Tammy Ruggles

is a legally blind photographer, artist, and writer who lives

in Kentucky. Her work can be found in many publications, and

prints can be found in her online

portfolio.

As a legally blind

person, choosing to pursue photography may seem like an unlikely

if not impossible choice.

But

I haven’t always been legally blind. There was a time

I could read print books, drive a car and see where to stop

pouring water in a glass.

But

I haven’t always been legally blind. There was a time

I could read print books, drive a car and see where to stop

pouring water in a glass.

I was born with a progressive blinding disease known as RP,

which slowly robs the vision over time. My first pair of glasses

was at the age of two, but it took years to become legally blind.

I enjoyed books,

writing and art from an early age. At 12 I started to write

short stories and poems, and I sketched portraits and animals

with a pencil. Among these interests was photography. If there

was a camera around, I wanted to pick it up and use it.

When I reached my teenage and college years, I wanted to pursue

photography in a more serious way, in a classroom setting, but

couldn’t, because with RP comes night blindness, and I

couldn’t see in a darkroom to mix chemicals or develop

photos, nor could I read settings on a camera to shoot manually.

Ansel Adams and Alfred Stieglitz were two great photographers

I admired, and I wanted to make pictures like theirs. Ansel’s

because his main focus was landscapes, and Alfred’s because

of the painterly quality.

But this dream couldn’t be. I had to set serious photography

aside and be satisfied with taking family snapshots on instant

cameras.

Don’t get me wrong. I loved taking pictures of my family,

but it wasn’t the fine art photography I desired deep

down.

Photography was art to me, just as writing and sketching were.

I took four years of high school art, and two or three more

in college, all the while earning a degree in social work, and

another in adult  education

and counseling.

education

and counseling.

During these years and the ones to follow, my vision deteriorated,

to the point of being declared legally blind at age forty.

RP took my social work position, but gave me a second career

as a writer. It took my skill as a sketcher, but gave me the

ability to finger paint.

I was very happy with my career as a part-time writer, and had

put photography to bed, until 2013, when I kept hearing about

how easy it was to use point-and-shoot digital cameras.

The desire for fine art photography came calling again, but

I had my doubts. One, what would people think, and two, would

I make a fool of myself by trying? Whoever heard of a legally

blind photographer? I had kept my white cane hidden in a corner

for ten years because I felt uncomfortable about it. How would

it feel for people to see that I was trying to be a serious

photographer? And could I even do it? My world was extremely

blurry now. Could my remaining vision make sense of my pictures?

After some self-talk to raise courage, I finally took the step

needed, and ordered a camera.

At first it sat untouched. I still had doubts about doing it,

but the yearning to try photography was so strong I had to.

Once my son said how easy it was and that I should try it, I

did just that.

And once I had photos to view on my 47-inch computer screen,

it was sealed. I wanted to pursue it with everything I had.

I can only liken it to someone who is deaf being able to hear

with a hearing aid, or a paralyzed person being able to get

up out of a wheelchair and walk again.

Not only could I take interesting or pretty pictures in the

fine art way I’d always wanted, I could actually ‘see’

things around me that I hadn’t seen in many years, like

faces, flowers and objects. This is because my big screen makes

everything, well, big. Two feet tall, and even taller if I want

to zoom in closer.

In a way, photography opened up a visual window in a way that

hadn’t even occurred to me.

I don’t know how long this window will remain open. My

vision gets worse with time, and it gets harder to see. This

is why I’m going to enjoy photography, this way, while

I can.

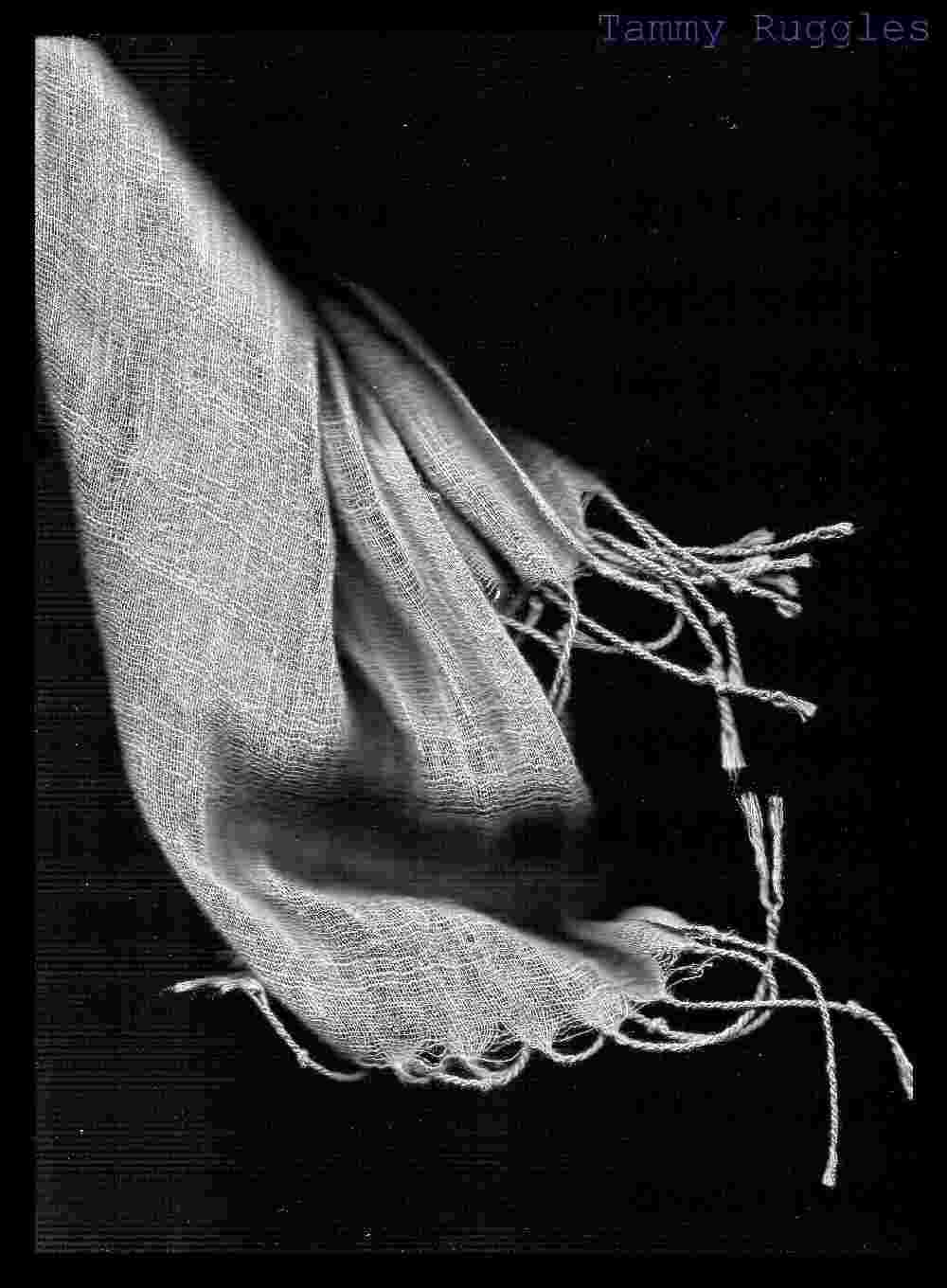

Because of RP, I see best in high contrast, and this is why

I work in mostly black and white. I love color, but colours

are harder for me to distinguish. With black and white, I can

make out the shapes more clearly. Sometimes I add more contrast

just to see it better.

Not

all of my photos are ‘good’ to me. I discard many

more than I keep. I want others to enjoy them, and it’s

interesting when viewers describe things in my photos that I

can’t, or see my photos in a way that I don’t.

Not

all of my photos are ‘good’ to me. I discard many

more than I keep. I want others to enjoy them, and it’s

interesting when viewers describe things in my photos that I

can’t, or see my photos in a way that I don’t.

That’s part of the appeal of photography for me -- -the

dialogue between me and the viewer.

The fact that I’m practicing photography at all is amazing,

even to me. I’m enjoying every minute of it. There is

no mystery or trickery involved. I just use the vision I have

left, plus an easy camera, and my large monitor.

I’m legally blind, which is not the same as completely

blind, and I think it’s important to make that distinction.

My world isn’t dark. It’s blurry. Turn a camera

lens far out of focus and you will see.

I can’t say just why I was drawn to photography as a young

person, besides the fact that I felt it was an art form that

I thought I would enjoy. But I can say that it satisfies my

artistic nature. In a way, it’s painting pictures, but

with a camera. Sometimes, in a sense, I choose pictures that

I would sketch or paint if I could. Most of my process occurs

after I’ve snapped the shutter, when I choose which photos

to delete, and which photos to keep.