Christopher

Labos is a Montreal doctor (Division of Epidemiology, Biostatistics

and Occupational Health McGill University )who writes about

medicine and health issues.

Mosquitoes

are the most lethal creatures on the planet. They kill millions

of people every year by spreading diseases like dengue, yellow

fever and malaria. Now mosquitoes (specifically the Aedes

aegyptii mosquito) are spreading the Zika virus, which

the World Health Organization says will infect three to four

million people by the end of this year. Mosquitoes are not a

summertime annoyance; they are a major public health problem.

Kill mosquitoes, and you save lives.

You

can use larvicides to kill them before they grow up into blood-sucking

adults, but the mosquitoes develop resistance after a while.

You can use the mosquitofish, Gambusia afiniis, which

will happily devour any mosquito larvae it finds. Problem is

they will devour everything else, too, and can become invasive

pests wherever they are introduced. Or you can fight fire with

fire and get mosquitoes to kill mosquitoes.

You

can use larvicides to kill them before they grow up into blood-sucking

adults, but the mosquitoes develop resistance after a while.

You can use the mosquitofish, Gambusia afiniis, which

will happily devour any mosquito larvae it finds. Problem is

they will devour everything else, too, and can become invasive

pests wherever they are introduced. Or you can fight fire with

fire and get mosquitoes to kill mosquitoes.

Oxitech,

a British biotech company, has developed a genetically modified

mosquito; the second genetically modified animal to come into

being (the first being the genetically modified salmon last

year). The United States Food and Drug Administration has approved

the genetically modified Aedes aegypti for a field

test in the Florida Keys, where the Zika virus has spread into

the U.S.

The

mosquito works like this. Researchers inserted a gene into the

mosquito’s DNA that produces a protein called tetracycline

transcriptional activator variant (tTAV). The tTAV blocks DNA

transcription so that cells can’t function properly. The

mosquito dies because of a fatal flaw in its DNA.

When

these mosquitoes are released into the wild, they breed with

native mosquitoes and produce genetically flawed offspring that

don’t survive to maturity. Therefore, no new generation

and no new mosquitoes. No mosquitoes means no spread of Zika.

There

is concern that these genetically modified mosquitoes will bite

humans and transfer dangerous genes to people. This would make

a great movie plot, but it can’t happen in real life.

When

mosquitoes bite you, they can transfer bacteria or viruses into

your blood stream. That’s how you get diseases like malaria,

dengue or chikungunya. But mosquitoes don’t transfer DNA.

The issue has been studied in both humans and animals, and mosquito

bites are not a vector for DNA transfer.

Think

about it: You’ve been bitten hundreds if not thousands

of times by mosquitoes, and yet you have no mosquito DNA in

you. Nor do mosquitoes have any human DNA. If DNA were transferrable

via mosquito bites, you would think some would have made its

way into our genome over the millennia mosquitoes have been

feasting on our blood.

However,

the point is moot because the mosquitoes modified by Oxitech

don’t bite humans. Only female mosquitoes bite humans,

and these genetically modified mosquitoes are all males. Problem

solved.

There

is always the concern that these genetically modified mosquitoes

will have some unforeseen effects on the environment. But they

have been studied and compared to the unmodified mosquito and

found be identical in terms of number of eggs laid, the egg-hatching

rate, larval survivorship and many other parameters. They won’t

spread across the planet (the mosquito does poorly in temperatures

under 15°C, which is why Zika likely won’t affect

Canadians unless they travel to warmer climates).

Also,

these mosquitoes are not some new invention. They were developed

in 2002 to fight dengue fever, but have now been repurposed

because of the Zika outbreak. They have been subject to field

trials in Brazil, the Cayman Islands and Panama and studied

for more than a decade.

But

most importantly, these are not super mosquitoes. They are regular

mosquitoes with a programmed genetic defect. Their only goal

is to mate with the native female mosquitoes to produce genetically

flawed offspring that won’t survive long enough spread

Zika to pregnant women.

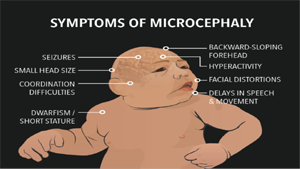

To

date, Zika has caused more than 1,800 confirmed birth defects

(with another 3,000 suspected). That number — not genetically

modified mosquitoes — should make us scared.