AN INQUIRY INTO CONSTITUTIONAL ORIGINALISM

by

NICK CATALANO

____________________________________

Nick

Catalano is a TV writer/producer and Professor of Literature

and Music at Pace University. He reviews books and music for

several journals and is the author of Clifford

Brown: The Life and Art of the Legendary Jazz Trumpeter,

New York

Nights: Performing, Producing and Writing in Gotham

and A

New Yorker at Sea. His latest book, Tales

of a Hamptons Sailor, is now available. For Nick's

reviews, visit his website: www.nickcatalano.net

Over

2500 years ago the Greek philosopher Heraclitus averred that

"the only thing that is constant is change." Since

then Constitutionalists from democratic Athens, imperial Rome,

13th century English monarchy and Age of Enlightenment parliamentary

states have striven to create governmental frameworks that preserve

individual freedoms while protecting social order.

The

American founding fathers drew upon these frameworks and, in

1789, created a document which has become an ideal for advanced

contemporary societies that embrace democratic principles. But

they no sooner enacted these remarkable pages when they realized

that they needed amendments; thus the Bill of Rights was ratified

in 1791. Since then many other amendments have been passed as

the populace and its legislators gained knowledge of developing

personal and societal needs.

If

we focus only on the 20th century we observe many turnarounds,

evolutions and other changes. In 1917 Congress passed the 18th

amendment, ratified in January of 1919, prohibiting use of alcohol.

Then, in rebus inane, after chasing smugglers and bootleggers,

crashing tens of thousands of speakeasies, and initiating a

huge escalation in organized crime throughout the nation, the

legislators went back to the drawing board, rescinded their

mistaken thinking, finally putting to an end 15 years of chaos

dubbed the "roaring twenties." Also in 1918 Congress

caught up with European egalitarianism and passed the 19th amendment

giving women the right to vote.

It is presently

in the U.S. Supreme Court nomination process where the terms

‘originalism’ and ‘originalist’ have

been bandied about by recently elected officials who know little

about the narrowness and vacillation in key Supreme Court decisions

as the following illustrate:

In 1857, the Supreme Court enacted the infamous Dred Scott decision

known by every schoolboy, which declared that negroes were inferior

to whites -- arguably the low point in the history of the court.

This decision was overturned by the 13th and 14th amendments.

Lesser known.

In 1896, in what is one of the most unimaginable rulings in

the Court's history, the judges enacted Plessy vs. Ferguson.

This decision legitimized the incredulous segregation ordinances

and laws in racist southern states and made segregation legal

throughout America. The court defined "race" as

either black or white and instantly dissolved the entire Creole

population in southern cities. It wasn't until 1954, in Brown

vs. Board of Education, and in 1956 in Browder vs. Gayle that

the court eventually eliminated segregation in schools and

buses respectively.

In 1883, in Pace

vs. Alabama, the court ruled it illegal to have marriage between

races and this decision wasn't reversed until Loving vs.Virginia

which finally legalized miscegenation.

One of the most

laughable rulings was Bowers vs. Hardwick in 1986 which effectively

outlawed "abnormal" sexual activity in one's own

home! The rapid reversal came in Laurence vs. Texas which

finally ended the snickering in 2003.

In

its history the Supreme Court has enacted dozens of decisions

reversing earlier court actions on the amendments which changed

the original thinking of the framers. And yet presently the

concept of ‘originalism’ is being lauded as some

sort of sacred cow and the court’s history of change is

being ignored.

The

most recent and most controversial Supreme Court ‘originalist’

thinking comes from justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas

who both dissented in the Laurence vs. Texas fiasco. They have

expostulated on their decisions with statements exemplifying

their irrational philosophies:

Antonin

Scalia

"[There's] the argument of flexibility and it goes something

like this: The Constitution is over 200 years old and societies

change. It has to change with society, like a living organism,

or it will become brittle and break. But you would have to be

an idiot to believe that; the Constitution is not a living organism;

it is a legal document. It says something and doesn't say other

things . . . "

Scalia

believed that legal documents occupy the very top rung of reality

transcending epistemology, biological evolution, gender evolution,

evolving and hard fought racial and social norms, emerging mathematical,

physical, and chemical discoveries and laws, and the aforementioned

legal transformations of the last 2500 years. In sum, Scalia

placed the words of the framers of 200 years ago beyond the

scope of any reasonable thinking. He insisted that Supreme Court

decisions were to be made in an impenetrable vacuum of words

and syntaxes which could never be changed.

Later

Scalia mused that flexibility does in fact exist in the legislative

process. "You think the death penalty is a good idea? .

. . persuade your fellow citizens to adopt it. You want a right

to abortion? Persuade your fellow citizens and enact it. That's

flexibility." But with his history of judicial intransigence,

Scalia ignored the implications of his own statement. Whenever

‘flexed’ legislation came to his desk no matter

how sensible, he would decide against it based on his narrow

originalist thinking.

ClarenceThomas:

“Let me put it this way; there are really only two ways

to interpret the Constitution – try to discern as best

we can what the framers intended or make it up. No matter how

ingenious, imaginative or artfully put, unless interpretive

methodologies are tied to the original intent of the framers,

they have no more basis in the Constitution than the latest

football scores. To be sure, even the most conscientious effort

to adhere to the original intent of the framers of our Constitution

is flawed, as all methodologies and human institutions are;

but at least originalism has the advantage of being legitimate

and, I might add, impartial."

Thomas’s

assumption is that the correct tying of interpretations to ‘the

original intent’ can only be made by some static originalist

such as himself.

Much

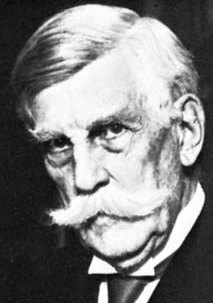

more enlightened rhetoric on the subject came from Oliver Wendell

Holmes in an opinion he rendered in the 1920 decision Missouri

vs. Holland:

Much

more enlightened rhetoric on the subject came from Oliver Wendell

Holmes in an opinion he rendered in the 1920 decision Missouri

vs. Holland:

"With

regard to that we may add that when we are dealing with words

that also are a constituent act, like the Constitution of the

United States, we must realize that they have called into life

a being the development of which could not have been foreseen

completely by the most gifted of its begetters. It was enough

for them to realize or to hope that they had created an organism;

it has taken a century and has cost their successors much sweat

and blood to prove that they created a nation. The case before

us must be considered in the light of our whole experience and

not merely in that of what was said a hundred years ago."

Woodrow

Wilson offered the following:

"Society

is a living organism and must obey the laws of life, not of

mechanics; it must develop. All that progressives ask or desire

is permission -- in an era when "development," "evolution,"

is the scientific word -- to interpret the Constitution according

to the Darwinian principle; all they ask is recognition of the

fact that a nation is a living thing and not a machine."

Donald

Trump’s nomination of Neil Gorsuch to the court was made

solely on the basis of his ties to Scalia’s ‘originalist’

thinking. Certainly Trump has never exhibited even the slightest

awareness of the court’s historical fluctuation and its

retracing of flawed rulings. Interestingly, Gorsuch’s

vetting has revealed evidence of demonstrated judicial expertise

beyond any pattern of originalism and Trump’s nomination

of him may actually prove to have ironical consequences.