Nick

Catalano is a TV writer/producer and Professor of Literature

and Music at Pace University. He reviews books and music for

several journals and is the author of Clifford

Brown: The Life and Art of the Legendary Jazz Trumpeter,

New York

Nights: Performing, Producing and Writing in Gotham

and A

New Yorker at Sea. His latest book, Tales

of a Hamptons Sailor, is now available. For Nick's

reviews, visit his website: www.nickcatalano.net

Huge

population segments on both sides of the Atlantic have grown

up in a bubble -- under the impression that their long running

democracies will simply continue uninterrupted far into the

future. The recent Trump phenomenon with its rightist swings

against democratic traditions such as immigration, voting credentials,

health care and social equality have alarmed elders who see

similarities to such issues in the fascism of Nazi Germany early

in their lifetime. Yet others who have no historical recollections

feel no real dangers.

Despite

the outrage of Trump and his right wing preaching, a more ominous

trend against democracy exists close by in our own hemisphere

and in Europe. Elections in Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Brazil,

Paraguay, Venezuela and other countries for extreme right-wing

candidates have sprung up suddenly. The trend has acquired the

term ‘populism’ or as Trump has iterated ‘Nationalism,’

but that is a euphemism for autocracy as anyone with a knowledge

of history can see. Brazil’s Bolsonaro and Hungary’s

Orban articulate rhetoric right out of Mein Kampf while other

populist rulers express similar sentiments.

Nevertheless,

the wave of democratic societies that followed the crumbling

of monarchies and oligarchies since the time of Columbus has

been inspirational. The slogans and traditions adopted by the

American and French revolutions have shaped many of the values

and governments of the modern world and resulted in widespread

belief that the planet has achieved an important punctuation

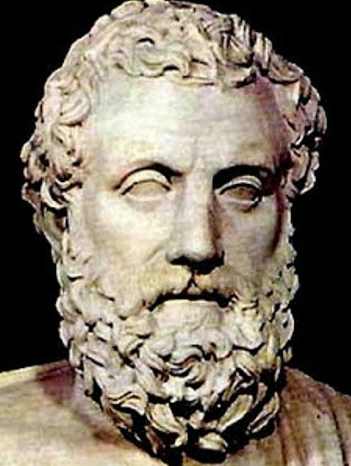

mark in human evolution. Many historians look back on the origins

of democracy in ancient Greece and proudly declare that its

legacy has successful counterparts in the modern world. Indeed

the goal of free elections and jury trials initiated by the

ancient Athenians has been the hallmark of countries everywhere.

The triumphant drumbeat of democracy still resonates loudly.

But

the parades and flag-waving of recent millennia have often failed

to note the moment to moment stumblings of democracy through

the ages. Its uneven development and evolution are nowhere as

triumphant as many think. Even the beacon of democracy in ancient

Greece has a history that bears a look back in the context of

the recent right-wing activity.

The

‘miracle’ of democracy in fifth-century Athens did

not spring up ex nihilo. A retrospection at least a

century and a half to the time of Homer is necessary to understand

the struggles toward societal freedom that the Greeks undertook.

Beginning

with Draco (620 B.C. -- some of whose ‘Draconian’

laws re homicide have become infamous) reforms were instituted

to try to establish fixed principles of justice that would override

the personal preferences of judges; the role of state government

had begun to evolve. Later, in the 6th century, Solon drew attention

to the problem of the wealthy class having advantage over the

poor in legislative decision-making (difficulty that persists

to the present day). He also instituted economic measures and

offered skilled craftsmen from abroad citizenship if they would

settle in Attica (the first move toward immigration). In addition,

he tweaked the justice system to allow male neighbors of victims

to bring forth indictments if they witnessed crimes. Accordingly,

once the sole concern of families, justice now became the business

of the community.

Unluckily,

because some of Solon’s laws allowed most citizens to

compete for political office, they probably played a role in

fostering civil strife. Also, the increased freedom under Solon

led to tribal groups whose competition for societal advantages

predictably caused further conflict. So a pattern developed:

the more autocracy, the less freedom; the more freedom the more

tribal squabbles.

THE

CONVOLUTIONS OF DEMOCRACY

As

the search for a more perfect government continued to convolute,

the ‘democratic’ momentum stalled, often reverting

back to autonomous rule. In came the time of Peisistratus and

his sons -- historians use the word ‘tyranny’ for

this regime -- but despite autocratic movement some of the earlier

marches to freedom managed to survive. This tyrant offered loans

to the needy so that the whole agricultural economy would benefit.

In fact, his autocratic policies ironically resulted in a furtherance

of democracy because when the last of his sons was expelled

in 510 B.C. all non-Peisistrads, rich and poor, found themselves

in surprisingly similar circumstances. That situation set the

stage for a return to the earlier egalitarianism but predictably,

also a return to factional strife.

Now

into power came Cleisthenes. He was strongly dedicated to reform

and a furtherance of freedom for all. In short order he revised

the older and sometimes ignored Athenian constitution that had

had a topsy-turvy history under the aforementioned regimes,

organized a boule (somewhat presaging the senates of

future governments) and focused on the enhancement of the Assembly

as the principal instrument of legislative power.

Now

into power came Cleisthenes. He was strongly dedicated to reform

and a furtherance of freedom for all. In short order he revised

the older and sometimes ignored Athenian constitution that had

had a topsy-turvy history under the aforementioned regimes,

organized a boule (somewhat presaging the senates of

future governments) and focused on the enhancement of the Assembly

as the principal instrument of legislative power.

So

by 505 B.C. the system of ‘pure’ democracy finally

arrived and all citizens rich and poor could attend Assembly

meetings on the Pnyx (a famous hill facing the Acropolis), speak

their minds and vote on the agenda.

To

the present day we celebrate this epic time of the 5th century

in classical Greece. Most significantly, this onset of previously

unavailable political and societal freedom spurned the golden

age of culture and science which followed. For 2500 years we

have re-visited this age and held it sacrosanct in the annals

of human evolution. The achievements of Plato, Socrates, Sophocles,

Aristotle and so many others are unmatched. And the arrival

of real democracy, after as we have seen, a millennium of governmental

experimentation, obviously played an enormous role in the cultural

activity.

Since

those heady years in ancient Greece no political system has

been held in higher esteem. And, in the modern era, following

the ignominious dictatorships we spoke of before, overwhelming

numbers of the world’s nations have rushed headlong to

adopt democratic systems.

However,

if we return for a moment to classical Athens and take a closer

look, the picture darkens quickly.

After

only a few decades in the fifth century of intoxicating universal

participatory democracy, fissures and cracks developed. Battles

with neighbouring city-states (particularly Sparta) which had

often occurred before, began to accelerate and the 25 year Peloponnesian

War began in 431 B.C. Plague broke out (over 50,000 Athenians

died) and everyone suffered; the smooth running trade economy

all over the Mediterranean eroded suddenly; wealthy citizens

began to mistrust the masses. These difficulties led to increasing

squabbles in the Assembly and new power struggles. The miraculous

threads of equality began to unwind.

After

Athens suffered a huge military defeat in Sicily, democracy

suffered its first of many convolutions in 413 B.C. when Athenians

placed decision-making in the hands of ten Oligarchs. In 411

the Assembly, symbol of the purest democracy the world was ever

to see, voted itself out of existence.

Reactionary

oligarchic experiments followed: first a council of 400, then

an evolution into a council of 5000. Finally, the war, the deteriorating

economy, and old factionalism virtually wrecked the democracy

and in 404 a government of 30 tyrants assumed power.

The

proud voice of Democracy became hoarse and then silenced by

the events described. Such events – war, economic hardship,

tribal factionalism – had struck down widespread democratic

freedom in Athens and would continue to stifle egalitarian government

efforts far into the future.

As

we said initially, those forces are certainly at work today

and it remains to be seen if western democracy can continue

to thrive or will suffer some catastrophic disintegration into

autocratic or even tyrannical rule.