WHAT MAKES US HAPPY?

by

ROBB RUTLEDGE

_________________________________________________

Happiness is nothing more

than good health and a bad memory.

Albert Schweitzer

Our envy always lasts

longer than the happiness of those we envy.

Heraclitus

Robb

Rutledge is a Senior Research Associate at University College

London. The 'Great Brain Experiment' was named the best overall

game in the Wall Street Journal.

What

makes us happy? Well-being researchers have identified many variables

related to happiness, but we still don’t know exactly how

the events of our daily lives combine to influence how we feel

from moment to moment. People should get happier when good things

happen, but clearly this is not the whole story.

We designed

a study to investigate the relationship between rewards and happiness.

We brought people into the lab and asked them repeatedly about

their happiness as they chose between safe and risky monetary

options. Risky choices were gambles with equal probabilities (like

a coin toss) of a better or worse outcome. If they chose to gamble

on a given trial, they then found out whether they won or lost.

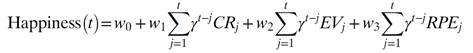

Based on the data, we developed a mathematical equation to predict

how self-reported happiness depends on past events. We found that

happiness depends not on how well things are going, but whether

things are going better or worse than expected.

Happiness depends on safe choices (certain rewards, CR), expectations

associated with risky choices (expected value, EV), and whether

the outcomes of risky choices were better or worse than expected.

This final variable is called a reward prediction error (RPE),

the difference between the experienced outcome and the expectation.

The neurotransmitter dopamine is thought to represent these signals

which might explain how people learn about rewards (if you get

more than you expected, next time you should expect more).

How do

our findings translate to real life? As soon as you make a plan

to meet a friend for dinner, your happiness should increase in

anticipation. If you manage to get a last-minute reservation at

a popular new restaurant, your happiness might increase even more.

If the meal is good, but not quite as good as expected, your happiness

should actually decrease. Our equation predicts exactly how much

happiness will go up and down, and our results reveal just how

important expectations are.

Happiness

is a difficult thing to measure, and one concern is that something

about being in the lab is important for our findings. Working

with a team of researchers at University College London, we developed

a smartphone app called the Great Brain Experiment. The app is

free and available in the Apple and Android app stores. We invite

everyone to download the app and to play the different games.

By playing the games, you contribute to ongoing research on important

questions in psychology and neuroscience. In the game ‘What

makes me happy?’ players choose between safe and risky options

to win as many points as they can.

Using

our mathematical equation, we could predict the happiness of over

18 000 people worldwide playing our game. Our results demonstrate

that something as complicated as happiness can be studied using

smartphones. As more people play the game, we can start to look

for differences between groups, like players of different ages

and cultures.

To better

understand the link between rewards and happiness, we also had

people play our game while having their brains scanned. We found

that neural activity in an area of the brain called the striatum

was closely related to reported happiness. When activity was high,

we could predict that happiness would increase. Because this area

has many connections to dopamine neurons, one interesting possibility

is that dopamine levels help determine happiness. Our equation

provides predictions that we can use to study the neural circuits

involved in happiness. We can ask questions like whether factors

that matter for happiness in young people differ in an important

way from happiness in adults. The equation also gives us a tool

for identifying differences between people that may help us better

understand mood disorders like major depression.

As a

researcher studying happiness, people often ask me how they can

be happier. Our equation might make it seem like low expectations

are the secret to happiness, but that’s not the case. Low

expectations do make it more likely that an outcome will exceed

expectations and positively impact happiness, but expectations

also affect happiness before we find out how a decision turned

out. We often don’t know the outcome of major life decisions

for a long time, whether taking a new job or getting married,

but our results suggest that positive expectations about those

decisions will increase happiness. In general, accurate expectations

may be best. Our expectations help us decide where to go for dinner

and tell us whether a new restaurant is as good as everyone says

it is. Although we all want to be happy, being happy all of the

time is probably not a good idea. If you were ecstatic after every

meal, you would never be able to decide which restaurant to go

to. Our happiness tells us whether things are going better or

worse than expected, and that may be a very useful signal for

helping us make decisions.

Low expectations

may not be the secret to happiness, but being able to predict

happiness based on past rewards and expectations bring us one

step closer to understanding happiness. By studying how happiness

depends on the interaction between our brains and our environment,

we hope to yield insights that contribute to the important goal

of improving human well-being.