|

|

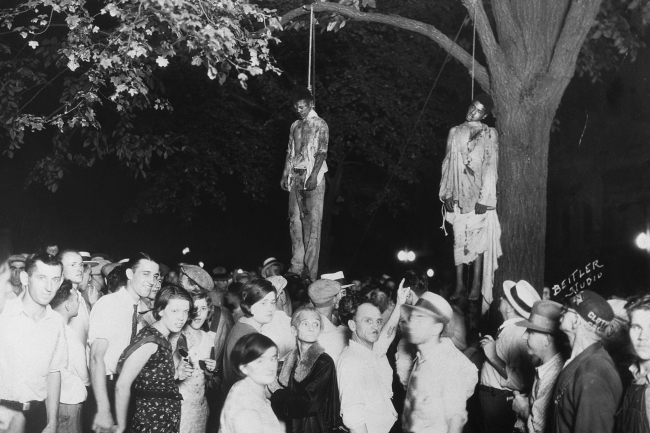

on a gnarled and naked tree

THE LITERATURE OF LYNCHING

by

HOLLIS ROBBINS

_______________________________________________________

Hollis Robbins is Director of the Center for Africana

Studies in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences and is Chair

of the Humanities Department at Peabody, where she teaches courses

on poetry, drama, film, and aesthetics. Her most recent article

is “Django Unchained: Repurposing Film Music,” Safundi,

16:3, July (2015). She is currently co-editing the Penguin

Portable Nineteenth Century Black Women Writers with Henry

Louis Gates, Jr., due out in 2017.

Ta-Nehisi

Coates’s book, Between the World and Me, a letter

to his son about race in America, takes its title from Richard

Wright’s brutal lynching poem, "Between the World

and Me" (1935). Coates offers the first three lines of

Wright’s poem as an epigraph:

And

one morning while in the woods I stumbled

suddenly upon the thing,

Stumbled upon it in a grassy clearing guarded by scaly

oaks and elms.

And the sooty details of the scene rose, thrusting

themselves between the world and me . . .

Wright’s

poem is one of the more fierce and forthright entries in the

canon of American poems about lynching. But I have never taught

it, though I have taught American and African-American poetry

in college courses for over a decade. It hasn’t been convenient.

The poem doesn’t appear in standard teaching anthologies

alongside the usual 20th-century works by Robert Frost, Langston

Hughes, and Elizabeth Bishop. Wright’s poem is curiously

absent from most anthologies of African-American literature

as well.

Are

the politics of anthologizing a matter of race, or the timidity

of introductory literary courses in the era of trigger warnings,

or both? How would adding Wright’s "Between the World

and Me" change the nature of the American poetry syllabus? Are

the politics of anthologizing a matter of race, or the timidity

of introductory literary courses in the era of trigger warnings,

or both? How would adding Wright’s "Between the World

and Me" change the nature of the American poetry syllabus?

Teaching

poems about lynching is complicated. On the one hand, a poem

on any subject is still a poem, a formal composition that registers

and distils something both particular and universal about human

existence. On the other hand, lynching is a uniquely American

political act that grounds the poem in horrific specificity

and resists a universal interpretation.

A "good"

lynching poem must capture and represent the horror of a specific

event. It must trigger strong feelings and perhaps rage. Moreover,

a good class discussion must address politics: not only the

politics of lynching but also the literary politics of creation

and publication. Who writes about lynching and when? Who publishes

the work and why?

In

short, the endeavour is not for the faint of heart.

Wright’s

"Between the World and Me" first appeared in the July-August

1935 issue of The Partisan Review, which announced itself as

no onger "an organ of the John Reed Club of New York"

but simply "a revolutionary literary magazine edited by

a group of young Communist writers, whose purpose will be to

print the best revolutionary literature and Marxist criticism

in this country and abroad." Richard Wright, the contributor

page states, "is a young Negro Communist poet of Chicago’s

South Side."

I have

often taught one of the earliest and most anthologized poems

about lynching written by an African-American poet: Paul Laurence

Dunbar’s mock-Romantic ballad "The Haunted Oak."

First published in The Century Magazine in 1900, the

poem tells the story of a lynching from the perspective of the

tree:

I

feel the rope against my bark,

And the weight of him in my grain,

I feel in the throe of his final woe

The touch of my own last pain.

And

never more shall leaves come forth

On the bough that bears the ban;

I am burned with dread, I am dried and dead,

From the curse of a guiltless man.

Dunbar

heard the tale about a haunted tree from a groundskeeper at

Howard University, an old man who had once been enslaved. I

mention to students that the Century’s editor

published the poem during an epidemic of lynching but cut two

stanzas about the haunting of the lynchers to soften the blow.

"The Haunted Oak" provokes lively conversation about

old-fashioned poetry, but in its antique diction and geographic

nonspecificity, it doesn’t provoke horror.

Claude

McKay’s sonnet "The Lynching," first published

in C.K. Ogden’s Cambridge Magazine (a British

journal) in 1920, provokes similar ambivalence:

His

spirit is smoke ascended to high heaven.

His father, by the cruellest way of pain,

Had bidden him to his bosom once again;

The awful sin remained still unforgiven.

All night a bright and solitary star

(Perchance the one that ever guided him,

Yet gave him up at last to Fate’s wild whim)

Hung pitifully o’er the swinging char.

Day dawned, and soon the mixed crowds came to view

The ghastly body swaying in the sun:

The women thronged to look, but never a one

Showed sorrow in her eyes of steely blue;

And little lads, lynchers that were to be,

Danced round the dreadful thing in fiendish glee.

Students

balk at the "perchance" and the "o’er,"

and the poem ultimately fails to work as either a well-crafted

sonnet or a poem about an American lynching, partly because

it is removed from local politics. Even students with blue eyes

feel distant from it.

Langston Hughes’s "Christ in Alabama," however,

published on the front page of a radical college literary magazine,

Contempo, in 1931, always shocks:

Christ

is a Nigger,

Beaten and black —

Oh, bare your back.

Mary

is His Mother —

Mammy of the South,

Silence your mouth.

God’s

His father —

White Master above

Grant us your love.

Most

holy bastard

Of the bleeding mouth:

Nigger Christ

On the cross of the South.

Hughes’s

poem states bluntly what McKay and others hint at, that a lynching

is a crucifixion. Contempo was launched by five white

college students at the University of North Carolina, in Chapel

Hill, out of a dorm room. One of the journal’s goals was

"encouraging literary controversy." The editors had

asked Hughes for a poem in response to the Scottsboro incident

(in which nine African-American teenagers were accused of raping

two white women).

Class

discussion generally focuses on the inflammatory first line

and whether college students today could or would publish such

a work. Students are uncomfortable with "the N-word."

We don’t generally get to the subject of lynching specifically.

Here

is where I might insert Wright’s "Between the World

and Me" into the syllabus as a poem also first published

in a magazine edited by young people aiming for revolution.

The poem is the second feature in the issue. It proclaims the

specific horrors of a lynching in painstaking detail. Here is

the last stanza:

And

then they had me, stripped me, battering my teeth

into my throat till I swallowed my own blood.

My voice was drowned in the roar of their voices,

and my black wet body slipped and rolled in their hands

as they bound me to the sapling.

And my skin clung to the bubbling hot tar,

falling from me in limp patches.

And the down and quills of the white feathers sank

into my raw flesh, and I moaned in my agony.

Then my blood was cooled mercifully,

cooled by a baptism of gasoline.

And in a blaze of red I leaped to the sky

as pain rose like water, boiling my limbs.

Panting, begging I clutched childlike,

clutched to the hot sides of death.

Now I am dry bones and my face a stony skull staring

in yellow surprise at the sun . . .

I can

imagine the hush of the classroom as the student called on to

read aloud finishes. There is little that we would consider

poetry here: no rhyme, no alliteration, no meter. There are

only stumbling words and death. Diana Fuss, one of the few recent

scholars who offers a sustained exegesis of "Between the

World and Me," reads the poem as a "corpse poem,"

by which she means a poem "not about the dead but spoken

by the dead, lyric utterances not from beyond the grave but

from inside it." The final stanza is so shattering, Fuss

adds, because the reader inhabits and identifies with the lynched

body.

As

a corpse poem and a revolutionary work, "Between the World

and Me" also shatters a common assumption that poetry —

particularly the poetry of nature — should seek to console.

Relief is not offered in another rural American lynching poem

that I have never taught, Lucille Clifton’s "jasper

texas 1998," with a dedication "for j. byrd."

The

poem was first published in the Spring 1999 issue of Ploughshares,

written for 49-year-old James Byrd Jr., who was dismembered

as he was pulled behind a pickup truck. The poem opens on a

country road:

i

am a man’s head hunched in the road.

i was chosen to speak by the members

of my body. the arm as it pulled away

pointed toward me, the hand opened once

and was gone.

why

and why and why

should i call a white man brother?

who is the human in this place,

the thing that is dragged or the dragger?

what does my daughter say?

the

sun is a blister overhead.

if i were alive i could not bear it.

the townsfolk sing we shall overcome

while hope bleeds slowly from my mouth

into the dirt that covers us all.

i am done with this dust. i am done.

Clifton’s

poem won the Pushcart Prize and is rarely anthologized except

in collections of Pushcart Prize winners. What does it mean

for a lynching poem to win a literary prize? Is the prize a

kind of consolation, given by the (mostly white) editors of

little literary magazines made uncomfortable by the absence

of Clifton’s usual tone of forgiveness?

Martin

Luther King Jr. notably said that 11:00 Sunday morning is the

most segregated hour in the nation. The world of poetry is equally

divided. Racial segregation is not only a matter of students,

syllabus, and textbook but also of categories of poetry. The

Open Yale Course "Modern Poetry" includes only one

lecture out of 25 on an African-American poet: Langston Hughes.

(Other American poets featured include Frost, Hart Crane, Ezra

Pound, and Wallace Stevens.) Langdon Hammer, the chairman of

Yale’s English department, who teaches the course, discusses

the most widely anthologized Hughes poem about lynching, "Song

for a Dark Girl" (1927):

Way

Down South in Dixie

(Break the heart of me)

They hung my black young lover

To a cross roads tree.

Way

Down South in Dixie

(Bruised body high in air)

I asked the white Lord Jesus

What was the use of prayer.

Way

Down South in Dixie

(Break the heart of me)

Love is a naked shadow

On a gnarled and naked tree.

In

his online lecture, Hammer considers the second stanza of the

poem without talking about lynching at all:

the

parenthesis holds in it a kind of brutal image, something horrifying

that must be set off slightly. The body is bruised, it shows

the marks of beating, of suffering, in advance of murder. It’s

lifted high in air, not in honour or tribute. Rather, to be

lifted in this way is to lose all agency, to be made lifeless;

all of this presented as a kind of syntactic fragment in the

poem, not yet integrated into the poem, so to speak, or it may

not yet be integrated into consciousness.

In

other words, Hughes’s poem is presented not as lynching

poem but simply as a work of modernist literature. Perhaps Hammer

examines parentheses and syntactic fragments because Hughes

does not offer ashes or bone fragments to sift though. Hammer

is not interested in history: He does not mention that the poem

first appeared in a middlebrow literary journal, Saturday

Review of Literature, or that several notorious lynchings

occurred in the year of its publication. Outrage is not the

point.

Hammer’s

integration of Hughes into his syllabus is laudable. But one

of the most influential anthologies of modernist poetry, Modern

Verse in English, 1900-1950 (Macmillan, 1958), fails to

include any African-American poets at all (although it does

include Allen Tate’s 1953 "The Swimmers," a

coming-of-age story about a white boy who sees a lynched black

body). Helen Vendler’s recent book, The Ocean, the

Bird, and the Scholar: Essays on Poets and

Poetry (Harvard University Press, 2015), includes only

one African-American poet — again, Langston Hughes.

Left

unsaid in the Yale course is how the inclusion of a black poet

changes the category of modernism, especially when Hammer introduces

Hughes as "the only modernist poet who begins as a busboy."

The

power of Coates’s Between the World and Me, like

the poem for which it is named, resides in its ruthless recognition

of violence to the black body in America. But how does one bring

that recognition into a literature class as a matter of literature?

I would

emphatically not teach Wright’s "Between the World

and Me" as just another poem, as the 2014 Kaplan AP English

test prep book does when it prompts: "Read the following

poem carefully. Then, in a well-organized essay, analyze how

the speaker uses the varied imagery of the poem to reveal his

attitude toward what he has found and how it affects him, paying

particular attention to the shifting point of view of the narrator."

The prep book prints Wright’s poem in all its ghastly

specificity.

The

prep guide states that high scores will be given to writers

who recognize "Wright’s masterful use of strong imagery,"

who demonstrate "perceptive understanding of … the

movement of the poem," who show "sensitivity toward

the subtle movement of the narrator from a casual observer to

a highly empathetic witness," and who "respond to

the prompt accurately."

The

writer is not expected to write about lynching, or about how

Wright’s sylvan opening lines change the nature of nature

poetry, or how references to clearings and saplings and feathers

and design might evoke, say, the poetry of Frost.

A fully

integrated poetry course would read "Between the World

and Me" alongside Frost’s widely anthologized "The

Road Not Taken," because Wright’s poem reminds us

that everything depends on perspective and whose woods these

are that Wright stumbles in. One must always recall that a road

diverging in a yellow wood, "in leaves no step had trodden

black," might just lead to the remains of a lynching.

The

poem "jasper texas 1998" is reprinted with permission©Lucille

Clifton.

|

|

|