part I

THUS SPAKE CAMILLE PAGLIA

interviewed by

TYLER COWEN

____________________________________________________

COWEN:

How do you feel about the fact that Silicon Valley dominates our

economy and culture? Is there any tech guru you’re interested

in?

PAGLIA:

Well, no. My last big tech guru was probably Marshall McLuhan.

Had a prophetic insight into what was about to happen. He’s

kind of the patron saint of my working on the web from the very

first issue of Salon in 1995. It’s hard to believe that

the web wasn’t taken seriously by already-established journalists.

There

was a major political reporter at the Boston Globe, for

example, who tried to pressure me not to write for the web. He

said, “Oh, no one takes the web seriously.” It’s

an enormous thing that’s happened. Which, of course, has

also sucked in a whole generation of young people, alas. That’s

all they know. I think we’re kind of on the downside of

that right now.

COWEN:

Glittering Images, and your other work, emphasized the

role of the iconic in Western and Eastern culture, the role of

the spectacular. Now here we have people, they look, they listen

on very small smartphones. Is this culture dead? But if the culture

was so splendid, why did people give it up so quickly?

PAGLIA:

The reason I wrote Glittering Images is because I felt

that there’s an avalanche of fragmented visual impressions

-- disconnected, glaring, tacky, badly designed -- that young

people are growing up in. I think it really is true that children’s

brains are being reshaped. The standard forms for logic and for

sequential information and for reasoning, everything’s kind

of disappearing. I tried to write a book where people would just

stare at an image for a certain length of time.

PAGLIA:

The reason I wrote Glittering Images is because I felt

that there’s an avalanche of fragmented visual impressions

-- disconnected, glaring, tacky, badly designed -- that young

people are growing up in. I think it really is true that children’s

brains are being reshaped. The standard forms for logic and for

sequential information and for reasoning, everything’s kind

of disappearing. I tried to write a book where people would just

stare at an image for a certain length of time.

I think

it’s getting worse and worse. Web design, which my school,

University of the Arts, teaches -- I think web design is in the

pits. I thought web design was moving into becoming a major genre

of the arts. I think we’re in a kind of swirling vortex

-- and yes, what you mentioned about the miniaturization of image

is terrible.

I was

raised in a time, 1950s, when Hollywood was competing with television

by doing something which television couldn’t do, with those

gigantic screens. Like in The Ten Commandments, there’s

a giant thing of Pharaoh, a giant sculpture. It starts at one

end of the screen and you watch it go to the other end of the

screen. Phenomenal. Lawrence of Arabia, oh my God, the dunes of

Lawrence of Arabia with that music.

There’s

no sense of the large. Young people have no sense whatever of

the expansive, of the big gesture.

COWEN:

But do we maybe overrate the large? If the large gave through

so quickly, so readily, to what you’re describing as this

kind of mediocrity, what was wrong with that culture of the ’50s,

’60s, and ’70s to begin with?

PAGLIA:

I would say that a culture always moves in cycles. You have periods

that esteem the colossal, like the Bernini Renaissance and Baroque

periods. Then you get the small, the art of the small. The Rococo

is a kind of evanescence, evaporation of the big Baroque swirls.

All of a sudden it’s little tiny things like on a Valentine’s

card.

I think

we go back and forth. I just feel lucky, I think, that I have

a kind of epic imagination, because I was raised watching The

Ten Commandments and Ben-Hur, which I could watch that 300 times.

COWEN:

It’s one of your 10 favourite movies, right?

PAGLIA:

Yes.

COWEN:

It’s the one on the list that’s surprising.

PAGLIA:

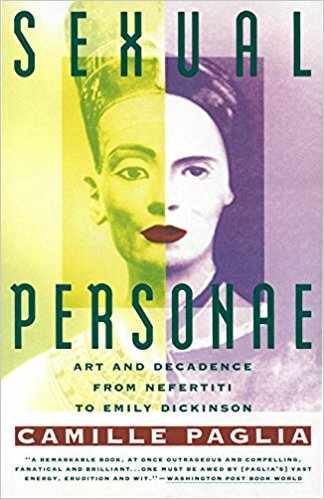

Torment. And the music composed for those things. It directly

inspired my writing of Sexual Personae, absolutely. I’m

directly inspired by music. I think for women it’s good

to have something that’s going to make you assert and trample

and conquer. It animates me. These are my maxims.

COWEN:

Given what you’re saying, do you today consider yourself

a cultural conservative?

PAGLIA:

No, not at all.

COWEN:

Why not? Everything used to be better. Isn’t that?

PAGLIA:

No, we’re in a period of decadence, a falling off, you see.

No, conservative would mean that I would be cleaving to something

past, which was great, and no longer is, and I would be saying,

“We need to return to that.” Usually I’m not

saying we need to return to anything. I do believe we’re

moving inexorably into the future. There’s a momentum to

that. I’m a libertarian. That’s why I’m always

freely offending both sides.

PAGLIA:

Liberal, conservative. I’m a Democrat, even though I’m

constantly criticizing -- I think a true intellectual should be

always beyond partisanship.

COWEN:

And always criticizing.

PAGLIA:

Yes, and always critiquing the premises of your own friends and

allies.

COWEN:

Brazil. You mentioned you’ve been there nine times?

PAGLIA:

Yes. Nine or ten.

COWEN:

What does Brazilian culture have which North American culture

lacks? What’s the draw?

PAGLIA:

It’s such a polyglot of cultures and ethnicities. But beyond

that, Brazilians understood my work from the first moment I began

to publish. Because what they understood was artifice, art --

because of Carnival for them, and costuming, masquerade, and that

baroque exuberance, and the syncretism of Christianity with the

Yoruba cults of West Africa in Salvador de Bahia.

They

understood my vision of art and beauty -- and beauty as an incredibly

important human principle, rather than the way it was being trashed

by my fellow feminists at that time.

They

also understand nature, the grandeur of nature, the power of nature.

It’s much larger.

COWEN:

Iguaçu?

PAGLIA:

Yes, instead of these silly little arguments that, “Oh,

climate change is causing the end of the world.” Oh my God.

Anyone who talks like that does not understand the grandeur and

the power of nature. To imagine that we can make a change in it

is so absolutely absurd.

COWEN:

What’s your theory of modernity that puts them on one part

of the curve, and we’re on another, more decadent part of

the curve? What’s the difference? What’s what we would

call the structural equilibrium as economists, if I dare invoke

such a thing?

PAGLIA:

Brazil, it’s in its own world. It’s not been part

of the world wars. It doesn’t have this huge militaristic

superstructure. It doesn’t have a messianic view of itself

politically. The politics are always chaos and drama. It’s

like in grand opera. It’s like another planet, really, Brazil.

COWEN:

You’ve spoken very highly of the prequels, which many people

don’t like at all.

PAGLIA:

Yes.

COWEN:

What is it that people don’t get about the prequels? They

say Jar Jar Binks, and they scream, and they run away.

PAGLIA:

I can’t tell you.

COWEN:

Clutching their head.

PAGLIA:

I know exactly what they’re talking about.

COWEN:

Tell us what’s good about the prequels?

PAGLIA:

It was Revenge of the Sith -- after the great volcano planet climax

of Revenge of the Sith. I think it’s one of the greatest

sequences in all of modern art. The thing is once I had written

about it, I realized, as I went out in the world, how few people

had actually seen the movie, because people had given up on the

prequels long before.

Therefore,

I think anyone who dismisses what I say about the sublime quality,

the vision, the execution, the emotions, and the passions of that

scene, they don’t know what I’m talking about, because

they haven’t exposed themselves to it.

COWEN:

You wrote about the Rolling Stones some time ago, but if I look

at the career of the Stones — they have a new album coming

out this year?—?I find it striking that they’ve kept

on going. And I actually count that as a mark against them.

I still

think they’re good, but when I go back and listen, I never

hear new things in their music. Now that some time has passed,

what would you say about the Rolling Stones, and do you agree

that you’re a little disappointed with them?

PAGLIA:

I haven’t been following them for many, many years. To me,

the Rolling Stones were a revolution when they happened, in that

period when the Beatles were all upbeat. Then, here come these

surly guys sneering, and spitting, and so on.

COWEN:

But the Beatles were dark and subtle, too, right?

PAGLIA:

Not like the Stones. Here’s the difference. The Rolling

Stones are inspired by, animated by, to this day, by the blues

tradition. The Beatles really were more almost Broadway and musical

comedy.

COWEN:

British music hall.

PAGLIA:

Yes, British music hall and Tin Pan Alley, and so on. They were

tremendous songsmiths, but there’s nothing dark about them.

In other words, Paul McCartney is a wonderful bass player, but

you’re not getting the big, roaring sounds of Bill Wyman’s

bass at the beginning of the Stones’ career.

I really

have not been following the Stones. Ever since Bill Wyman left

the Stones, I have not felt that this was the Stones I knew. I’m

delighted that they go on, and that they perform, and so on, but

I have absolutely no interest in exposing myself to those horrible

arena conditions for music. Oh my goodness, just the light shows

and the this and the that. They’re not musical experiences.

They’re social experiences now.

COWEN:

What’s the music from classic rock that when you listen

to it today, every single time you hear more in it? I would say

Brian Wilson and Jimi Hendrix. Every time I hear them, it sounds

different and fresher for me. What are your picks?

PAGLIA:

Jimi Hendrix is one of the great geniuses of any instrument in

the last a hundred years. Obviously, his music has lasted and

is still fresh. For me, there’s a whole period there I teach

in my Art of Song Lyrics course. I just was doing Crosby, Stills

& Nash, “Wooden Ships,” and it still has this

incredible power.

I love

that entire period of the 1960s, the music. It was a magic moment.

Still in the ’70s, Led Zeppelin, “When the Levee Breaks.”

It still has enormous power. A lot of that music that Jimmy Page

was doing. A lot of it working in the studio, actually. It wasn’t

just live music.

COWEN:

Fast-forward back to the present. Who would be a musical artist

today? i know you’ve written Taylor Swift is a pestilence,

so it’s probably not her.

PAGLIA:

Taylor Swift is like a nightmare.

COWEN:

Who would be the musical artist today who stands up to the giants

of the past?

PAGLIA:

Stands up working today?

COWEN:

Working today or close to today. The last 10 years.

PAGLIA:

I was really very hopeful about Rihanna for a while there. Unfortunately,

she’s not really working with the top producers any longer.

The new album is an atrocity. It’s really terrible. It’s

sad, because there are so many people with talents who are not

being developed.

PAGLIA:

I was really very hopeful about Rihanna for a while there. Unfortunately,

she’s not really working with the top producers any longer.

The new album is an atrocity. It’s really terrible. It’s

sad, because there are so many people with talents who are not

being developed.

It’s

because our music industry is now very formulaic. Young people

can’t really move along studying their instruments and getting

their chops over a period of time. There’s nothing to draw

on in the way that the musicians of my generation could draw on

the folk tradition, the folk music.

COWEN:

You’re sounding like a cultural conservative.

PAGLIA:

I’m just saying there’s certain moments, certain magic

moments, of fertility or creativity that happened in many of the

arts. You can find certain key moments where there’s a confluence

of influences and a certain richness. In that very moment, it’s

a great time to be alive, to be young.

For example,

Shakespeare would not be Shakespeare if he were alive today. As

it happens, he left Stratford -- for whatever reason -- went to

London at a magic moment when theater was flourishing, which was

only for a few decades, and then it was out again. There’s

a certain kind of luck. If you’re the right person at the

right time in any one of the artistic genres.

COWEN:

Kanye West. Every album is different. He draws upon a lot of sources

from the past.

PAGLIA:

Oh my God. The bloat.

COWEN:

Inspired by rap, rhythm and blues, no?

PAGLIA:

What can I say?

COWEN:

On education, there’s a new model school called Minerva,

where you take four years, you spend each of the four years in

a foreign country. One year in Buenos Aires, one in Istanbul,

one in Bangalore.

You work

in small classes, but the classes are all online. There’s

no library. There’s no formal campus, per se. It’s

been around for about two years. What do you think? What’s

your prediction?

PAGLIA:

I think the idea of sending young people abroad is great. I think

that is a proper use of the money that’s going down the

tubes at the major universities right now. For parents to think

-- it would profit young people a lot to be exposed to the world.

Right now, our primary school education is absolutely appalling

in its lack of world history and world geography.

I know

because I get everyone in my classroom. I’m lucky I teach

at a kind of school where I’m getting students from a wide

range of preparation. There might be a couple private school people,

but people from the inner city, from good schools, from bad schools.

I really have a very clear sense, after 40 years of teaching,

what’s going on at the primary school level.

It is

unbelievable how little they know. It is absolutely shocking how

little they know. This is a recipe for a disaster. I say yes,

send them abroad. Fantastic idea.

This

other thing of the online thing, I don’t believe this online

thing at all. I think that you need a live person, and you need

a live person who can talk extemporaneously and respond to the

moment. Not just people who are reading the same old damn lecture

over and over again.

Also,

the kind of teaching that goes on in the Ivy League where there’s

a flattering. There’s these small seminar things.

COWEN:

The A-minus seminar?

PAGLIA:

There’s all this practice and learning how to talk in a

slightly pretentious way about things and impressing each other.

So what? They’re all packaging them for the bourgeoisie.

COWEN:

Send them to Brazil, right?

PAGLIA:

They’re so proud of themselves as they produce all these

clones, these polished, bourgeois clones, witless, knowing nothing.

COWEN:

Speaking of inspiring teachers, what’s your favourite Harold

Bloom story -- that you can tell?

PAGLIA:

I never took a course with Harold Bloom. I was in graduate school

at Yale, and I just never took a course with him, so I didn’t

know him at all. And then he heard -- one time I encountered him

-- I shouldn’t say this. OK, maybe. Let’s say he would

come a-courting with a famous poet, who was a friend of his.

PAGLIA:

I never took a course with Harold Bloom. I was in graduate school

at Yale, and I just never took a course with him, so I didn’t

know him at all. And then he heard -- one time I encountered him

-- I shouldn’t say this. OK, maybe. Let’s say he would

come a-courting with a famous poet, who was a friend of his.

I would

see him turning up at a doorway. “Hello, hello, hello,”

OK, that’s all. I just knew him to say hello to him. Then,

he heard what I was going to be working on and that I was having

trouble finding a dissertation director for a study of androgyny

in literature and art.

That’s

a time when nobody was doing -- it’s hard to believe now

because everything is sex and gender everywhere -- but at the

time, no one was doing a dissertation on sex at the Yale Graduate

School. It’s hard to believe. He summoned me to his office.

That’s really how we met. He said, “My dear, I am

the only one who can direct that dissertation,” and I said,

“OK.” That was it.

He understood

everything. He understood everything I wanted to do with the book,

and he understood my ideas. He was a fantastic resource for me

in so far as he also supported me or gave me confidence throughout

all those decades when I couldn’t get it published. Sexual

Personae was rejected by seven publishers and five agents.

By the

time it was published, I was 43 years old. I’m a great role

model, it seems to me, for people to just soldier through adversity

and rejection and just continue to develop the craft. Eventually,

hopefully, one will see one’s work in print.

COWEN:

What did he think of you and Sexual Personae?

PAGLIA:

Of course, he always said I gave him great naches, which is sort

of like of a father to a daughter. He and I agree about Freud.

We have a Freudian psychohistory and so on.

COWEN:

There’s a segment of all of these conversations in the middle.

It’s called underrated or overrated. I mention something,

and you tell me if you think it’s underrated or overrated

by our society.

PAGLIA:

By our society or by me?

COWEN:

Your opinion relative to the society opinion. Now, don’t

hold back on these. Tell us what you think.

COWEN:

First one, economics.

PAGLIA:

Economics as a field?

COWEN:

As a field. Overrated or underrated?

PAGLIA:

Probably underrated.

COWEN:

Why?

PAGLIA:

I don’t know. I just think that economists are figures of

fun sometimes in cartoons. I’m just judging by what I sense.

COWEN:

William Faulkner.

PAGLIA:

He’s totally gone, poor man. Actually, I’ve been commenting

on this recently to my friends. I said, “You remember that

period when Faulkner was everywhere, and everyone read him? He

was just a baseline figure.”

Thanks

to Kate Millett and all these philistine feminist types in the

early ’70s, there was a great sweeping away of many, many

major male figures in the history of literature including Ernest

Hemingway, D. H. Lawrence, who had a huge influence on me.

If you

are a resident of Mississippi, Faulkner still lives and is vivid.

I think, outside of that, it’s been years since I’ve

heard Faulkner mentioned.

COWEN:

You’re saying underrated?

PAGLIA:

I think he should be on the reading list. I don’t know.

Perhaps he was overrated in our time, but he certainly was a major

author and a major influence on American literature, for heaven’s

sake. Young people aren’t reading him, and they aren’t

reading many of the great authors.

COWEN:

Yoko Ono, overrated or underrated?

PAGLIA:

Yoko Ono, don’t start me on Yoko Ono. One of my least favourite

people in the universe. Yes, I blame her for the breakup of the

Beatles. All that screechy yodeling that went on. Oh my God, she’s

a horror. But, I gave her her due in Glittering Images, because

she was a very important figure in the development of conceptual

art. She really was very innovative in the 1960s, but what a dreary,

humourless person.

COWEN:

When I think of a lot of your books, especially if I contrast

you to Marxist criticism, I think of your emphasis as being a

lot of metaphysics in a very exciting, big-picture way. Let’s

say we take a writer, very high quality, but she moves very far

from metaphysics. She writes about small numbers of people in

rural Ontario, Alice Munro.

PAGLIA:

Oh, I don’t read fiction. I don’t read contemporary

fiction. I have absolutely zero interest in contemporary fiction.

The last contemporary fiction I had any interest in is Auntie

Mame, and I’m not kidding. I like plays like Tennessee Williams.

The fiction

writers are off in another world. They don’t see the world

as it exists now. They don’t use the language of the contemporary

world. Their English is utterly stale and cloistered. I cannot

read a page of contemporary fiction, I’m sorry. Anything

that’s pre–contemporary fiction, I’m a great

admirer of. Believe me, these are the kind of books I’ll

open like this and like that. .

COWEN:

You’re going to pass on Harry Potter, too?

PAGLIA:

Harry Potter, no, I don’t. In fact, I refused to write on

Harry Potter for the Wall Street Journal once. They said,

“Who should we ask next?” and they asked Harold Bloom.

Harold Bloom became known for it. He got that because of me. Just

like Norman Mailer got to interview Madonna for the cover of Esquire

because Madonna said no to me.

People

kept trying to bring us together. HBO wanted to do a My Dinner

with Andre type of thing with Madonna and me, and she was afraid.

I don’t know. I think she thought I was going to be some

big intellectual, but it’s not true.

COWEN:

Parenthood, underrated or overrated?

PAGLIA:

Parenthood? Obviously, we’re in a time now where parenting

is in crisis, I would think. The reason we have all these whiny,

super sensitive girls on campus that’ll run shrieking at

the slightest thing that offends their ears or drag mattresses

onto the stage at commencement exercises, the reason we have that

is because the parents have not prepared them for real life.

In other

words, they’ve been raised in this bourgeois, pampered cocoon,

so I think there’s been a tremendous failure of parenting,

certainly, in terms of young people being ready to take on the

real world in their late teens.

COWEN:

What’s the most underrated play by William Shakespeare?

PAGLIA:

The most underrated play?

COWEN:

Yes.

PAGLIA:

I don’t know. I really can’t answer that. I’m

teaching my Shakespeare course this semester. I simply focus on

the really major plays. Perhaps Antony and Cleopatra

is starting to recede. I don’t know why.

I think

Antony and Cleopatra was a great favourite of my generation,

of the ’60s generation, but, for some reason, it’s

becoming marginal. I’m not sure. Maybe because it’s

about imperialism.

COWEN:

May I ask a few questions about sex?

PAGLIA:

Of course.

COWEN:

Which country comes closest to your vision of having healthy relations

between the sexes? Or among the sexes, which may be a better way

to put it.

PAGLIA:

I would say that Brazil has the healthiest view of sexuality,

but I wouldn’t say that the sexes are particularly getting

along in the upper middle class in Brazil, as I meet professional

women, journalists and so on, there.

I think

that the women are magnificent. They’re incredible, the

way they look and dress. They have such style, and assertiveness,

and so on, but I’m not sure the communications with men

are particularly successful right now. There’s a lot of

static there. The men are like gnomes. It’s strange. They

don’t have this thing. In the United States, usually the

upper middle class, successful careers and so on, you have the

women doing their Pilates, and then the men will be going to the

gym also. Not in Brazil. The men just seem to sag and get plumper

and plumper, and duller and duller, and lose their hair and nobody

minds.

I think

because they assume that woman rules. Woman is the cock of the

walk down there. I’m still trying to figure it out. Anyway,

I love it. I adore it. I love Brazilian women. They’re so

bossy.

COWEN:

We’ve now had gay men in the military for some time out

openly, legally, permissible. How that has run, has it surprised

you? Earlier you wrote you expected it could be quite disruptive,

and it hasn’t been. In a sense, has male gay culture turned

out to be tamer than what you expected in the early ’90s?

PAGLIA:

Tamer?

COWEN:

Tamer. More domestic. More people adopting children, more people

settling down.

PAGLIA:

It’s changed. There’s no doubt about it. I think that

AIDS was like a Holocaust. The number of interesting, fascinating,

talented men and artists and people in fashion and every level.

I think that, in many ways, gay culture is still recovering from

that. We’re at a kind of holding pattern.

There

was an enormous flamboyance and assertiveness to gay male culture

once. It had a distinct style and voice of its own. What you’re

saying, things are turning out better. Yes, there’s an assimilation

going on, but also, to me, a disappearance of that gay aesthetic.

Oscar

Wilde is one of the major influences on my thinking and remains

that. I teach a whole course on Oscar Wilde. Now, what can you

say? Is there anything distinctly gay right now, except there

are certainly gay activists who are extremely successful in terms

of pushing their agenda. Probably these little cadres of gay activists

are the only thing that’s left.

I don’t

know. Assimilation is always a loss. Certainly, my culture experienced

it. Italian-American culture has kind of vanished, too.

COWEN:

For America, what should an ideal of masculinity look like now?

PAGLIA:

What should it look like? I don’t know.

COWEN:

An older generation, you would have a Cary Grant or a Rock Hudson.

You would see the movie Philadelphia Story, one of your favourites.

There was some ideal of masculinity on the screen, maybe not your

ideal. Today, what is it that’s out there which comes closest

to your ideal?

PAGLIA:

Well you know many of those images on the screen which would seem

to be masculine, often the actual actors were gay, like Rock Hudson

-- and Cary Grant’s sexuality remains one of the great mysteries.

I adore Cary Grant, oh my God, but he’s like a hallucination.

All of the great images on the screen are hallucinations. Kim

Novak in Vertigo is literally a hallucination.

The problem

right now is that the masculine has no honour whatever in our

culture. We’re in a period now where young people are being

processed for the universities, and the gender norms are said

to be that gender is a construct. It is simply the product of

environmental pressures on people. There’s no nothing in

the body -- .

COWEN:

We have a big culture. Not everyone goes to university, thank

goodness. You can go to a NASCAR race and a few of the people

there have not been to the Ivy Leagues.

PAGLIA:

Working class culture retains an idea of the masculine. There’s

absolutely no doubt about that. But, with that, comes static.

So you have to have strong women in order to deal with masculine

men.

That

is why masculinity is constantly being eroded, diminished, and

dissolved on university campuses because it allows women to be

weak. If you have weak men, then you can have weak women. That’s

what we have. Our university system, anything that is remotely

masculine is identified as toxic, as intrinsic to rape culture.

A utopian future is imagined where there are no men. We’re

all genderless mannequins.

The movie

The Time Machine is like one. We’re moving toward that,

the Eloi. That’s how I see the upper middle class graduates

of the Ivy League. They’re the Eloi. They’re completely

bland. They have no ideas. They all get along very well with each

other because they’re nothing. They’re eating their

fruits which are given to them by the Morlocks, or the industrial

class. That’s how I see the future? -- ?unfortunately. I

began my career talking about androgyny and talking about the

imaginative complexity of androgyny and how the artist and the

shaman and the prophet have this androgynous component. But today’s

androgyny, it’s just boring.

David

Bowie, at his height, was absolutely brilliant, electrifying,

kabuki -- on and on and so on. Now, all these pallid androgynes

of today, there’s nothing creative about them whatever.

COWEN:

But to try to cheer you up a bit, what then is the healthiest

segment of American society? Because, again, you’ve lived

most of your life in the northeast, mostly in colleges and universities,

correct?

PAGLIA:

Yes.

COWEN:

Think outside the box. Where do you see vitality, both culturally,

sexually in terms of aesthetics?

PAGLIA:

No, I don’t. I think it’s been a tremendous flattening.

There’s very little culturally right now. There’s

very little of substance or interest being produced in art and

in culture. We’re in a retro period. We’re chopping

up everything, putting everything from the past through the grinder

again.

COWEN:

How about Canada? Overrated or underrated? Or, do they have all

the same problems?

PAGLIA:

Canada, they have this ideal of the consensus. That’s why

when I go up there, people have said to me actually quietly, “Oh,

I love having you here, because everyone’s always forcing

us to have consensus in Canada.”

I’ve

been told that also when I go to Norway. People say, “Oh,

we can’t stand it. We are not allowed to have an opinion

in Norway. We all have to have a consensus.” Everyone is

very civilized in Canada, but it’s impossible to rise above

the herd, also. You can’t make any big gestures; you’re

thought to be antisocial. I wouldn’t glorify Canada.

COWEN:

Let me ask you a few questions about yourself. There’s a

wonderful four-page essay you wrote called “The Artistic

Dynamics of ‘Revival’,” where you talked about

how creators have early, middle and late periods.

Beethoven

is maybe the most obvious example, but there are many, many others.

When you think of your own career, how do you see it as fitting

together in terms of a time arc, what you’ve done and what

you want to do? What are your early, middle, and late periods?

Where are you in it now?

PAGLIA:

My early period was total failure, flop, and in the middle to

get published. There was that. Then, all of a sudden, I started

to burst out, like a jack-in-the-box. It’s been like blabber,

blabber, blabber ever since. Like that. I really don’t see

phases. I see like nothingness, then everything. It’s like

a carnival.

COWEN:

What will the late period look like?

PAGLIA:

The late period?

COWEN:

We haven’t gotten to it, yet. The everything is the middle

period.

PAGLIA:

Right now, I’m working on something that no one has any

interest in, whatever. I’ve been working for eight years

on this, my Native American explorations. I’m very interested

in Native American culture at the end of the ice age as the glacier

withdrew.

I go

around and I find little tiny artifacts. I read. Absolutely no

one, especially anyone in Manhattan, has the slightest interest

in what I’m doing. Everything has been prepared for in my

life. I’ve always been interested in archeology. I feel

like I make a contribution, even though no one’s interested

at all. What I’m trying to do is show how the politicization

of ethnic studies, of racial studies, and so on has actually been

very limiting.

I find

very objectionable this eternal projection of genocide and disaster

and so on onto Native American studies. I’d like to show

the actual vision of Native American culture which is a religious

vision, a metaphysical vision, and -- .

COWEN:

Cyclical approach?

PAGLIA:

Cyclical?

COWEN:

Relevance of nature.

PAGLIA:

Yes, totally.

COWEN:

Metaphysics epicenter.

PAGLIA:

It’s almost like an early animism. That’s why I’m

interested in Salvador de Bahia, also, because of the Yoruba cults

of West Africa that were absorbed into Salvador de Bahia in Brazil.

It’s the same, where all of the forces of nature are perceived

as spirit entities that can bring you energy or vision.

COWEN:

Of the Native America cultures which have come down to us, which

is different, of course, from what you had at the Ice Age, which

of those do you relate to the most and why?

PAGLIA:

All I’m doing is exploring the Native American cultures

of the northeast. Because when the settlers came from Europe,

the Indians were pushed out, the hunting grounds were limited,

then there was general destruction of Native American culture

for many reasons during that period.

We know

more actually about the Plains Indians and, obviously, Northwestern

Indians, and the Navaho than we do about the Northeastern Indians.

I believe that there are remnants everywhere -- I stumbled on

this. I’m very sorry I didn’t notice this when I was

living all those years in Upstate New York, where the Onondagas

still have their reservation. Probably the remnants of these glacial

era cultures were still there as well.

But I

find it’s absolutely staggering. It is staggering the actual

signs and remnants that are everywhere in the Northeast. I could

go out right now, find some dirt, and I’ll find you a broken

tool. It’s absolutely incredible. I feel that’s what

I should be doing something like this, which no one is interested

in. But I feel it’s substantive, and I hope can help to

show what was here before.

COWEN:

In Vamps & Tramps, you once wrote that as early as

1981, the second volume of Sexual Personae was more --

finished is a tricky word we know as writers. But some version

is finished, and do you think we will . . . ?.

PAGLIA:

It was finished. Yale Press didn’t want to publish those

last chapters.

COWEN:

I’ll publish it.

PAGLIA:

Yale Press ended with the end of the 19th century with Emily Dickinson

and it was already a 700-page book. Yes, I put in there the next

book was coming. Then what happened, of course, is throughout

the ’90s, and since the last 25 years, I’ve been essentially

writing in articles everything that I would have written in that

sense.

All my

writing on popular culture, I’ve continued to do. Like on

football, I had a chapter, “Baseball versus Football,”

and football is the ultimate pagan sport, etc.

Well

I wrote for Wall Street Journal, my football feminism.

I have a whole concept and philosophy of that. Now, football is

getting more and more boring. It’s gotten more and more

technocratic. It’s not in a period right now that I would

celebrate.

But I

was celebrating that tremendous period when there were still hard

hits and there was still defense. There wasn’t all this

throwing, flinging the ball down the field, people catching it

like ballerinas. Please, that’s not football. Football is

wham, like that. The TV won’t show the great defensive plays.

The whole art of defense, the great offensive, defensive lines,

and that tussle, it’s gone. I feel lucky that I saw football

on TV at its high point.

COWEN:

You also wrote that when you were in high school, you either wrote

or just started a book on Amelia Earhart. What was the appeal

of her to you?

PAGLIA:

Oh my God. Amelia Earhart, I stumbled on. It was an article in

1961 in the Syracuse Herald Journal. There was always some article

about Amelia Earhart. Someone finds a fragment or something.

I became

very interested in her. At that point, I was, I guess, 14. I began

researching her in the bowels of the Syracuse Library, the things

were still not on microfilm yet. All the newspapers were still

there from the 1930s.

I did

that for three years on this research project. That’s how

I became a feminist before feminism had revived, because I suddenly

discovered this period just after women had won the right to vote.

In the 1920s and ’30s, we had all these career women, like

Amelia Earhart, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Thompson, Clare Boothe

Luce. There’s so many women, Margaret Bourke-White.

By the

time second-wave feminism revived, which was with Betty Friedan’s

cofounding of NOW in 1967, I was out of sync with them. When suddenly

they revived, began complaining about men, and all that stuff,

so on and so forth, I hated it. It was early clashes that I had

with those feminists from the start. I tried to join second-wave

feminism. They wouldn’t have me because I would not bad

mouth men.

These

women, like Amelia Earhart, they did not bad mouth men. They admired

men. They admired what men had done. What they said was, “We

demand equal opportunity for women,” which gave us the opportunity

to show that we can achieve at the same level as men who did all

these great things.

That

was not the tone of second-wave feminism from the start. It’s

almost like, “Patriarchy?. ” [makes sounds] like this.

These women were insane. I found out from the start. I went to

this feminist conference at the Yale Law School when I was in

graduate school. It was 1971. Kate Millett was there. Rita Mae

Brown who later became a lesbian novelist and lives on a horse

farm in Virginia came around.

COWEN:

Maybe she’s here.

PAGLIA:

Maybe she’s here. She’s very rich. At any rate, Rita

Mae Brown said to me, she said, “The difference between

you and me, Camille, is that you want to save the universities,

and I want to burn them down.” What can you say? What a

conversation stopper. I had the knock down argument of the Rolling

Stones with the New Haven Women’s Liberation Rock Band.

I adore the Stones. They hated the Stones. We had this huge screaming

argument. My back was to the wall. They were screaming in my face.

I said, “Yes, the Rolling Stones are sexist, but they made

great music.” They go, “Oh, no, no, no!”

I said,

“All right, let’s take “Under My Thumb,”

yes, it’s sexist, but it’s a great song. It’s

a work of art.” These women, they said to me, they said,

“Art! Art! Nothing that demeans women can be art!”

Now that is a Stalinist view of art!

COWEN:

More about you. Less about them.

PAGLIA:

Wait a minute. Then there was the argument that I had. This is

about Amelia Earhart. Then I had my first job at Bennington College

in 1972. People said, “There’s this new women’s

studies department. One of the first ever at the State University

of New York at Albany. Oh, you’ll be one of them.”

I thought,

“Well, they’re feminist. I’m feminist. OK. All

right.” We had a dinner. We were going to go to a lecture,

and so on. We didn’t get through to dessert. Let me tell

you about that dinner. Because we had this screaming argument

about hormones.

They

deny that hormones have the slightest impact on human life. They

said hormones don’t even exist. They told me I had been

brainwashed by male scientists to believe -- these are women who

are in the English department. Wonderful education they had in

biology. At any rate, Amelia Earhart —.

Never

was like this with men. This is the point. In fact, my next book,

my next essay collection, I’m going to reproduce the page

from Newsweek magazine, 1963, I wrote in a letter to the editor.

It was their number one letter. I was 16 years old, at that point.

What

was it? They put a picture of Amelia Earhart there. It was Valentina

Tereshkova had become the first women in space. The Soviet Union

had sent her up. I wrote a protest letter into Newsweek and I

said, “That Valentina Tereshkova, the cosmonaut, has became

the first woman to be? -- ?on the anniversary that Amelia Earhart

flew the ocean,” whatever it was. It was some big anniversary.

I said,

“Obviously, Amelia Earhart’s lifelong fight for equal

opportunity for American women remains to be won.” That’s

1963. Gloria Steinem can lick dirt, as far as I’m concerned.

When I was doing that, Gloria Steinem was running around New York

in a plastic skirt, I’m telling you. She’s a fraud,

that woman. A fraud.

END OF

PART I