After

the last tree has been cut down, after the last river has been

poisoned,

after the last fish has been caught, only then will you find

that money cannot be eaten.

Cree prophecy

Maya Weeks is in it for the oceans. She is currently

writing a book about the gendered violence of marine debris

as byproduct of global capitalism. She blogs at anaturalhistoryofcolours.tumblr.com

and tweets at @looseuterus.The

Myth of the Garbage Patch was originally published at The

New Inquiry.

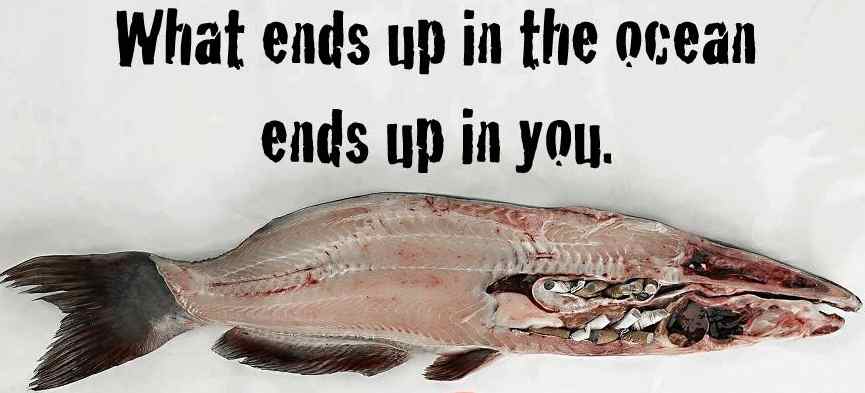

You

are probably already aware of the mass of garbage in the Pacific

Ocean, commonly known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch or

Trash Vortex or Trash Gyre or some combination thereof. You

are probably familiar with the description wherein this Garbage

Patch/Vortex/Gyre is represented as an island of trash roughly

twice the size of Texas floating somewhere in the vicinity of

Hawai’i. You may have heard that 80% of the waste comprising

the Garbage Patch is plastic and have probably seen images of

dead albatrosses --  dead,

you will have been told, because of the whole plastic bottle

caps and lighters it mistook for food -- or dead jellyfish or

seals or sea lions or sea turtles or whales. Somewhere in this

mesh of information lies the first myth of the Garbage Patch.

dead,

you will have been told, because of the whole plastic bottle

caps and lighters it mistook for food -- or dead jellyfish or

seals or sea lions or sea turtles or whales. Somewhere in this

mesh of information lies the first myth of the Garbage Patch.

Missing

from that myth is a key series of related facts. That the debris

breaks down into microscopic pieces. That the garbage actually

constitutes more of a ‘plastic soup’ than any kind

of patch or island, and that its pollutants are, as a result,

widely dispersed. That what breaks down doesn’t remain

solely in the Garbage Patch; that anywhere ocean currents converge

is this toxic soup. This soup is suffused with Bisphenol A,

pthalates, polychlorinated biphenyls, persistent organic pollutants,

and other remainders from discarded commodities that contribute

directly to the ocean acidification, killing fragile ecosystems

from the coral-based Great Barrier Reef off of Australia to

Inuit territories in the Arctic. Far from a solid, particulate

island, the Garbage Patch is, along with the rest of the ocean’s

water, in constant motion. And it doesn’t necessarily

stay at surface. In 2010 a team of ecologists, studying ocean

garbage patches, observed that the plastic in them accounted

for only a small portion of the plastic that has been produced

since World War II. “[W]e don’t know what this plastic

is doing,” said marine biologist Andres Cozar Cabañas,

who worked on the team, adding only that it “is somewhere

-- in the ocean life, in the depths.”

We

hear reports about the effects of this dispersed waste all the

time. Hundreds of thousands of marine birds, fish, reptiles

and mammals die annually from ingesting or becoming entangled

in marine debris. Sharks, hungry because their prey is dying

off, have been attacking humans more often in the last two decades

than ever previously. In Alaska, sperm whales are resorting

to snagging black cod from the lines of fishermen. Polymer fibers

get embedded on corals and on the ocean floor, where they suffocate

the coral communities that process carbon dioxide and release

pollutants into the food web. The number of anoxic zones --

places where oxygen levels have dipped too low to support life

-- keeps rising; the quarter of the planet’s biodiversity

whose home is the coral reef is rapidly decreasing; and a team

of ecologists have predicted the extinction of all saltwater

fish by 2048.

Yet

even at their most apocalyptic, these reports have the feel

of isolated incidents rather than the various manifestations

of a late capitalist global system in which value’s counterpart

is increasingly and necessarily waste. Under this system, the

overwhelming majority of goods that make convenient consumer

culture possible are composed of manmade polymers, including

but not limited to whiskey bottles, water and soda bottles,

bottle caps, six-pack loops, industrial felt, fishing rope,

nylon flags, fleece sweaters, shoes, purses, eating utensils,

cups, bowls, cell phones, computers, printers, furniture, toys,

and, of course, plastic bags.

We

weren’t always so surrounded with the stuff. Goods and

tools used to be made to last a lifetime out of organic materials

such as metal, wood and earthenware; when objects broke they

were repaired for as long as possible, then thrown to the earth

to decompose. Disposable income in the booming post-World War

II economy made it much easier for people used to living with

limited means to simply acquire new goods instead of continuing

to reuse old ones. According to Jeffrey Meikle, author of American

Plastic: A Cultural History, after World War II resin makers

“mounted a major educational effort to accommodate the

consumer to new, previously unknown plastics. People neither

naturally gravitated to the stuff, nor did they instinctively

throw it away, so the industry also had to insulate consumers

to plastic’s disposability.” It’s no coincidence

that the escalation of the abovementioned effects -- the rise

in hungry whales, shark attacks, dying coral, anoxic zones and

so on and so forth -- have coincided with quadrupled plastics

production since the massive neoliberal deregulation of the

1980s.

From

our vantage point within capitalism, it is difficult to identify

the origins of this plastic and see where it ends up in the

waste stream. It is difficult to trace a disposable container

of strawberries back to a multinational biotech corporation

and its compulsory distribution of genetically modified seeds

and pesticides to the resulting runoff that eventually washes

to the ocean. It can be a challenge to chart the paths of the

independently-contracted trucks that carry such containers to

the ships that export U.S. recyclables to Asia, never mind account

for where the waste goes upon landing. It’s hard to keep

in mind that the bunker oil fueling those ships and the processed

petroleum in that strawberry container might have been mined

by the same London-based oil company, and harder still to tease

out the many and various geopolitical infrastructures -- including

the surveillance cameras, barbed wire, and armed security checkpoints

of the global security state, for just one example -- that prop

up that company’s transnational holdings. It is easy to

treat the interdependence of these dynamics as too complex to

grasp. But to shy away from this complexity is to help maintain

the capitalist status quo.

While

we stay busy not seeing the complex market interplay that produces

and then abandons our plastics, the first myth of the Garbage

Patch continues apace. Liberal do-gooders advocate for the use

of massive nets to gather ocean plastic, imagining an easy extraction

of waste from environment. Meanwhile, back on land in the wealthiest

communities, people are urged to purchase solutions. Whole Foods

invites customers to eat in bulk from the salad bar with a bioplastic

fork derived from renewable sources, which, even if it manages

to break down in the oxygen-free environment of the sanitary

landfill, produces methane, a greenhouse gas twenty-three times

more potent than carbon dioxide, in the process. The startup

Shorecombers sells “Trash Blasting Tourism,” seven-day

trash cleanup vacations, half of which is spent online. Clothing

made from recycled plastics is available from brands like G

Star Raw and Patagonia, but these articles still shed microplastics

into the waste stream every time they are washed.

Green

capitalism is still capitalism, fundamentally unsustainable

and exploitative, and while the world’s most privileged

consumers insulate themselves, its devastating ecological effects

hit poor communities living in the world’s severest locations

especially hard. While Americans and Europeans with money can

fill their diets with certified ‘ethical’ fish,

this isn’t really an option for native people in the circumpolar

North -- including the Inuit of Greenland and Canada, the Aleuts,

Yup’ik, and Inupiat of Alaska, the Chukchi and other tribes

of Siberia, or the Saami of Scandinavia and western Russia --

whose cultures as well as diets depend on the ocean. Living,

working and fishing at the edge of glacial sheets, these people

can’t really choose not to eat fish with plastic embedded

in their scales, or the exorbitant concentrations of pollutants

in the larger marine mammals high up in the food web -- the

ringed seals, walruses, narwhals, and beluga whales -- that

are both dietary staples and sources of clothing and building

materials. Because of the cold and low Northern sunlight, pollutants

break down especially slowly – over the course of decades

or even centuries, according to Marla Cone, author of Silent

Snow: The Slow Poisoning of the Arctic. Cone has also noted

that even in the 80s Arctic mothers had seven times more PCBs

in their milk than their counterparts in Canadian cities.

Green

capitalism is still capitalism, fundamentally unsustainable

and exploitative, and while the world’s most privileged

consumers insulate themselves, its devastating ecological effects

hit poor communities living in the world’s severest locations

especially hard. While Americans and Europeans with money can

fill their diets with certified ‘ethical’ fish,

this isn’t really an option for native people in the circumpolar

North -- including the Inuit of Greenland and Canada, the Aleuts,

Yup’ik, and Inupiat of Alaska, the Chukchi and other tribes

of Siberia, or the Saami of Scandinavia and western Russia --

whose cultures as well as diets depend on the ocean. Living,

working and fishing at the edge of glacial sheets, these people

can’t really choose not to eat fish with plastic embedded

in their scales, or the exorbitant concentrations of pollutants

in the larger marine mammals high up in the food web -- the

ringed seals, walruses, narwhals, and beluga whales -- that

are both dietary staples and sources of clothing and building

materials. Because of the cold and low Northern sunlight, pollutants

break down especially slowly – over the course of decades

or even centuries, according to Marla Cone, author of Silent

Snow: The Slow Poisoning of the Arctic. Cone has also noted

that even in the 80s Arctic mothers had seven times more PCBs

in their milk than their counterparts in Canadian cities.

“At

the periphery of the global capitalist system,” writes

Chris Chen in “The Limit Point of Capitalist Inequality,”

“capital now renews ‘race’ by creating vast

superfluous . . . populations from the . . . descendants of

the enslaved and colonized.” It’s no accident that

plastic pollutants pool in the communities that capitalism has

historically treated -- and continues to treat -- as refuse.

Somewhere in that convergence -- in the attitude that everything

that gets thrown away stays far away -- lies the second myth

of the Garbage Patch.

“It’s

been the end of the world for somebody all along,” says

writer, spoken-word artist, and indigenous academic Leanne Simpson.

Recent studies show that marine pollution and ocean acidification,

once thought a separate if parallel disaster to climate change,

are in fact contributing to global climate disruption, suggesting

that, ecologically speaking, there is no such thing as somebody

else’s end of the world. Although the idea of the Garbage

Patch is entrenched in the collective imagination, we can use

language to help dislodge it. We can begin this process by rejecting

the myths of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. We must stop thinking

and talking in terms of an island that captures everything we

throw away in a faraway fever dream of plastic bags and marine

birds, and begin to map out the deeply interconnected web of

plants, animals, humans, and non-living things in which we actually

exist. We must recognize that capitalism depends on us not seeing

this web and that capitalism will never fix marine pollution

or climate change. As long as, like Andres Cozar Cabañas’

missing plastic, there are lives whose fates remain distant

and unaccounted for, everybody’s fates are at risk.