part II

THUS SPAKE CAMILLE PAGLIA

interviewed by

TYLER COWEN

____________________________________________________

COWEN:

You can consume, absorb, experience a remarkable number, amount,

and diversity of culture products, music, art, architecture, interior

design, fashion, whatever, right?

PAGLIA:

Yes.

COWEN:

Just a very prosaic question, in terms of your own time management,

how is it that you do what you do? What is your method, so to

speak? What is your diet?

PAGLIA:

It’s a lifestyle of observation. I feel that the basis of

my work is not only the care I take with writing, with my quality

controls, my prose, but also my observation. It’s 24/7.

I’m always observing. I don’t sit in a university.

I never go to conferences. That is a terrible mistake. A conference

is like overlaying the same insular ideology on top of it. I am

always listening to conversations at the shopping mall.

COWEN:

Radio.

PAGLIA:

I adore radio. The radio is fantastic, any show on radio, the

talk shows, political talk shows, but also the sports shows. The

sports shows are the only place that you can hear on radio actual

working class voices calling in. “I want to talk about what

happened in the game on Monday,” and what they would do

if they had $2 million, and who they would hire.

It’s fantastic. My writer’s voice is actually very

-- rather than these novelists with their recherché lingo

and so on, my actual writing voice is very influenced by the way

English is spoken today by people and often men on radio. You

get this high impact sound, you see. On lamb vindaloo, LSD, and

other mental stimulants

COWEN:

You once wrote, I quote, “My substitute for LSD was Indian

food,” and by that, you meant lamb vindaloo.

PAGLIA:

Yes.

COWEN:

You stand by this.

PAGLIA:

Yes, I’ve been in a rut on lamb vindaloo. Every time I go

to an Indian restaurant, I say “Now, I’m going to

try something new.” But, no, I must go back to the lamb

vindaloo. All I know is it’s like an ecstasy for me, the

lamb vindaloo.

COWEN:

How would you describe your views on astrology? A reader wrote

to me, asked me to ask you.

PAGLIA:

Wait! Wait! You mentioned LSD, can I say something else about

that?

COWEN:

Sure, LSD, please.

PAGLIA:

Now, LSD, I never took it, thank God. I never took drugs. I didn’t

believe it. I thought “What is this untested thing?”

I thought, “A little wine, beer, all these things have like

thousands of years behind them.”

COWEN:

Lamb vindaloo.

PAGLIA:

Right. And so LSD, I’m so glad I never took it. Everyone

around me was taking LSD. People who did take LSD and survived

will still say things like, “Well, I’m really glad

I did because I.” Everyone who says that, I feel, actually

never attained the level of accomplishment that they should have

in terms of whatever their vision had been. I think LSD gave vision.

It gave vision, but then it deprived people of the ability to

translate that vision into material form for the present and for

posterity. But I still remain very oriented toward the LSD vision.

I feel I took LSD because I have the music. With “Bathing

at Baxter’s,” Jefferson Airplane, the first people

to be using [makes sound] like this. Distortions of The Byrds,

“Eight Miles High,” I adore that song.

PAGLIA:

Right. And so LSD, I’m so glad I never took it. Everyone

around me was taking LSD. People who did take LSD and survived

will still say things like, “Well, I’m really glad

I did because I.” Everyone who says that, I feel, actually

never attained the level of accomplishment that they should have

in terms of whatever their vision had been. I think LSD gave vision.

It gave vision, but then it deprived people of the ability to

translate that vision into material form for the present and for

posterity. But I still remain very oriented toward the LSD vision.

I feel I took LSD because I have the music. With “Bathing

at Baxter’s,” Jefferson Airplane, the first people

to be using [makes sound] like this. Distortions of The Byrds,

“Eight Miles High,” I adore that song.

I feel

I’m in that psychedelic world. I’ve sometimes said

that what I do is psychedelic criticism. Because it is metaphysical,

it is visionary. I have a vision. I have a vision that’s

bigger than society. That’s the problem with the Marxist

approach. I believe the Marxist approach is useful. Arnold Hauser’s

The Social History of Art is one of the most influential

things on me. It’s a Marxist perspective.

Indeed,

my work is always very attentive to the social context of anything.

But what Marxism lacks is that larger vision of the universe.

There are all kinds of questions and issues about human life that

Marxism has no answers for. It doesn’t see nature. What

kind of a vision doesn’t see nature, could only see society?

This is what’s happening. We have all these graduates of

the elite schools, whereas my generation was all into cosmic consciousness,

Hinduism, Buddhism.

I feel

that is the true multiculturalism. I’ve been arguing for

that for 25 years. I’ve been saying that if you want true

multiculturalism, you have to present world cultures, including

religion. Religion is extremely important. The most complex systems

human beings have ever devised were the great religions of the

world.

COWEN:

Past Arnold Hauser, past Norman Brown, who are the contemporary

writers and thinkers who influence you now who are writing serious

books on either the world cultures or anything else?

PAGLIA:

Is there anyone left writing serious books?

I’m

trying to think who has written a serious book I’m interested

in right now. Listen, there’s no one I would say, “Oh,

so-and-so’s book is coming.” What? They’re dead.

The people who I admire are long dead.

Unfortunately,

it’s a terrible destruction. My work looks very strange

and idiosyncratic because I’m alone. I’m alone and

all the people who should have been writing interesting, quirky

books, as I do, are dead or their brains were destroyed by LSD.

It’s

one or the other. I knew so many, to me, brilliant minds in graduate

school and early in my teaching career at Bennington College,

really brilliant minds. I had great hopes for them and for what

they would do. Then they couldn’t get anything done. For

whatever reason, they couldn’t. They didn’t have the

resilience to continue against obstacles.

When

their work would get rejected, they would become discouraged and

would stop. Rejection simply infuriates me. I’ll say, “Well,

I’ll have my revenge on you in the afterlife.” I’ll

be around, and you’ll be dead. I don’t know, it’s

an Italian thing. What can I say?

COWEN:

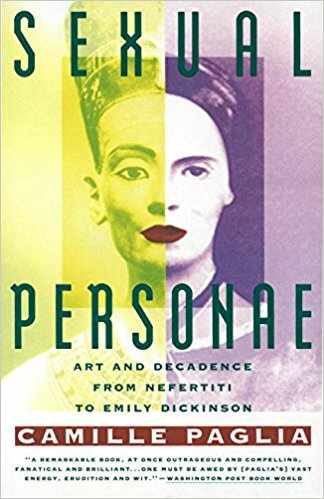

This is Sexual Personae, your best known book, which

I recommend to everyone, if you haven’t already read it.

PAGLIA:

It took 20 years.

COWEN:

Read all of it. My favourite chapter is the Edmund Spenser chapter,

by the way.

PAGLIA:

Really? Why? How strange.

COWEN:

That brought Spenser to life for me.

PAGLIA:

Oh, my goodness.

COWEN:

I realized it was a wonderful book.

PAGLIA:

Oh, my God.

COWEN:

I had no idea. I thought of it as old and fusty and stuffy.

PAGLIA:

Oh, yes.

COWEN:

And 100 percent because of you.

PAGLIA:

We should tell them that The Faerie Queene is quite forgotten

now, but it had enormous impact, Spenser’s Faerie Queene,

on Shakespeare, and on the Romantic poets, and so on, and so forth.

The Faerie Queene had been taught in this very moralistic way.

But in my chapter, I showed that it was entirely a work of pornography,

equal to the Marquis de Sade.

PAGLIA:

We should tell them that The Faerie Queene is quite forgotten

now, but it had enormous impact, Spenser’s Faerie Queene,

on Shakespeare, and on the Romantic poets, and so on, and so forth.

The Faerie Queene had been taught in this very moralistic way.

But in my chapter, I showed that it was entirely a work of pornography,

equal to the Marquis de Sade.

COWEN:

The cover image is Queen Nefertiti in the Neues Museum in Berlin.

Recently in the news, we’ve seen that someone has scanned

the bust.

PAGLIA:

Oh, that’s awesome.

COWEN:

And it will soon be possible using 3-D printers to print out your

own ‘copy’ of Nefertiti. How do you feel about this?

PAGLIA:

To me, archaeology is one of my master tropes. What can I say?

“The Bust of Nefertiti,” discovered in 1912, and it’s

amazing. We’ve known it for like a century. It’s extraordinary,

isn’t it, how it’s become such a symbol of art.

I should

say that the push of countries like Greece and Egypt to recover

their masterpieces from where they were taken and scattered around

the world, I think with what’s been happening with ISIS,

and the demolition of Palmyra and all kinds of things that have

happened, my attitude now is keep Nefertiti in Berlin, please.

Don’t send it back to Cairo.

COWEN:

Of all the aesthetic judgments in your writings, and you’ve

covered a lot of ground, but are there any where you really fundamentally

regret an earlier judgment and have revised it? Not in a marginal

way, which happens all the time, but really just thought, “Well,

I was wrong about that?”

PAGLIA:

Interesting. My early work, I’d worked on for so long that

it was like I had plenty of time for second thoughts and third

thoughts, and hundredth thoughts, so no. I can’t think of

anything offhand. Can I get back to you about that?

COWEN:

Sure. If you could travel to one place you haven’t been,

where would it be and why?

PAGLIA:

I’m like Huysmans’s aesthete, des Esseintes. I am

not a great fan of traveling. I just feel like it’s become

too onerous. No, I’m a mind traveler.

COWEN:

What is your unrealized dream in life?

PAGLIA:

My unrealized dream, to meet Catherine Deneuve. But I met her

once. I ran into her, smack ran into her once on 5th Avenue in

front of Saks. I know this is kind of bizarre.

COWEN:

It’s a realized dream?

PAGLIA:

Yes, but it was odd. I pursued her into the glove department and

forced her to sign my ticket envelope for the Fillmore East, where

I was seeing Jefferson Airplane. To have a conversation with Catherine

Deneuve, shall we say. A civilized conversation.

COWEN:

On that topic, one of your books, The Birds, about the Alfred

Hitchcock movie – a great book, one of my favourite movies.

Going back to that time, if you had the opportunity to date either

Suzanne Pleshette or Tippi Hedren -- .

PAGLIA:

I don’t date. I’m just a mad nun.

COWEN:

Hypothetically.

PAGLIA:

Dating is so banal.

COWEN:

Tea with Suzanne Pleshette or Tippi Hedren.

PAGLIA:

Tippi Hedren invited me to lunch on Rodeo Drive after that. I

was, I don’t know, giving some speech on Shakespeare at

the Los Angeles Public Library. She invited to thank me for writing

this and I met her. She had a stack of 12 of these books, and

I signed them for her. She was the most elegant and wonderful,

warm woman.

I didn’t

have much time. She invited me to go to the ranch and see all

the animals and the lions that she collected and so on.

Suzanne

Pleshette, I think, was absolutely underutilized by Hollywood.

What an intelligent, knife-sharp character, she was. In fact,

I recently, in one of my Salon columns, compared her to Lena Dunham.

Lena Dunham is the product of exactly the same world. If you want

to see the difference between Suzanne Pleshette, the sophisticated

Suzanne Pleshette, and Lena Dunham. You want to see the decline

that we’re in the middle of right now, there it is.

I wrote this. The British Film Institute asked me to write on

a film and I said, “How about The Birds?” and I did.

I wrote this book, and it was universally panned by the film journals,

which said about it, “This book does nothing. This book

does nothing.” By which they meant that it wasn’t

poststructuralist, it wasn’t postmodernist.

There

wasn’t a lot of theory. I wasn’t citing, you know,

the male gaze, and et cetera, et cetera. All this book does is

go through the film The Birds from beginning to end, scene by

scene by scene, and pays attention to the film itself.

Slowly

it’s made its way. Now here it is. It was 1998 when that

came out, and it’s starting to happen now. Routledge is

a publisher that’s done nothing but this theory stuff. They’re

starting to go, “Hmm. Maybe there was something in her --

I’m hoping.”

I’m

just trying to inspire graduate students to rebel against this

horrible fascism that forces theory onto them before they expose

themselves to everything that’s wonderful and imaginative

in the history of literature and art. I believe that paying minute

attention to the actual work itself is the mission of criticism.

I am hopelessly old-fashioned. Because that’s not what you’re

supposed to do. You’re supposed to mention Foucault 59 times

in one paragraph. What a windbag that guy is, I’m telling

you. Foucault is nothing. He’s nothing. He pretends to be

such a mastermind, but in fact he’s just a collection of

influences and one of the biggest influences on him was Erving

Goffman, of Philadelphia, who was the great sociologist -- originally

Canadian -- who wrote The Presentation of Self in Everyday

Life. All the things that were an influence on me influenced

Foucault.

You have

all these people thinking Foucault was some sort of innovative

figure in the history of modern sociology or intellect, and he

wasn’t. It is a disease in these people. Everywhere, every

single university in the United States, every single gender studies

department, they’re impregnated with Foucault. That’s

why we have graduates who know nothing.

COWEN:

Do you like Marnie, the Hitchcock movie?

PAGLIA:

Do I like Marnie? Certainly, there are parts I like.

COWEN:

But it goes askew in a way The Birds doesn’t.

PAGLIA:

Yes. There are problems with it. So much was toxic going on on

the set between Hitchcock and Tippi Hedren at that point, and

so on. But there are wonderful things in Marnie. On the simple

life

COWEN:

If you were to take someone who had read all or almost all of

your work, and they had a sense of you and read a lot of your

columns, watched some of your talks online, whatever, and they

get a picture of you, but you wanted to tell them one thing about

you that maybe they wouldn’t get from any of that about

what motivates you, what drives you, what your life is actually

like, what is -- ?

PAGLIA:

My life is completely mundane. I’m a schoolmarm. That’s

all I am. I had the wisdom, having been raised Catholic, that

once I finally became known, at age 43, I didn’t change

one thing about my life. Not one thing. I didn’t move to

New York. I didn’t go chasing around. I didn’t get

a speakers’ bureau. All that stuff. I have a cousin who’s

a nun, and I have all these bishops and priests and sextons and

so on in the family.

I just

try to keep to reality. Because I know that the basis of my work

is the closeness with which I live to ordinary life. I hate the

elites. I hate parties. I don’t have any book parties or

anything like that.

PAGLIA:

I think that people, they want success and they want material

advantages and so on. Being a writer is just scut work. Being

a teacher, that’s what Susan Sontag also did wrong. Susan

Sontag began in graduate school. “Oh, it’s so boring.”

She did a little teaching and then went off and became a luminary.

She was a big luminary, a big giant dirigible luminary her whole

life.

Nothing that she said made any sense actually over time, eventually.

She loved to hold court at parties. It’s notorious. People

who remember her, “She was so brilliant. I saw her at this

dinner party. Everyone was in awe.”

People

who go to dinner parties to impress other people, it is such BS.

Susan Sontag over time, her work got less and less meaningful,

even though people worship at the shrine of Sontag. You try to

quote her on anything. What can you quote her on? There’s

nothing important.

COWEN:

Camp? Photography?

PAGLIA:

Quote a sentence from Susan Sontag, a great sentence. You can’t.

The only sentence was the one she regretted, “The white

race is the cancer of history.” That’s the one she

retracted finally when she got cancer. Remember? She realized

how horrible that was. That’s the only thing that you can

quote her on. She’s not quotable, because there’s

all this sleight of hand that she’s doing. She’s taking

material that she borrows from others, or places that she’s

been personally at a time when downtown New York was very exciting,

so basically it was a kind of transcription of her everyday life.

I think

the best thing she did probably was for me, she wrote a very witty

thing, “The Imagination of Disaster.” I like that

essay a lot, which is all about the horror films of the 1950s.

I thought if she only had stayed like that, unpretentious and

really engaging with actual materials. But Susan Sontag, basically

her life became going from lecture to lecture, being hailed as

the Great One, and being so detached from ordinary life. Whereas,

when you’re a teacher, like a classroom teacher, as I’ve

been for 40 years, the kids have no idea that I write books. Now

and then, someone’s father will say, “She writes books,”

and they’ll come and say, “My father is a fan of yours.”

“Oh, really? That’s so nice,” I’ll say.

Anyway,

the point is all these professors at Harvard and Princeton and

Yale, they have the graduate students are paying court to them,

because they need letters of recommendations. Hello, they want

something from you. They’re so used to “They’re

so grand” and so on.

I go

in, and it’s like, “We need more chairs.” “What’s

wrong?” “The curtain is wrong.” I’m always

in touch with the janitors, infrastructure, condition of the buildings.

I deal with everyday life. I’m not treated like a queen.

I’m just like an ordinary schoolmarm working like a horse,

pulling the plow. I think that’s a really good idea for

writers is to have a job where you’re dealing with constant

frustrations, and problems, and so on. I think that’s really

good for you.

COWEN:

Like Herman Melville, right?

PAGLIA:

Yes, yes.

COWEN:

Hunting whales is not easy.

PAGLIA:

Or Wallace Stevens. He kept going to the office, the insurance

company, every day.

COWEN:

My last question before they get to ask you, but I know there

are many people in this audience, or at least some, who are considering

some kind of life or career in the world of ideas. If you were

to offer them a piece of advice based on your years struggling

with the infrastructure, and the number of chairs, and whatever

else, what would that be?

PAGLIA:

Get a job. Have a job. Again, that’s the real job. Every

time you have frustrations with the real job, you say, “This

is good.” This is good, because this is reality. This is

reality as everybody lives it. This thing of withdrawing from

the world to be a writer, I think, is a terrible mistake.

Number

one thing is constantly observing. My whole life, I’m constantly

jotting things down. Constantly. Just jot, jot, jot, jot. I’ll

have an idea. I’m cooking, and I have an idea, “Whoa,

whoa.” I have a lot of pieces of paper with tomato sauce

on them or whatever. I transfer these to cards or I transfer them

to notes.

I’m

just constantly open. Everything’s on all the time. I never

say, “This is important. This is not important.” That’s

why I got into popular culture at a time when popular culture

was out.

In fact,

there’s absolutely no doubt that at Yale Graduate School,

I lost huge credibility with the professors because of my endorsement

of not only film but Hollywood. When Hollywood was considered

crass entertainment and so on. Now, the media studies came in

very strongly after that, although highly theoretical. Not the

way I teach media studies.

I also

believe in following your own instincts and intuition, like there’s

something meaningful here. You don’t know what it is, but

you just keep it on the back burner. That’s basically how

I work is this, the constant observation. Also, I try to tell

my students, they never get the message really, but what I try

to say to them is nothing is boring. Nothing is boring. If you’re

bored, you’re boring.

Wherever you are, it’s exhausting. It’s frustrating.

I don’t know what. The plane has been cancelled and whatever.

After you get over your fury, you realize what opportunity is

there here to absorb something more from this experience, from

observing other people or whatever it is.

I think

there’s really no experience that you can have that there’s

not something in there that eventually you can’t use as

a part of your developing system.

Another

thing I have to say, anyone interested in ideas, do not read any

of the current books like Pierre Bourdieu and all that stuff.

Oh my God, it’s so incomplete. It’s really boring.

I believe in the library. The library is my shrine. It was my

shrine when I was researching Amelia Earhart. When I got to Yale,

Sterling Library was my shrine. I ransacked that building, oh

my God.

That’s

the thing, is that I’ve learned more from the old commentators.

James George Frazer, The Golden Bough, which was considered

completely gone but had a huge impact on “The Waste Land”

and other works of modernism. I’ve learned a great deal

from the commentators of the past, the historians of the past.

Now,

when I did Glittering Images, the actual nullity of current scholarship

became very exposed to me. Of course, I already knew about it,

but I really got objective proof of it. There’s 29 chapters

in it. Each artwork that I chose, I did a full research of what

had been said about that particular artwork, so I began chronologically.

I would

work, if it was an older work from the late 19th century, moving

through the decades to the present. There, oh my God, could you

see it, could you see the fall in the quality of scholarship in

our time from the 1980s on. I would move from these incredibly

erudite and wonderful sentences, beautiful stylus about art, late

19th century moving into the 20th century.

Still

solid into about the ’60s. And then the ’70s is kind

of holding there. All of a sudden comes the ’80s, ’90s,

2000s. All these people are pygmies. Pygmies, the people at the

elite schools. Let me say, the big art survey courses are being

dismantled. Hello? It used to be you had a two-semester course.

It would begin with cave art and move, in two semesters, down

to modernism.

Magnificent

structure, now abandoned wholesale except when students have protested,

like at Smith. My sister is a graduate of Smith, and was part

of the protest that got the survey restored.

Graduate

students in art history and art historians no longer have the

ability to teach the big picture, because all narratives are regarded

as fictional now, imperialistic fictions. The entire story of

art is not possible, and therefore, people know nothing.

AUDIENCE

MEMBER: Hi, thanks for coming. You mentioned your incident with

Catherine Deneuve, and you also talked about that in 1995 and

Playboy following her, and also having 599 pictures of Elizabeth

Taylor. You also mentioned how David Bowie had reached out to

you and wanted to meet you, you talked about how you weren’t

sure you would have wanted to, because you have to keep a respectful

distance from an artist of that towering stature.

You also

mentioned in that interview that obsession and genius are pretty

much the same thing, so where would you draw the line between

– let’s say you have an opportunity to meet someone

who’s very important to you, or contrive a meeting, or just

seek them out. Where do you draw the line between the obsession,

and I mean the Paglia kind of obsession, not the John Hinckley

kind?

PAGLIA:

I personally have never had this great desire, necessarily, to

meet the figures that I most admire in the arts, because I understand

that what they represent onscreen is something that is an artificial

construction. It’s not the reality.

I’ve

been working in art schools also my entire career, so I know.

I have dancers in my class. I have actors in my class, and I completely

understand the difference between the fallible real self, the

mundane real self, and the artistic self suddenly emerges within

what I call the temenos, which is the sacred precinct that I regard

as art.

Therefore,

when I encountered Catherine Deneuve by accident that day, and

I was at the peak of my obsession with her, it really almost ruined

my interest in her, because it’s like, “Oh, my God.”

It’s not the real Catherine Deneuve that I was so intent

on. It was this magical creation that is a result of her talent,

but also of the director’s own magical skills, and so on.

Oh, yes,

Elizabeth Taylor, I have 599 pictures, yes. People often say what’s

odd about that is not the number, but that I had counted them.

She represented to me everything -- the pure sexuality that had

been repressed during the Doris Day 1950s and early ’60s.

Butterfield 8 still remains for me a great pagan exhibition. Here

is Elizabeth Taylor as a high class call girl. Oh, my God, and

I had Jeanne Moreau and Monica Vitti and Anouk Aimée and

Melina Mercouri.

There

were so many phenomenal images that I was inundated with when

I was in high school and college, and what do these kids have

today? Taylor Swift? Oh, my God. She is such a fake. She poses

in things that she imagines are sexy and sultry, and it’s

so fake. Awful. At least Rihanna, who’s on dope most of

the time, and that’s why she looks so sultry. Rihanna’s

Instagrams are, to me, like a work of art. That’s the only

thing I’m following right now, I have to say, that’s

of equal importance, is Rihanna floating from one nightclub to

another, and yet some other fashionable thing, but back to your

question.

Oh,

David Bowie. I wrote this essay called “Theater of Gender:

David Bowie at the Climax of the Sexual Revolution.” I wrote

it for the Victoria and Albert exhibition catalog for the costume

show that they did that is now touring the world, and I consider

it one of my most important pieces, but it’s in the catalog.

I want

to get into my next essay collection, but with Bowie, see, Bowie

is different than Deneuve. Bowie is truly like a creative artist,

whereas Deneuve and Taylor are performers in other people’s

fictions. But Bowie was truly a master creator of a level that

just is staggering.

When

I did the research for that essay, I knocked out all over again

at the enormity of what he achieved, and also at how little has

been acknowledged, his deep knowledge of the visual arts, and

how he had been influenced by that. I found all kinds of little

details that showed his deep knowledge, his erudition about that.

It appears

to be that he did tell the V&A to invite me. That time, people

don’t know. What you’re talking about is where --

it was earlier in the 1990s, and a message came to my publisher

saying -- and it was conveyed to me by the publicist and my publisher

-- saying, “David Bowie wants your phone number,”

and I burst out laughing. I said, “That’s ridiculous.

Oh, boy. It’s just some fan trying to get it.” They

said, “David Bowie they claimed really wants your phone

number.” I said, “Is that the way David Bowie gets

in touch with you when he wants your phone number?” I laughed,

and I didn’t believe it. It was all so shadowy.

Only

now, only after I did the research for this Victoria and Albert

thing, did I realize that the reason it was so strange was that

he had fired his entire staff. He had fired his management. He

had fired his company, and dealing with the record companies and

so on after Berlin, and he only dealt with the world via friends.

That’s what was so strange about it. It was strange. I made

a mistake.

What

he wanted was he wanted to use an excerpt from Sexual Personae

on a record album in one of his lyrics. I’m like, “Oh,

my God.” It’s very embarrassing that that happened,

but that’s OK. I think there should be a distance, or a

sense of respect and reserve, with great artists.

AUDIENCE

MEMBER: My question is do you ever have any concern that modern

literature and eventually all the classics will have to be rewritten

so that in order to be understood, every fifth word will have

to be the word “like”?

PAGLIA:

Unfortunately, the sense of language in general, or just a respect

for language or interest in language is degenerating. I’m

someone who used to write down, always, I’d write down any

word I don’t know in what I’m reading. I would make

lists, and I would study the dictionary and etymologies, and now,

young people have no concern for language, per se.

The way

they communicate with each other and the email format now in text

is very truncated, and it’s why the writing on the web has

also degenerated horribly.

It used to be with newspapers and magazines, there was a space

limit, and that imposed a real kind of format. It forced you to

condense, and it gave a crispness to language. We’re in

a period now, I’m afraid that the ear for language is degenerating.

AUDIENCE

MEMBER: In my view, feminists have made a lot of progress in the

Western world in the last century, and I’m curious to know

if you think we’re close to basically achieving the goals

that were set out, or if the feminists will ever feel like the

fact that more women go to college these days, for example, is

a symbol of progress, or that they’ll never feel like the

job has been done?

PAGLIA:

Oh, no. I’m an equal opportunity feminist, by which I believe

that all obstacles to women’s advancement in the political

and professional realms should be removed.

What

I’m also saying is that there are huge areas of human life

that are not political that have to do with our private spiritual

nature, and that is a place where legislation will always be helpless

and hopeless and indeed, intrusive, so I think that feminism has

made enormous gains in terms of -- there was a time that women

were totally dependent on father, on husband, on brother, for

their survival.

Now,

women can be self-supporting, can live totally on their own. It’s

part of this whole Western world powered by capitalism that our

university curricula are now habitually always demeaning. Capitalism

made women’s emancipation possible.

I think

that the problem right now is that young women have been taught

that to somehow identify their own sense of personal unhappiness

with men, and men are responsible for our unhappiness, when in

fact, part of the issue is that we have lived as a species for

tens of thousands of year, where mating occurred early, where

you left your parents’ house, and had your own household,

and your own children.

Juliet,

in Romeo and Juliet, is 13 going on 14, and already,

she’s ready for marriage. In this life, we have a very long,

an unnaturally long period here, before women can attain some

sense of who they are as women.

It’s

not men. It’s not the patriarchy, and it’s ultimately

not a feminist issue. It has something to do with this very mechanical

system of the modern technological, professional world that has

emerged to replace the agrarian period, when there were multiple

generations living with each other, and women had a natural sense

of solidarity, being all together.

There

was the world of women, and the world of men, once. They didn’t

have that much to do with each other once. All the problems have

happened since we started having to deal with each other.

Part

I