HOW TO PRACTICE GOOD CONSENT

by

SUZANNAH WEISS

______________________________________________________

Suzannah Weiss is a freelance writer and editor

who currently serves as a contributing editor for

Teen Vogue

and

Complex. She authored a chapter of

Here We Are:

Feminism for the Real World. Her writing has also appeared

in

The Los Angeles Times, The Village Voice, Cosmopolitan,

Elle, Marie Claire, Harper’s Bazaar, Seventeen, Bitch, Bust,

Women’s Health, Paper, Paste, Redbook, Good Housekeeping,

Mic, Business Insider, Buzzfeed, The Huffington Post, Alternet,

Thought Catalog, Pop Sugar, xoJane, MEL, and much more. For

more of Suzannah's writing and thinking, please visit her

website.

Twitter link = @suzannahweiss

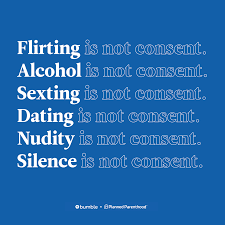

Thanks

to the #MeToo movement, people are becoming more conscious of

how they treat others' sexual boundaries. Yet there's still some

confusion over what constitutes sexual consent. Even those with

the best of intentions can disrespect others' boundaries if they

don't understand how to respect them.

That's

where Sexual Consent, a book forthcoming from MIT Press

in May 2019 by blogger, activist and University of the West of

England researcher Milena Popova, comes in. Sexual Consent

teaches readers the concepts and terminology that are essential

to know if you want  to

practice good consent in your sex life.

to

practice good consent in your sex life.

"We

tend to think of consent as this very binary thing," Popova

tells Bustle. "It was either consent or it was rape,

and there's a very sharp dividing line between them. That's the

way the law thinks about it: If we can't prove it was rape, then

it must have been consent, the end. But actually, like pretty

much anything to do with sex, consent can be quite messy. It involves

humans and emotions. And it's enmeshed in all sorts of social

and power structures."

What

makes consent even more complex is that even when people do seemingly

consent, they're often consenting under pressure, either from

a partner or from society, which isn't true consent. Consent is

"shaped as much -- if not more -- by what we think we should

do and want as by what we actually want," says Popova. "So,

that legalistic perspective -- it was either one or the other

-- isn't very helpful on a day-to-day level if we want to make

sure the sex we're engaging in is genuinely consensual. On that

level, we need to bear in mind that we and our partners are complicated,

messy human beings, be attuned to each other's feelings and responses,

and respect each other's boundaries." Here are some terms

and concepts from Sexual Consent that you should learn

if you want to be the most respectful partner you can be.

SEXUAL

SCRIPTS

A sexual

script is a societal idea of how sex is supposed to go. For instance,

the dominant sexual script in American society goes something

like "kissing, foreplay, intercourse." The problem with

this is that it promotes a limited definition of sex, which in

turn promotes a limited definition of sexual assault.

"Your

bodily autonomy is still violated by being kissed or touched against

your will, not only by being penetrated against your will,"

Popova writes. Therefore, we need to stop viewing activities like

kissing and touching as expressions of consent for intercourse

(which they're not) and view them as acts that require consent

in of themselves. And we shouldn’t make assumptions about

what someone  consents

to based on sexual scripts; we should take the time to find out

what kinds of sex they enjoy.

consents

to based on sexual scripts; we should take the time to find out

what kinds of sex they enjoy.

CONDITIONAL

CONSENT

Consenting

to a sexual act does not mean consenting to every form of it at

any time. For example, if someone consents to intercourse, they

may only be consenting on the condition that a condom is used

-- which is why stealthing (non-consensual condom removal) is

a form of sexual assault.

"Saying

that consent can be conditional means that you can say 'yes, I

want to do this with you, but only on these conditions,'"

Popova writes. "Consent to penetration can be conditional

on condom use, consent to oral sex can be conditional on the use

of dental dams, and consent to having an open relationship or

multiple partners can be conditional on regular STI testing. But

there are also other situations where conditional consent applies.

For sex workers, for instance, consent is conditional on being

paid for their work." So, again, it's important not to make

assumptions and to discuss the specifics of what your partner

wants.

CONTRACTUAL

CONSENT

Unfortunately,

our society often views consent as contractual -- i.e., like an

economic exchange. Contractual consent is "the idea that

certain unrelated actions by one partner generate an obligation

for another partner to engage in sexual activity," Popova

writes. The stereotypical situation, for example, is that a woman

provides sex in exchange for long-term commitment or financial

support from a man.

The problem

with this model is that it implies that one person owes the other

person sex, rather than both people having it because they mutually

want to. Even in cases like sex work where someone has sex to

get something from their partner, this person always has the right

to withdraw consent.

CONTINUOUS

CONSENT

Speaking

of withdrawing consent, anybody can always withdraw consent at

any time. Consent must be continuous, which means that "you

are allowed to change your mind about what you are doing at any

point during a sexual situation, for any reason," Popova

writes. This also means it's important to keep checking in with

your partner to make sure they consent to each act you engage

in.

If

you're not comfortable with a sexual encounter, you can just say,

"Hey, I don’t want to do this anymore," Popova

suggests. You can also say something more specific to take the

encounter in a new direction, like, “Let’s do something

else that’s fun for both of us.”

If

you're not comfortable with a sexual encounter, you can just say,

"Hey, I don’t want to do this anymore," Popova

suggests. You can also say something more specific to take the

encounter in a new direction, like, “Let’s do something

else that’s fun for both of us.”

INDIRECT

COMMUNICATION

People

sometimes say that sexual assault victims should have been firmer

in saying "no" to make it clear that the advances weren't

welcome. But women are socialized to avoid direct communication

like this, Popova points out, and often, subtler forms of communication

are clear enough for the perpetrator to get the message -- they

just decide to take advantage of the indirect communication by

pretending it's unclear.

After

all, there are other situations where people accept indirect forms

of "no." For example, to decline an invitation, you

might say, “I can’t go out for a beer tonight, I’m

playing football" or “Not right now, thanks, but maybe

later," Popova points out. It's not always easy to just say

"no." That's why affirmative consent, where only "yes"

means yes, is a better standard than "no means no."

NON-SEXUAL

CONSENT

The call

to honour people's bodily autonomy applies to much more than sex.

Teaching people about consent also means teaching children they

don't have to hug their relatives, teaching adolescents not to

pressure anyone to go out with them, and teaching people to ask

before making physical contact with anyone.

Whatever

your boundaries are, people should respect all of them just as

they'd respect your sexual boundaries. "Preferring to be

addressed by a nickname rather than your full name may be a boundary,"

Povova writes. "Being comfortable in small groups but not

in large gatherings may be a boundary. Not liking certain foods

or preferring handshakes over hugs are also examples of nonsexual

boundaries we may set for ourselves."

INTIMATE

PARTNER VIOLENCE

The stereotype

of a sexual assault occurring at the hands of a stranger in a

dark alley does not represent most assaults. In fact, one in 10

people has been the victim of rape by a partner, according to

the Washington Coalition of Sexual Assault Programs. Due to traditional

views of marriage as the possession of a woman by a man, many

people don't even realize that non-consensual sexual activity

with a spouse or intimate partner is assault. Spousal rape is

even treated differently than other kinds of rape in some U.S.

states.

No matter

how long you've been dating someone, it's important to make sure

they consent to anything sexual you do together. "While in

saying 'I do' you promise to do quite a lot of things, letting

your spouse use your body for their sexual gratification whenever

they want to is not one of them," writes Popova.

The #MeToo

movement has helped more sexual assault survivors come forward

and feel validated that what happened to them was wrong and not

their fault. But we need to go further than that by practicing

good consent in our own sex lives, and learning the nuances of

affirmative consent is a good place to start. Talk to your partner

about boundaries before you're even in the bedroom, check in with

them while you're having sex, and talk about your sex life afterward

to make sure everybody's feeling comfortable and respected.