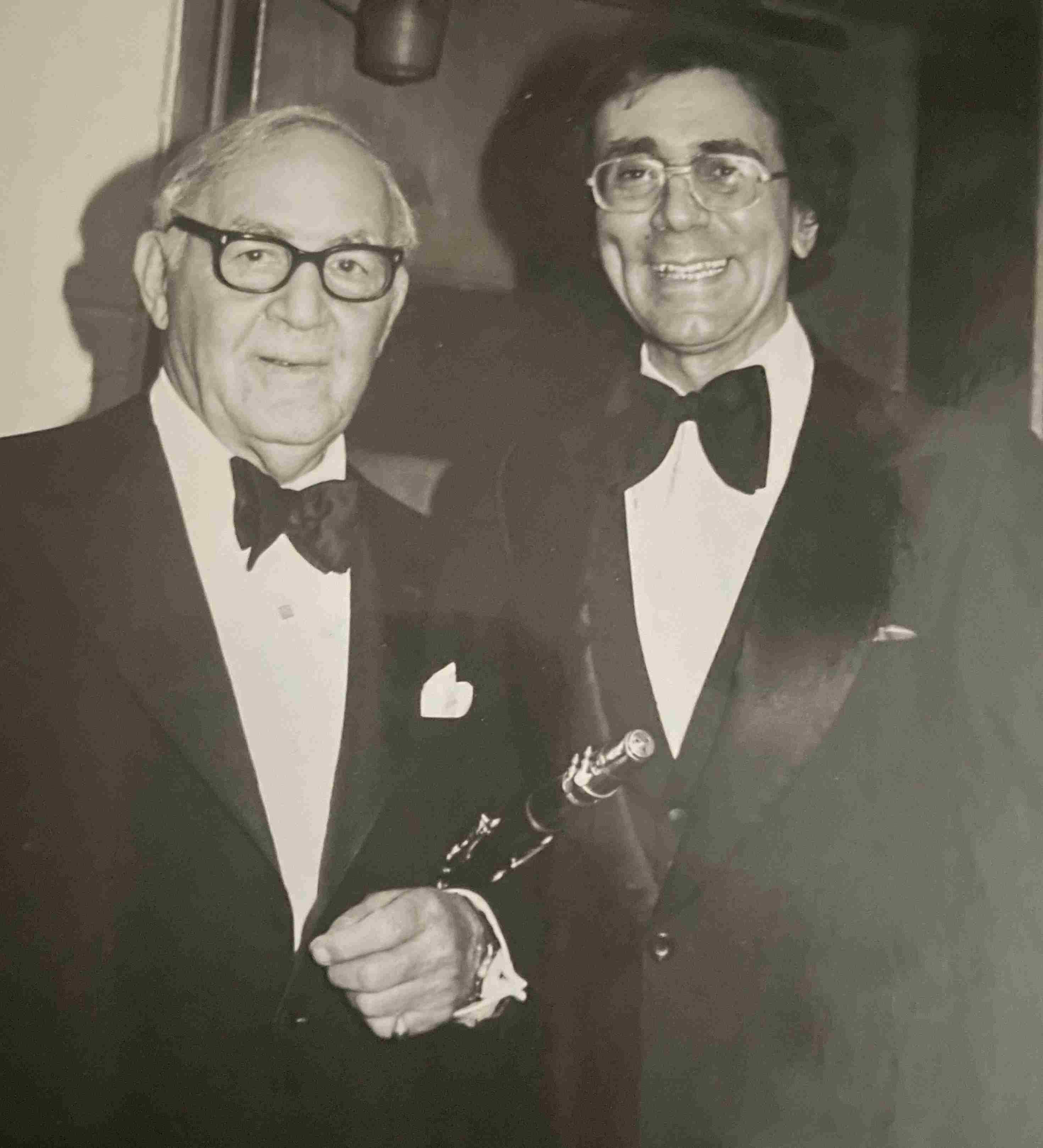

Then one

day I succeeded in convincing Benny Goodman to star in one

of my shows. He hadn’t performed in New York for several

years and I knew sales would be brisk. We sold out two shows

in a 2500 seat theater venue in one afternoon. I was very

excited.

When Goodman

said ‘yes’ it was on the condition that I put

the band together, and that I had to book the very best

players of the day. Thank goodness I had Bucky Pizzarelli

as a good friend to help me as well as play in the group.

And so we succeeded in getting star musicians such as drummer

Mel Lewis, hornmen Scott Hamilton and Warren Vache, pianist

John Bunch, and bassist Phil Flanigan. All had performed

with Goodman for years so we knew he would be happy with

the sidemen.

I began

visiting Benny at his east side apartment to arrange the

myriad details for the concert. I was amazed to discover

that each time I got off the elevator I could hear him practicing.

It was toward the end of his career but his musical dedication

hadn’t waned and I sat there transfixed watching him

run through multi-noted exercises with wild improvisational

sequences.

When it

came time for the ‘dress’ rehearsal, I prepared

carefully not chancing rebuke from the leader. At considerable

expense I rented space at the Carlyle hotel because it was

close to Benny’s apartment. On a cold day in March,

I brought him to rehearsal and had an astounding experience.

The band members greeted him with the usual jocularity that

occurs on a bandstand. Musicians are always telling amusing

stories usually having to do with some incident that happened

either on their endless touring buses or on performance

stage somewhere.

As

Benny removed his horn from the case he returned the friendly

greetings from the guys but there was a measure of detachment

in his demeanor. I instantly recalled the stories about

his strict control of his orchestra and limiting his fraternizing

with the sidemen. The band members also took in his comments

and rather quickly sat down, picked up their horns and sat

up in rapt attention. The atmosphere was one of a platoon

standing at attention waiting for orders.

As

Benny removed his horn from the case he returned the friendly

greetings from the guys but there was a measure of detachment

in his demeanor. I instantly recalled the stories about

his strict control of his orchestra and limiting his fraternizing

with the sidemen. The band members also took in his comments

and rather quickly sat down, picked up their horns and sat

up in rapt attention. The atmosphere was one of a platoon

standing at attention waiting for orders.

At my

Carlyle rehearsal Goodman ran up and down the scales executing

some clever interludes. And then it happened.

He finished

a sequence and instantly segued into first bar melody of

“Avalon” - a tune he had long performed. And

at the end of the measure the rest of the band was right

there at the pick up and all were off at a blistering tempo

. . . I couldn’t believe it . . . the band was roaring

and Goodman had not informed them of what tune he had selected...

Incredulously,

I accosted Bunch later on with the obvious question: “How

the hell did you guys know what tune he was going to play”?

He looked at me disdainfully and simply said, “This

is a Benny Goodman rehearsal . . . if you’re not ready

for the opening hit you won’t be playing at the next

show.”