Nick

Catalano is a TV writer/producer and Professor of Literature

and Music at Pace University. He reviews books and music

for several journals and is the author of Clifford

Brown: The Life and Art of the Legendary Jazz Trumpeter,

New

York Nights: Performing, Producing and Writing in Gotham

, A

New Yorker at Sea,, Tales

of a Hamptons Sailor and his most recent book,

Scribble

from the Apple. For Nick's reviews, visit his

website: www.nickcatalano.net.

Many times during

the 25 year period of my producing the Standup Comedy shows

described in the last issue of Arts

& Opinion, the question of whether this

hugely popular entertainment rose to the level of an art

form came up often. Addressing this question in a short

essay is a formidable task but a historical survey of comedy

can be helpful.

In Ancient

Greece, Aristophanes looms as the giant figure at the onset

of comic creativity. Even a quick reading of his play Lysistrata

reveals the scope of his comic genius. For the first time

in history we see Farce ( the scene with Myrrhine seducing

Kinesias is hysterical) and Satire (women using sex to oppose

the Peloponnesian war) as the two principal elements of

early comedy. Aristophanes of course utilizes these elements

in all of his plays and they are such powerful producers

of laughter that they become the essential weaponry of comedy

through the ages. Roman  writers

Plautus and Terence are quick to adopt this successful formula

as they add versification, disguise, mistaken identity,

situational irony and other techniques to further the farce

and satire. Plautus’s play Menaechmi is a

great example and connects us to Shakespeare’s Comedy

of Errors. Wisely, the great English bard here almost slavishly

imitates the Plautus play which is arguably superior to

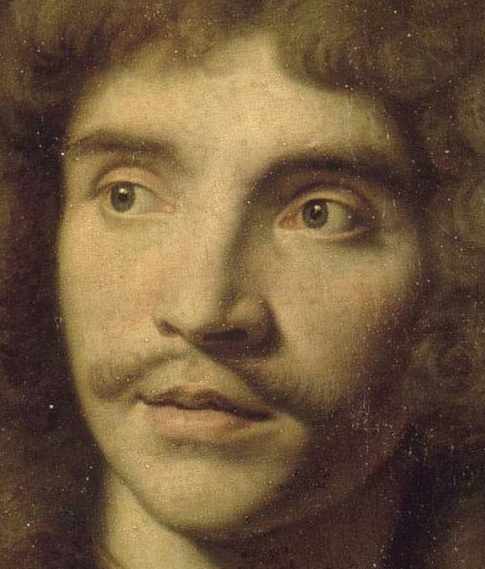

his own early effort. Moliere later adheres to the same

farce/satire structure, and much later Oscar Wilde

writers

Plautus and Terence are quick to adopt this successful formula

as they add versification, disguise, mistaken identity,

situational irony and other techniques to further the farce

and satire. Plautus’s play Menaechmi is a

great example and connects us to Shakespeare’s Comedy

of Errors. Wisely, the great English bard here almost slavishly

imitates the Plautus play which is arguably superior to

his own early effort. Moliere later adheres to the same

farce/satire structure, and much later Oscar Wilde follows suit.

follows suit.

Of course I

am hopelessly skipping so many great writers of comedy and

ignoring all of the other elements of their genius -- poetry,

characterization, melodrama, hyperbole etc. -- but it remains

essential that we recognize the farce/satire elements as

the unqualified necessities for success in so many instances

of comic history.

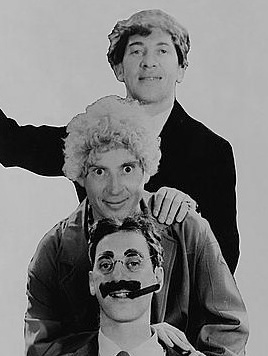

Because the

initial success in modern movies and television relied so

exclusively on farce ( Ben Turpin, Harold Lloyd, The Three

Stooges, Abbot and Costello, The Marx brothers) any discussion

of their comedy as art rarely occurred. Soupy Sales’s

pie-in-the-face shtick was the symbol of farcical  success.

No one wrote seriously about any inherent aesthetic merit

here.

success.

No one wrote seriously about any inherent aesthetic merit

here.

For the sake

of brevity I’m glossing over minstrelsy, burlesque

and vaudeville because they all were so heavily committed

to farce . . . So we move on to the joke tellers. There

are so many outstanding figures: Georgie Jessel, Burns and

Allen, Fred Allen, Henny Youngman, Jack Benny, Milton Berle,

Phil Silvers, and later Phyllis Diller, Joey Bishop, Estelle

Getty and Buddy Hackett . . . This list isn’t too

helpful because I’m leaving out so many great comic

talents and besides so many of the joke tellers incorporated

elements other than simple punch lines.

Finally, we

come to the standup “observation comics” that

I produced in shows beginning in the seventies. With these

performers, farce gives way almost always to satire. The

material is taken from current events, politics, social

commentary and human relationships -- all areas that are

immediately recognizable by audiences who have often had

the same experiences that the comic describes in his routine.

But these experiences become funny only if the performer

delivers the material skillfully utilizing crafts that are

usually taken for granted i.e. timing, voice, movement,

expression, pause and persona.

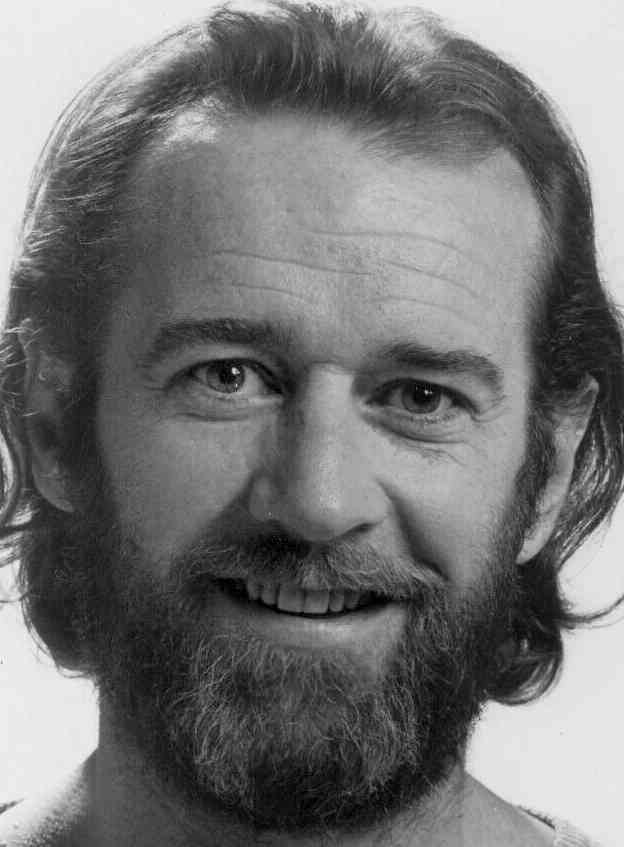

Among the many

comic talents that I encountered for years perhaps the one

that best represented what I just described was George Carlin.

His material was taken from the aforementioned areas and

his delivery included all of the craft elements I described.

Any narrative that I might offer illustrating his work will

ultimately fail to communicate his art. Luckily, readers

can quickly access YouTube which contains much of his best

work. A good example of what I’m discussing is a piece he described Advertising

and Bull. In this piece we can readily access

all of the craft elements described above. There are many

of his other pieces on YouTube which support my description

and once you log on you will find material from dozens of

observation comics. Among the most talented in 'material

selection' were figures such as Bill Maher, Jerry Seinfeld,

Rodney Dangerfield and Richard Lewis. These performers worked

in the shows I produced dozens of times. Among those comics

most talented in 'delivery' were Lenny Schultz, Gilbert

Gottfried, Sam Kinison and Andy Kaufman. The delivery that

these performers gave often involved farcical elements i.e.

humorous facial expressions, props, weird attire and fabricated

voices. Thus, farce didn’t disappear entirely with

some 'obervationists.'

I’m discussing is a piece he described Advertising

and Bull. In this piece we can readily access

all of the craft elements described above. There are many

of his other pieces on YouTube which support my description

and once you log on you will find material from dozens of

observation comics. Among the most talented in 'material

selection' were figures such as Bill Maher, Jerry Seinfeld,

Rodney Dangerfield and Richard Lewis. These performers worked

in the shows I produced dozens of times. Among those comics

most talented in 'delivery' were Lenny Schultz, Gilbert

Gottfried, Sam Kinison and Andy Kaufman. The delivery that

these performers gave often involved farcical elements i.e.

humorous facial expressions, props, weird attire and fabricated

voices. Thus, farce didn’t disappear entirely with

some 'obervationists.'

When helpful

critics analyze the 'artistic' elements of great playwrights,

composers, painters, sculptors, musicians etc. they usually

parse the talents the same way I have, judging the talent

in terms of material and delivery. But artistic reputations

usually take decades and even centuries to establish. Shakespeare

was just another Elizabethan playwright until decades later

when critics such as John Dryden and Samuel Johnson established

his greatness. John Keats was a minor romantic lyricist

until Alfred Tennyson uncovered his genius half a century

after his death. Impressionistic painters i.e. Renoir, Monet,

Degas, we’re banned from the French Royal Academy

and Salon for half a century. Igor Stravinsky was ostracized

after his initial performance of the Firebird Suite

. . . and on and on. Artistic recognition is difficult to

come by.

The problem

with some newer creators is even more insidious. Talented

Jazz musicians and standup comics are doomed at present

because their area of concentration or discipline is not

considered 'artistic' much less their individual contributions.

Discussions

and feuds over what kinds of creations can be considered

as art have been going on for centuries. I can only say

that in my experiences with standup comics I have found

it pretty easy to analyze their talent in the same way that

I have analyzed Shakespearean drama, classical music, masterpiece

painting, and other established arts for my university students.

Many critics who proselytize endlessly about what they consider

major arts or minor creations are parvenus; their analyses

are too often self-serving and result in injustices to creators.

Samuel Taylor

Coleridge operating in the same spirit as Aristotle iterated

principles that are the best for evaluating the contributions

of a creator and I will paraphrase them. Simply: What is

the artist trying to do?, How well has he done it?, and

What is the significance of what he has done?