broken promises in the promised land

I'M BLACK AND JEWISH AND ISRAEL ISN'T MY

HOME

by

TAMAR MANASSEH

_______________________________________________________________________

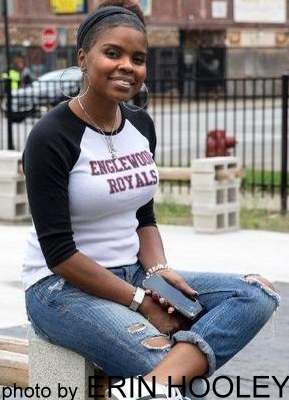

Tamar

Manasseh is the founder and president of Mothers Against Senseless

Killings. Follow her on Twitter @TamarManasseh

I recently

received an invitation from the Consulate General of Israel in

Chicago to visit Israel. I should have felt proud. I should have

felt honoured. I should have felt something. But I didn’t.

Imagine, a trip to the Holy Land, the land promised by God to

Abraham: I’d wanted to go for so long, but now that the

opportunity was being handed to me, I didn’t know how I

could do it.

From

the time I was a student at Jewish day school, I’ve been

preparing myself for my inevitable pilgrimage to the land of our

ancestors. Many in the community I grew up in had strong connections

to Israel. Some had family there, others were educated there.

A few went to Israel to join the army. They looked as if they

were at home in the homeland of the Jewish people. At home like

I wanted to be, and imagined myself one day being.

From

the time I was a student at Jewish day school, I’ve been

preparing myself for my inevitable pilgrimage to the land of our

ancestors. Many in the community I grew up in had strong connections

to Israel. Some had family there, others were educated there.

A few went to Israel to join the army. They looked as if they

were at home in the homeland of the Jewish people. At home like

I wanted to be, and imagined myself one day being.

My trip

would be beautiful, I thought growing up. I would climb Masada

at dawn, float on the Dead Sea and, of course, I would pray at

the Kotel, the holiest site in the Jewish world. I imagined that

I’d be overcome by the sheer magnitude of the moment. I

could almost hear the earth-shattering echoes of the voices of

millennia of our revered ancestors and teachers. Just imagining

the trip, I could already feel the joy of becoming a part of the

history of that place, standing steps away from the wall I had

spent a lifetime turning toward, eastward in prayer.

But

I started to notice that the stories of people flourishing in

Israel all had something in common: They were about white Jews.

At some point, I realized that I didn’t have a single friend

who was Jewish and of African descent whose stories made me want

to book a flight.

I’m

from Chicago, so I grew up hearing the stories of the Hebrew Israelites,

Chicagoans who had relinquished their American citizenship to

return to the land of the patriarchs, only to be denied Israeli

citizenship and left stateless. Israel rejected the Black Hebrews

as authentic Jews, insisting they convert to Judaism to be recognized

as full citizens. They refused. Only in 2009, four decades after

their arrival, did Israel grant some Israelites citizenship.

Every

Israelite I had ever met had a horror story to tell. Their stories

didn’t conjure up the idea of a land flowing with milk and

honey. More like poverty and discrimination.

Over

the years, I heard and read more and more stories and personal

accounts that terrified me. Ironically enough, at the same time

so many of these revelations were being made, the choir at my

predominately African-American synagogue was learning a new and

more soulful tune for “Hatikvah,” Israel’s national

anthem, even as I was coming to terms with the fact that my soul

did not feel welcome in the land for which we so beautifully express

our love.

The

more I learned and the more I read, the more difficult it became

to sing the song. I read about the treatment of Mizrahi Jews,

who are discriminated against regularly. I read about Ashkenazim

who don’t want their children to attend the same schools

as Jews of North African descent. Soon after that I read about

the Ethiopian Kessim being forced to give up their age-old traditions

and conform to more traditional Jewish standards, even though

their traditions predated the Orthodox practices of European Jewry.

I read about how Ethiopian Jews face police brutality and discrimination

from employers. Ethiopian supermodel Tahunia Rubel called Israel

“one of the most racist countries in the world.”

Most

recently, I read how Israel decided to close the Holot detention

center where it incarcerated refugees from Africa. These Sudanese

and Eritrean refugees now face a choice: be deported to Rwanda,

or go to jail. This week, I read about how the Ministry of Interior

announced that Israel will begin issuing notices to African migrants;

they have until April to leave.

This

certainly was not my Promised Land. The more I read about this

very young country that I fell in love with as a child, the less

it sounded like my homeland. It doesn’t say anywhere that

Jews like me aren’t welcome in Israel, but Israel has shown

me, repeatedly, that this is true. How can I trust that I won’t

be swept up in the transport of Eritrean and Sudanese being deported

to, of all places, Rwanda? If Ashkenazi women can be physically

attacked while praying at the Western Wall, what might happen

to a black woman doing the same? What if I’m like the young

man from Kenya a few months ago, and I’m never allowed to

even leave the airport?

I love

to sing: in the car, on a stage, in a choir, in the shower. However,

I will probably never sing “Hatikvah” again. And if

I were younger I might even take a knee. In the same vein, I’ll

probably remove “L’shanah Haba’ah b’Yerushalayim”

from my Passover Seder song list.

Let’s

face it: I probably won’t be there, next year or ever.