Nick

Catalano is a TV writer/producer and Professor of Literature

and Music at Pace University. He reviews books and music for

several journals and is the author of Clifford

Brown: The Life and Art of the Legendary Jazz Trumpeter,

New York

Nights: Performing, Producing and Writing in Gotham

and A

New Yorker at Sea. His latest book, Tales

of a Hamptons Sailor, is now available. For Nick's

reviews, visit his website: www.nickcatalano.net

Even

a cursory analysis of output by Cuban musicians and composers

in the last half century or so yields strong evidence of noteworthy

achievement which, primarily because of political dispute, economic

embargo and cultural isolation, has been virtually ignored.

The musical spectrum involved is quite broad but a review of

Cuban distinction in jazz and affiliated musics goes a long

way in unearthing the significance of the Cuban musical tradition

and revivifying the prominence it deserves.

Composer

and multi-instrumentalist Mario Bauza (April 1911 -- July 1993)

trained as a classical musician (a characteristic of most Cuban

jazz virtuosi) and played clarinet in the Havana Philharmonic

at age nine. At 14 he recorded a Charanga in New York with legendary

classical composer/conductor Antonio Maria Romeu. In 1933, as

trumpeter/musical director for Chick Webb, he met and began

a long association with Dizzy Gillespie which resulted in “Cubop”

– the earliest form of Latin jazz. Their collaboration

continued through their years in Cab Calloway’s band and

would need multiple Ph.D dissertations to analyze its complexity

and revolutionary quality. Suffice it to say that Gillespie’s

(and Charlie Parker’s) bebop had apotheosized the American

music (work songs, blues, gospel minstrel) largely based on

West African traditions brought to the Americas but their jazz

was slavishly attached to the 4/4 and 2/4 time signatures of

European composers. When Gillespie worked with Bauza he realized

that the great polyrhythmic tradition of the West Africans (avoided

by puritanical North Americans) took hold in Latin America and

for modern jazz to take full advantage of this rhythmic richness

it had to incorporate the time signatures of Latin music.

It

is well known that when Bauza developed the 3-2/2-3 clave concept

and introduced Gillespie to Havana-born conguero Chano

Pozo whom Dizzy inserted into his big bebop band, Afro-Cuban

jazz became an instant hit (c.f. the Gillespie-Pozo collaboration

“Manteca”) and has steadily grown to become a staple

of modern music.

What

many fail to acknowledge is that despite Castro’s revolution

in 1958, the high standards of Cuban conservatories, the deeply-rooted

popularity of a variety of sophisticated local musics, and the

relentless prominence of musicianship in even the poorest families,

the development of Cuban prodigies has continued unabated.

Interestingly,

since Cuban socialism assumed political control in 1958, the

list of Cuban musical luminaries has grown apace, and, while

some have sought to leave the island, politics has not always

been the reason. It is clear that opportunities for success

have always been greater in New York than in Havana.

There

are so many Cuban giants – the names Machito, Mongo Santamaria,

Marco Rizo, Chucho Valdes, Xavier Cugat, Chico O’Farrill,

Candido Camero, Ruben Gonzalez, Carlos Valdez, Gonzalo Rubalcaba,

all emanate from Havana and came to America both before and

after the revolution. To summarize their accomplishments would

take more space than we have here.

In

my years as a jazz reviewer, I have often written about the

music of two of the great musician/composers who long ago emigrated

from Cuba; just last month I heralded a relative newcomer .

. . the parade continues.

When

Paquito D’Rivera arrived in New York in 1981, he became

an instant phenomenon. He wisely chose to display his prodigious

improvisational saxophone technique in his initial CDs, club

and concert performances and media stints. He quickly amassed

a mountain of Grammys (14 at this writing) gaining huge popularity

and musical celebrity. But there was still more to come.

When

Paquito D’Rivera arrived in New York in 1981, he became

an instant phenomenon. He wisely chose to display his prodigious

improvisational saxophone technique in his initial CDs, club

and concert performances and media stints. He quickly amassed

a mountain of Grammys (14 at this writing) gaining huge popularity

and musical celebrity. But there was still more to come.

Like

Mario Bauza, D’Rivera was a classical music prodigy performing

at age ten with the National Theater Orchestra, studying at

the Havana Conservatory, and becoming a featured soloist with

the Cuban National Symphony at age seventeen. In New York, jazz

writers hailed him as “the Latin Charlie Parker,”

nevertheless, he steadily began to widen his reputation by unveiling

his classical compositional gifts and writing ambitious extended

works. These days he can be seen playing inventive clarinet

passages with his Chamber Jazz Ensemble and winning classical

awards and collecting honorary doctorates. The full extent of

his genius will take scholars many years to measure.(c.f. my

essay “The New Paquito D’Rivera” 11-7-2010

www.allaboutjazz.com)

Another

Cuban titan whose reputation soared the minute he landed at

New York’s JFK airport is Arturo Sandoval.  Again,

it was his phenomenal jazz (trumpet) playing that secured instant

fame (10 Grammys). However, Sandoval also was a Cuban classicist

(studying at age twelve) who, since his meteoric rise, has performed

with symphony orchestras worldwide. He has also received an

Emmy award for composing the underscore of the HBO movie based

on his life For Love or Country starring Andy Garcia.

One of the most unforgettable performances in modern jazz history

is Arturo Sandoval Live at the Blue Note in 2012 (Video

available on YouTube). His multi-instrumental/vocal pyrotechnics

on this outing serve nicely as a metaphor for anyone interested

in learning about the breadth and depth of the Cuban music scene

at the millennium.

Again,

it was his phenomenal jazz (trumpet) playing that secured instant

fame (10 Grammys). However, Sandoval also was a Cuban classicist

(studying at age twelve) who, since his meteoric rise, has performed

with symphony orchestras worldwide. He has also received an

Emmy award for composing the underscore of the HBO movie based

on his life For Love or Country starring Andy Garcia.

One of the most unforgettable performances in modern jazz history

is Arturo Sandoval Live at the Blue Note in 2012 (Video

available on YouTube). His multi-instrumental/vocal pyrotechnics

on this outing serve nicely as a metaphor for anyone interested

in learning about the breadth and depth of the Cuban music scene

at the millennium.

The

Cuban virtuosi keep coming. Just a couple of months ago I reviewed

a concert given by Grammy nominated composer/pianist Elio Villafranca,

classically trained at the Instituto Superior de Arte in Havana.

This latest edition in the parade of Cuban musical cognoscenti

sits on the faculty of The Juilliard School and has recently

triumphed with a composition dubbed Cinqué: Suite

of the Caribbean – which captures the almost extinct

music of the African Congo.

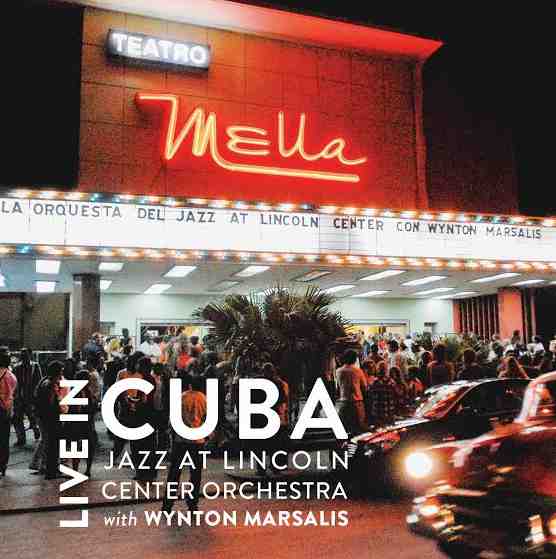

No

American agency has championed the cause of Cuban music more

than Jazz at Lincoln Center. Since its inception JALC has continually

included productions of Afro-Cuban sounds in its seasonal concert

series; and, in 2010, in anticipation of the recent Obama-led

transformation in Cuban-American relations, JALC artistic director

Wynton Marsalis brought the Center’s orchestra to Havana

for a historic concert and live recording. The resulting CD

on Blue Engine Records, Live In Cuba (available August

21), “is a document of the two nations’ indelible

cultural connections, of a journey into uncharted musical territory,

and of some of the world’s most virtuosic musicians sharing

a stage.”

Recorded

in front of huge sold-out crowds over three nights at Havana’s

Mella Theatre, Live In Cuba includes the orchestra

playing Duke Ellington standards, classic Afro-Cuban selections,

and new compositions from the band members. On Disc 1 bassist

Carlos Henriquez composed and arranged a burner dubbed “1,

2/3’s Adventure” which recalls some of the Latin

shout bands of yore (some of which I played in i.e. Tito Rodriguez,

Tito Puente). A stunning piano solo from Don Nimmer highlights

the track along with Henriquez’ bass improvs and trumpeter

Marcus Printup delights with a solo reminiscent of the Latin

masters of old. A tribute to legendary Bolero composer Ernesto

Duarte is delivered featuring Bobby Carcasses singing Duarte’s

“Como Fue.” This tune was often referenced by Desi

Arnaz and his eminent arranger Marco Rizo on the old I Love

Lucy show.

Recorded

in front of huge sold-out crowds over three nights at Havana’s

Mella Theatre, Live In Cuba includes the orchestra

playing Duke Ellington standards, classic Afro-Cuban selections,

and new compositions from the band members. On Disc 1 bassist

Carlos Henriquez composed and arranged a burner dubbed “1,

2/3’s Adventure” which recalls some of the Latin

shout bands of yore (some of which I played in i.e. Tito Rodriguez,

Tito Puente). A stunning piano solo from Don Nimmer highlights

the track along with Henriquez’ bass improvs and trumpeter

Marcus Printup delights with a solo reminiscent of the Latin

masters of old. A tribute to legendary Bolero composer Ernesto

Duarte is delivered featuring Bobby Carcasses singing Duarte’s

“Como Fue.” This tune was often referenced by Desi

Arnaz and his eminent arranger Marco Rizo on the old I Love

Lucy show.

Disc

2 includes “Limbo Jazz,” a piece by Duke Ellington

arranged by tenor saxist/clarinetist Victor Goines. Ellington

addressed his interest in latin/Calypso music with this creation

based on the chord changes to “Happy Birthday.”

Delightful soloing from trumpeter Ryan Kisor and baritone saxist

Joe Temperley highlight the tune. On Dizzy Gillespie’s

“Things To Come” -- a rapid-fire standard arranged

by Gil Fuller -- we hear Wynton Marsalis soloing with up tempo

articulation reminiscent of his early days with Art Blakey.

The

Cuban audience reception to the band’s stellar performance

adds an element of nostalgia to the recording and presages a

new era in Cuban-American musicalizing. The recording should

help pave the way for new scholarship about the Cuban masters

of yore and introduce young listeners to the often overlooked

musical heritage of this contentious island in the Caribbean.