John

J. Curley is Associate Professor of Modern and Contemporary

Art History at Wake Forest University. This essay was adopted

from his book A

Conspiracy of Images: Andy Warhol, Gerhard Richter, and the

Art of the Cold War (Yale University Press,

2013). Other publications can be viewed at https://wfu.academia.edu/JohnCurley.

This article was originally @OUPblog.

Birthdays

are complicated. They are cause for celebration but also remind

us that we are closer to death. Such duality would not have

been lost on Andy Warhol (1928-1987), an artist who strove throughout

his career to find images that could house such contradictory

notions. These mutual feelings of jubilation and morbidity would

have become especially apparent on Andy Warhol’s seventeenth

birthday on 6 August 1945, when the United States dropped a

nuclear bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. For the rest of his life,

Warhol shared his own birthday with the birth of the nuclear

age and the recognition of the potential for a human-engineered

global apocalypse. As the Cold War battle between the United

States and the Soviet Union heated up in the 1950s and early

1960s, fears of nuclear apocalypse became especially acute.

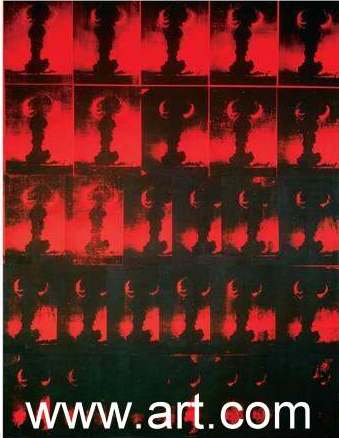

While

Warhol directly referenced nuclear weapons in a number of works

throughout his career -- most memorably in Red Explosion

from 1963, with over thirty silkscreen images of an atomic test

blast -- his most interesting explorations of the subject are

those that tackle the subject obliquely, even covertly. With

its deadpan, repeated depictions of one of the most basic American

consumer goods, 32

Campbell’s Soup Cans from 1962 is

just such a work. The work harbours a sense of existential dread

just beneath its banal surface, simultaneously blocking and

calling to mind disaster, specifically Cold War apocalypse.

While

Warhol directly referenced nuclear weapons in a number of works

throughout his career -- most memorably in Red Explosion

from 1963, with over thirty silkscreen images of an atomic test

blast -- his most interesting explorations of the subject are

those that tackle the subject obliquely, even covertly. With

its deadpan, repeated depictions of one of the most basic American

consumer goods, 32

Campbell’s Soup Cans from 1962 is

just such a work. The work harbours a sense of existential dread

just beneath its banal surface, simultaneously blocking and

calling to mind disaster, specifically Cold War apocalypse.

To

understand how a can of soup is able to convey terror, we must

consider Warhol’s early commercial art experience. After

graduating from Carnegie Tech in 1948 with a degree in Pictorial

Design, he moved to New York. Warhol soon became a highly successful

illustrator, valued for his drawings for record covers, magazine

articles, and, most of all, advertisements. For instance, in

1955 he was hired to reinvigorate the image of I. Miller, an

upscale woman’s footwear company. Warhol’s drawn

advertisements appeared regularly in the New York Times

until 1957, each one thus visible to millions of readers. On

the whole, these ads appeared in the Sunday edition of the paper,

beneath the announcements of high society engagements and weddings.

With the wealthy brides helping to elevate the status of his

drawn shoes, the surrounding context for these drawings was

thus fundamental for their meaning and commercial impact. With

these repeated appearances in the same section of the newspaper,

Warhol would come to understand the interdependence of advertising

and editorial content -- how they work in tandem. And such lessons

from commercial art would continue to inform Warhol’s

work once he decided to become a fine artist around 1960.

Returning

to 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans, the work does not

seem to harbour any feelings of atomic dread; on the contrary,

some critics have viewed the work as celebrating an iconic American

brand. And it does not look like traditional art. Around this

time, Warhol said, “I want to be a machine,” and

this work attempts to deliver on that promise. Despite being

hand-painted, the canvases are nearly identical, save for the

variety of the flavour of soup (all thirty-two varieties available

in 1962). After a decade of the macho, emotionally-laden paintings

of Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and others, Warhol wanted

to make art that avoided explicit displays of feeling. And seemingly

straightforward depictions of Campbell’s Soup cans fit

the bill.

But

the cans nevertheless were deeply integrated into the dramas

of contemporary events. At least this is the impression we get

when flipping through the widely read and highly influential

Life magazine from the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The magazine was certainly the place where Warhol, a long-time

subscriber, gained familiarity with the Campbell’s brand.

If he came to understand, through his work for I. Miller, how

advertisements could work with editorial content (fancy shoes

among fancy brides), then perhaps Life taught him the

ways that ads also worked in marked contrast with their surroundings.

As media theorist Marshall McLuhan argued in 1964: “Ads

are news. What is wrong with them is that they are always good

news. In order to balance the effect and to sell good news,

it is necessary to have a lot of bad news.” Put simply,

stories about disasters, accidents, or violent wars help the

effectiveness of advertising products like Campbell’s.

As

such, during this period, Campbell’s advertising strategy

in Life depended on purchasing the page after that

week’s lead story or opposite the all-text editorial.

Campbell’s soup cans were thus silent media witnesses

to some of the period’s biggest events, many of which

concerned Cold War tensions: there’s a Campbell’s

ad marking the end of a long article on the Soviet launch of

the Sputnik satellite in 1957; another one is next to an editorial

from 1961 entitled “We Must Win the Cold War.” And

there are scores of other similar examples. With the advertisements’

bright colours and bold graphics, readers would have been hard-pressed

to maintain their focus on the adjacent news, reported in serious

black-and-white. In such layouts, Campbell’s became the

comfort food of the Cold War -- a warm, comforting distraction

in the face of stories about death and anxiety. And the repetition

of these constructions in Life, week after week, certainly

would have transformed a can of Campbell’s soup into a

highly charged object when Warhol chose to paint it in 1962.

Perceptive early viewers of the work picked up on just these

associative qualities of Warhol; an important critic from Art

News even noted that seeing Warhol’s work inspired

thoughts of “the

soup ad in Life magazine.”

and elsewhere. Even in Kurt Vonnegut’s darkly comic novel

Cat’s Cradle from 1963, the protagonist, when faced with

the end of the world, opens a can of soup from a fallout shelter.

Campbell’s Soup was a staple of the apocalypse. Other

consumer objects during the Cold War also harboured such duality.

For instance, during the famous “Kitchen Debate”

in 1959 the American Vice President Nixon and Soviet leader

Khrushchev argued over the force of rockets and the merits of

washing machines, all the while standing in a model American

kitchen. In 1945, Warhol’s birthday was suddenly and permanently

overshadowed by a mushroom cloud, and 32 Campbell’s

Soup Cans some seventeen years later demonstrates how everyday

objects also could not escape the bomb.