Nick

Catalano is a TV writer/producer and Professor of Literature

and Music at Pace University. He reviews books and music for

several journals and is the author of Clifford

Brown: The Life and Art of the Legendary Jazz Trumpeter,

New York

Nights: Performing, Producing and Writing in Gotham

and A

New Yorker at Sea. His latest book, Tales

of a Hamptons Sailor, is now available. For Nick's

reviews, visit his website: www.nickcatalano.net

A demagogue

is “a political leader who tries to get support by making

false claims and promises and using arguments based on emotion

rather than reason” (Merriam-Webster). Most people understand

this notion but few have knowledge of the irony involved in

its origin during a period of near miraculous political idealism

– the onset of Democracy in ancient Greece.

After

decades of political experiments in the sixth century B.C. during

which leaders (Solon, Pisistratus) grappled with the challenge

of giving justice to all citizens regardless of their economic

or social status, a revolutionary system was enacted by Cleisthenes

in 504 B.C. An assembly (ekklesia) was created in Athens

comprised of all citizens rich or poor where all could speak

on issues and vote for or against. No favoritism was given to

the wealthier or more powerful; a jury of peers would decide

the fate of a defendant during trials where arguments from all

Athenian citizens could be delivered and heard.

New

democratic assembly sessions opened with the presiding officer

asking “Who wishes to speak?” As the Athenian citizenry

(about 6000) all participated in the often vigorous debates

and discussions on the Pnyx hill under their magnificent acropolis,

it soon became obvious that those who could speak with the most

persuasive voices had the greatest say over the voters and voting.

Quickly, citizens rushed all over town seeking out teachers

who could help them orate more effectively and persuasively.

It was at that point that the art of ‘rhetoric’

came into being.

Teachers

or sophists as they became known flocked to the Agora or marketplace

in the center of Athens and held court. Those who gave the best

lessons and got the highest results made the most money. And

there is evidence that sophistry became the most coveted occupation

in the city with the most revered sophists garnering huge prestige

and influence.

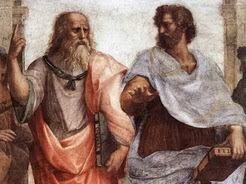

Who

were the principal creators of rhetoric? Many have heard of

Protagoras, Gorgias, Socrates and Demosthenes but few know about

Coras and Tisias -- Sicilian Greeks who most scholars credit

with starting matters off about 467 B.C. What was the substance

of their teaching? What techniques of speaking marked the success

of an influential orator?

Who

were the principal creators of rhetoric? Many have heard of

Protagoras, Gorgias, Socrates and Demosthenes but few know about

Coras and Tisias -- Sicilian Greeks who most scholars credit

with starting matters off about 467 B.C. What was the substance

of their teaching? What techniques of speaking marked the success

of an influential orator?

A huge

list of rhetorical terms has come down to us from antiquity.

There are hundreds of judiciously labeled and defined terms

and techniques that the sophists taught and it will serve us

to deal with only a few in order to understand the scope of

the achievements of these Athenian instructors. Credit must

also be given to the Romans who emulated the Greeks and translated

their terms into Latin expressions which are more familiar to

us.

Following

are brief examples of some techniques. For more detailed analysis

readers can consult any number of works on Rhetoric.

Syllogisms

were bedrock structures employed in mathematical and philosophical

reasoning: a) Bob is a person b) all persons are mortal c) therefore

Bob is mortal. But soon rhetoricians developed Enthymemes

which sounded like syllogisms but were based on opinion and

not logic: a) These clothes are tacky b) I am wearing these

clothes c) Therefore, I am unfashionable. Similar tricky techniques

include: Hypophora: wherein a speaker asks the audience

a question and then answers it himself i.e. “When he reminded

you of your old friendship, were you moved? No, you killed him

nevertheless.” Apophasis: wherein the speaker

brings up a subject by denying that it should be brought up:

“I forgive you your jealousy, so I won’t even mention

what a betrayal it was.” Zeugma (also called

Syllepsis): wherein a speaker uses a single word with

two other parts of a sentence but is understood differently

in each part: “Eggs and oaths are soon broken.”

There

were literally hundreds of these techniques developed by the

Sophists and utilized in political speeches. Some of the more

powerful ones were later re-labeled by the Romans and it is

these terms that moderns are more familiar with. Non Sequitur:

a statement bearing no relationship to the previous context

i.e. “He went to the same college as Bill Gates. He should

be famous too.” Argumentum Ad Populum: the appeal

to the popularity of a claim as a reason for accepting it i.e.

“the fact that the many citizens support the death penalty

proves that it is morally right.” Post hoc ergo propter

hoc: wherein the speaker claims that something causes another

thing simply because it occurred before i.e. “the current

economy’s health is determined by the actions of previous

presidents.”

There

is much evidence that when rhetoric was initially instituted

the Greeks thought that the techniques would be always used

for establishing the truth of the issue in question and never

to service any distortion of it. But as anyone can imagine it

didn’t take a genius to figure out that rhetorical expertise

would eventually be employed maliciously.

When

Aristotle came along and analyzed what had been happening since

the inception of democracy in his Rhetoric written

in 350 B.C. he immediately took note of the onset of deviousness

that had been developing over the years since persuasive rhetoric

was first taught. He wrote “Revolutions in democracies

are generally caused by the intemperance of demagogues.”

He singled out one of the most insidious techniques –

what we now refer to as argumentum ad verecundiam –

an appeal to one’s prejudice, emotions or special interest

rather than to one’s reason i.e. “How can he be

a good neighbour? He wasn’t born here.”

Aristotle

later wrote “The orator persuades by means of his hearers,

when they are roused to emotion by his speech; for the judgments

we deliver are not the same when we are influenced by joy or

sorrow, love or hate.” The influential Roman statesman

Seneca continued the warning “Reason herself, to whom

the reins of power have been entrusted, remains mistress only

so long as she is kept apart from the passions.” The comments

of the Sicilian Greek Gorgias, however, are the most dramatic:

“The power of speech has the same effect on the disposition

of the soul as the disposition of drugs on the nature of bodies.”

Unfortunately,

ever since its invention, iniquitous rhetoric has damaged reasonable

debate and often instigated deep chasms of injustice throughout

human history.

We

need only reference the horrific effects caused by Adolf Hitler

when employing argumentum ad verecundiam. Essentially, he began

by bemoaning the terrible economic conditions in post W.W. I

arousing anger and frustration in crowds he addressed. And then,

using the aforementioned illogic, he insisted that since many

prosperous businesses were owned by Jews they were to blame

for the poor economic conditions in Germany. What followed was

the horror of the holocaust. The madness all began innocuously

enough with a speaker simply appealing to the anger of the crowd

with passionate rhetoric focused on emotions and carefully omitting

rational thought.

Recently,

the same illogic has been employed by Donald Trump in his rhetoric

against Muslims. Because of the violence caused by international

terrorists (he neglects to note that much violence is attributable

to criminals of all races and creeds) he demands that America

denounce all Muslim peoples and segregate those who already

enjoy peaceful citizenship.

In

similar speeches he has deprecated, Hispanics, members of the

LGBTQ community, a Mexican judge, Afro-Americans, Native-Americans,

and Jews utilizing the same demagogic rhetoric originating thousands

of years ago.

Thus

irony and tragedy have come to us from the ancients. They thought

they were merely teaching concerned citizens to speak persuasively.

Instead they unleashed rhetorical weaponry for which we still

do not have any antidote. Demagoguery and demagogues continue

to flourish everywhere. It takes informed and aware listeners

to detect these insidious appeals to passion and prejudice and

condemn these orators of barbarism.