It’s

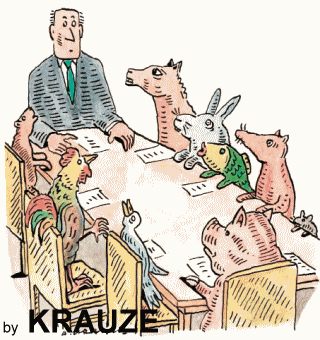

an old story, or another variation on the theme of elitism that

pits the righteous against everyone else. With visions of Jericho

and the soundtrack of The Lord’s trumpets in their higher

than holy heads, the great empathizers, or the compassionata

as they like to think of themselves, are comprised of individuals

and advocacy groups who vigorously argue the case for animal

sentience or sapience. Extrapolating data from the field work

of ethologists and neurological research, and then submitting

the hard-up facts to academic and scientific journals, they

are convinced that animals are thinking, feeling beings, and

that the rest of us – the fork and knife contingent --

are complicit in a daily animal holocaust for the sake of the

chicken and red meat we put on our plates for dinner and supper.

Cognitive

ethologist Mark Bekoff, from the University of Colorado, a

state where cannabis sativa just happens to be legal, wants

to declare a Universal Declaration on Animal Sentience. The

good professor and fellow animal rights activists contribute

to and support the  literature

contending, for example, that chickens are capable of empathy.

literature

contending, for example, that chickens are capable of empathy.

The proof

is indeed in the pudding. At the turn of the present century,

one of gallus domesticus's most noted members, having

successfully reduced the aggregate of species clucks to their

ontological essence, formulated the now celebrated “I

lay eggs, therefore I am.”

Doubters,

preferably before having dined on the dead, are invited to

examine the following published works and their telling titles:

“Five

Animals with a Moral Compass,” which

includes the lachrymose chapter “Dogs Feel Remorse.”

And an article that might make minimalists painters uncomfortable

in their thin skins, “Five

Animals Who Make Art.”

Professor

Bekoff, the author of Why Dogs Hump and Bees Get Depressed,

defines sentience as “the ability to feel, perceive,

or be conscious, or to experience subjectivity.”

From an article posted in livescience.com,

he goes on to explain: “Scientists know that individuals

from a wide variety of species experience emotions ranging

from joy and happiness to deep sadness, grief, and post-traumatic

stress disorder, along with empathy, jealousy and resentment.

There is no reason to embellish those experiences, because

science is showing how fascinating they are (for example,

mice, rats, and chickens display empathy) and countless other

"surprises" are rapidly emerging.”

The animal

sentience movement-manifesto is a cause that is attracting

more and more adherents, confident that it is occupying the

moral high ground. Where actions speak louder than words,

moral integrity is measured by what goes in and stays out

of your digestive tract. Overheard at an all-the-meat-you-can

eat breakfast buffet, and to the chagrin of the Toothpick

Manufacturers Guild: “I’d like to replace my order

of beef stroganoff with a plate of eucalyptus leaf and a side

order of freshly cut prairie grass sautéed in purified

air.” This and similar declarations have become the

rallying cry of the burgeoning movement.

Concerning

the immoral majority for whom animals are either a source

of pet pride or protein, the argument most commonly put forward

is “well, since you’re not one of them, how do

you know that animals can’t think, or get depressed

or feel jealousy or empathy? Just because they don’t

write novels or compose opera doesn’t mean they’re

not intelligent.”

It’s

the kind of argument that stops many of us in our human tracks

since we cannot scientifically demonstrate that animals aren’t

intelligent, just as agnostics can’t be 100% certain

there is no God.

But if we

offer thought to our evolution from birth through the transition

to adulthood, we will discover that animals cannot think,

are not sentient, capable of empathy, are not self-conscious,

because we ourselves were once 100%, unadulterated animal.

We merely have to revisit and deconstruct ourselves as we

were at the age of six months to ascertain the above contention,

and by extension, that animals are 100% dumb, and rightfully

without any rights. "The lamb licks the hand just raised

to shed its blood," writes Pope in An Essay on Man.

I propose

that apart from his potential, there is absolutely no difference

between the six month old child, let’s call him Little

Billie, than any other animal, one of whom we’ll name

Bessie the cow. At six months, the only difference between

Little Billie and Bessie is that the former’s genetic

code will allow him to evolve into a sentient, sapient, self-conscious

human being (William).

We need

not demonstrate what they have in common, which is everything.

Instead, our challenge is to make explicit their commonality,

which will correspond to what are commonly (universally) regarded

as either animal traits or animal behaviour.

We begin

with language. At six months old Little Billie has no vocabulary.

Like Bessie the cow, in respect to his basic needs and well-being,

he makes sounds. When Little Billie is hungry he whines/cries,

while Bessie moos. When Little Billie is happy, he’ll

babble and perhaps slobber. Bessie will unquietly release

flatus (methane) into the atmosphere.

Little Billie

doesn’t know he exists, doesn’t know that he is

alive, or what it means to die. Hold up a gun to Bessie’s

or Little Billie’s head and they won’t respond.

Little Billie and Bessie exist solely in the present; when

they recover from their hurts or come down from their highs,

they have no recollection of ever being hurt or happy. For

both Billie and Bessie there is no such thing as time (a yesterday,

a now, or future). Yes, they are categorically temporal, but

they do not exist in existential time.

In respect

to bodily functions, urination, excretion, they do it wherever

and whenever nature calls: there is no self-consciousness,

there is no observing critical public, there is no proper

place or evacuatory etiquette to follow.

We know

all the above to be true because when we, in good faith and

in pursuit of objective truth, reflect on our selves as we

were at the age of six months, we realize that we were exactly

like Little Billie and Bessie the cow. At six months old I

didn’t know I existed, much less was capable of empathy.

With all

due respect to Jonathan Swift’s mouth watering “Modest

Proposal,” what spares Little Billie, who is pure animal,

from becoming an intricate link in the food chain, is that

he has the potential to become a human being, while the animal

does not. When we speak of the severely retarded we are isolating

a gene malfunction that does not permit Little Billie to become

human. The severely retarded cannot speak. Present them with

a bag of money or a naked photo of Miss Universe and they

do not respond, just as they perform their bodily functions

without a nano-trace of self-consciousness. While they are

morphologically human, they are psychologically animal. And

if we decide to keep them around it is because we love them

like we love our pets.

Observing

Little Billie through an ontological lens, we find no behavioural

evidence that he is human. Which means – and of course

to the upset of loving parents everywhere -- all the Little

Billie’s we hold in our arms are animal and not (yet)

human. At the risk of being taxonomically incorrect, I propose

that only when Little Billie (as William) becomes self-conscious

does he merit the classification of human being.

The philosophy

of Martin Heidegger persuasively argues that we are born not

once, but twice: first as animal, and then again -- and only

very gradually until adolescence at which point the decisive

transition (metamorphosis) takes place and we become self-aware

-- as sentient/sapient human beings.

Heidegger

introduces the term Da-Sein to mark the appearance and standing

still of the now fully realized human being taking his first

breath as a being with a 'there,' which is the world. Little

Billie and Bessie are nowhere; they have no there. They simply

are, like trees are, like amoeba are.

Human beings

are uniquely privileged in that they can preside over and

reflect on the miracle of their becoming human, a miracle

that dwarfs the sum of all the metamorphoses in the plant

and animal world. When we ask of all that which human thought

is capable of offering thought to, surely this transition,

since we all undergo it, is most worthy of thought. Especially

if we become convinced the destiny of the planet is not unrelated

to making this extraordinary transition a priority of thinking.

“Only I can know for sure that what I am doing is a

way of not doing something else,” writes Canadian thinker

Mark Kingwell.

In order

to find our way out of a world “too much with us,”

brimming with diversions whose first effects are to steal

us away from ourselves, we look to metaphysics (the discipline

that designates “becoming” and “being”

as its first questions) to help make more explicit the transition

from the animal to the human. Biology and the sciences can

describe the event, but only philosophy can open up a realm

where the meaning of this transition can appear and be made

to stand still. That most of us, for our entire lives, leave

this transition ‘unexamined’ speaks to a value

system that is totally out of whack with the exigencies of

our time and the foreboding that throws the entire fate of

the planet into question.

However

discreet and incremental, the movement towards becoming self-conscious

is nothing less than growing out of our animal skins and becoming

human. To facilitate -- not the transition itself which is

biologically determined but -- the thinking that discloses

and articulates its existential significance, it is incumbent

that we grant the animal (the Little Billies that we once

were) his standing and category, at which point we will be

in a position to better grasp, in its full implication, our

humanity as it pertains to human conduct and the well-being

of the human habitat.

Sophocles

wrote “many are the wonders of the world, but none is

more wonderful than man.” Of all of man’s wonders,

surely none is more wonderful and worthy of thought than the

transition of Little Billie from animal to human being.

What favourable

or dire confluence of events will persuade us to make this

transition that which most deserves our undivided attention?

If we decide that our political systems have decisively failed

to identify those who are best fit to lead us to a better

place, what must happen in order to excite the necessity of

conceiving that better system? Is there a relationship between

being persistently uninterested in our miraculous transition

from the animal to the human (from Little Billie to William)

and our collective failure to raise to eminence the gifted

leaders in our midst?

In An Introduction

to Metaphysics, Martin Heidegger describes the creative

man who “sets forth into the un-said, who breaks into

the un-thought, compels the unhappened to happen and makes

the unseen appear."