a semantic perspective.

SEXUAL HARASSMENT

by

HOWARD RICHLER

___________________________

Howard

Richler is a Montreal-area word nerd and author of these seven

books on a variety of language themes: Dead Sea Scroll Palindromes,

Take My Words, A Bawdy Language, Global Mother Tongue, Can I

Have a Word With You?, Strange Bedfellows and his most

recent book Wordplay:

Arranged and Deranged Wit ( May 2016, Ronsdale

Press, Vancouver).

Alas, the year 2017 was marked by words that denote

the ill-treatment of women by men. Following the revelations of

the behaviour of Harvey Weinstein and his predatory ilk, the adjective

‘inappropriate’ saw a large spike in usage. People

soon realized that this word, often applied to the misbehaviour

of a child, wasn’t quite suitable to describe the level

of misdeeds. Before long stronger terms such as ‘abuse’

and ‘harassment’ became the most common used descriptions.

And if one considers it as a word, the hashtag #MeToo became a

rallying cry from many women to describe their own similar experiences

of sexual harassment.

Underscoring

this lexical recognition of the plight of women, Merriam-Webster

named the word ‘feminism’ as its word of the year

for 2017 and stated that it was the most searched-for-word in

its online dictionary, showing a 70% increase from 2016. Also,

the word ‘persisterhood,’ defined as women who join

forces to persist against sexism and gender bias, was nominated

as one of the words of the year of 2017 by the American Dialect

Society. (The winner was ‘fake news.’) Also,

highlighting how the issue of sexual harassment marked 2017, Time

magazine declared that its ‘person of the year’

were the Silence

Breakers: The Voices that Launched a Movement.

The magazine’s cover featured Ashley

Judd, Susan Fowler, Adama Iwu, Taylor Swift, and

Isabel Pascual who were among the many women who went public in

describing their painful encounters with sexual predation.

Underscoring

this lexical recognition of the plight of women, Merriam-Webster

named the word ‘feminism’ as its word of the year

for 2017 and stated that it was the most searched-for-word in

its online dictionary, showing a 70% increase from 2016. Also,

the word ‘persisterhood,’ defined as women who join

forces to persist against sexism and gender bias, was nominated

as one of the words of the year of 2017 by the American Dialect

Society. (The winner was ‘fake news.’) Also,

highlighting how the issue of sexual harassment marked 2017, Time

magazine declared that its ‘person of the year’

were the Silence

Breakers: The Voices that Launched a Movement.

The magazine’s cover featured Ashley

Judd, Susan Fowler, Adama Iwu, Taylor Swift, and

Isabel Pascual who were among the many women who went public in

describing their painful encounters with sexual predation.

Writing

in 1991, Rosalie Maggio in the Dictionary of Bias-Free Usage

remarked that “sexual harassment was not a term anyone used

20 years ago; today we have laws against it.” Actually,

it was exactly twenty years earlier that we find the first citation

of sexual harassment in the OED, and it comes from the

Yale Daily News of April 19, 1971: “We insist . . .

that sexual harassment is an integral component of discrimination.

Men perceive women in sexual categories and not in professional

categories.”

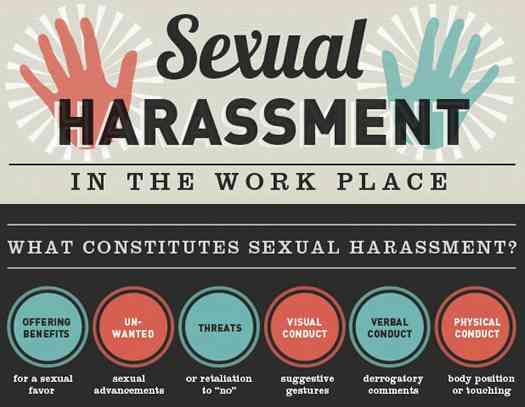

The OED defines the term as “harassment (typically

of a woman by a man) in a work place or other

professional or social situations involving the making of unwanted

sexual advances obscene remarks, etc.” Maggio’s point

was that while sexual harassment obviously occurred prior to 1971,

its lexical recognition gave it greater force to be countered

by laws or social norms. Before long sexual harassment was recognized

as a phenomenon in the legal arena. In 1986, the Supreme Court

of the United States ruled that employers could not permit an

employee to create a hostile work environment for someone else

or base advancement on a quid pro quo for sex. In 1989,

the Supreme Court in Canada ordained that sexual harassment represented

sexual discrimination and thus could not be tolerated.

Most

academic institutions have definitions of sexual harassment and

invariably they contain hard to define adjectives such as ‘unwanted,’

‘unwelcome,’ ‘vexatious’ and ‘obscene.’

Adjectives by definition are descriptive and depend largely on

a consensus of a shared reality which unfortunately does not exist

in analyzing sexual harassment. For what is deemed unwanted or

unwelcome by one person may be wanted or welcome to another. Also,

what qualifies as an obscene comment or joke can be highly subjective.

One definition of sexual harassment includes the phrase “verbal

or physical conduct of a sexual nature that tends to create a

hostile or offensive work environment.” Again, we’re

dealing with thorny adjectives such as ‘hostile’ and

‘offensive.’ Almost everyone, male or female, accepts

that sexual favours can’t be a condition for a job or promotion.

Large majorities consider unwelcome touching as improper but often

women and men disagree on what constitutes sexual harassment,

such as what counts as sexualized remarks or what qualifies ogling.’

And although younger men’s attitudes approximate those of

women to a much larger extent than older males, the gap in the

positions of the sexes endures.

It

is also important to register that there is a hierarchy of offenses

related to the term sexual harassment. When actor Matt Damon in

an interview with Peter Travers of ABC Television, stated “there’s

a difference between patting someone on the butt and rape or child

molestation, right? Both of those behaviours need to be confronted

and eradicated without question, but they shouldn’t be conflated,

right?” Those comments were met with anger and frustration

online, where many women, including the actress Alyssa Milano,

rejected attempts to categorize various forms of sexual misconduct.

After Damon’s interview, Milano wrote on Twitter: “They

are all connected to a patriarchy intertwined with normalized,

accepted -- even welcomed -- misogyny.” In a panel discussion

of seven feminists in the New York Times on sexual harassment,

broadcast journalist Soledad O’Brien came down squarely

on Damon’s side in this dispute referencing the various

meanings of the term: “I think we conflate the many different

definitions of sexual harassment -- the legal definition, someone’s

personal interpretation. Some things are legally a crime. Other

actions would clearly violate a company’s standards, inappropriate

language, physically grabbing a woman, pressuring an underling

for sex. They are all bad and should be stopped, but I think they

deserve different levels of punishment.”

Interestingly,

on some university campuses the term ‘affirmative consent’

has gained currency. It postulates that at every stage of a relationship

there should be a verbal agreement but, as Daphne Merkin points

out in a Jan 5, 2018 article in the New York Times, “asking

for oral consent before proceeding with a sexual advance seems

both innately clumsy and retrograde.” And so the debate

on what constitutes sexual harassment and how to combat it rages

on.