Inthe portraits,

the slippery backgrounds echo the depthless grey matter

of space. The astrophysicist, to better grasp the notion

of the boundless, extends an imperfect numerical function

to infinity while the painter drains the colour out of his

pigment for the same effect. Each is asking how brief is

a human life that is bound on all sides by the infinite.

To draw attention

to the largest questions posed by existence, the Swiss artist

Alberto Giacometti (1901-66) decided  that

the portrait would be the optimal place for his inquiry

to take shape and find its proper expression. And even though

in his life time he would come to be regarded by his peers

as a portrait master, he always insisted (in his interviews)

that the moment the sitter took his place he became a mystery.

that

the portrait would be the optimal place for his inquiry

to take shape and find its proper expression. And even though

in his life time he would come to be regarded by his peers

as a portrait master, he always insisted (in his interviews)

that the moment the sitter took his place he became a mystery.

Giacometti’s

special relationship with his amorphous muse (his brother

Diego) was a constant source of angst and exultation, one

which he refused to terminate or resolve to his satisfaction.

His combined obsession and determination – pace Sisyphus

-- to confront the ineffable on its own terms has resulted

in some of the most compelling portraiture in the history

of painting. Both Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir

were fascinated by their painter friend, who was never satisfied

with his work and claimed he was a better writer than painter.

As much as any

artist in the 20th century Giacometti is its designated metaphysician,

in large part because he is not interested in the flesh qua

flesh but in the manner in which the bone structure and skeleton

relate to and anchor the spirit, and call into question the

mostly inscrutable, fugitive aspects of existence.

Why the line,

his gallery of portraits asks, and not the infinite possibilities

inherent in colour?

A line can mark

off what is inside or outside, as in a territory. It is

where inclusion and exclusion meet, and existence  and

non-existence are meshed together and reflected back. Giacometti’s

line, which is a profusion of lines, is less interested

in capturing the likeness of the person than the essence

he embodies, which accounts for the haunting, disembodied

feel to his portraits.

and

non-existence are meshed together and reflected back. Giacometti’s

line, which is a profusion of lines, is less interested

in capturing the likeness of the person than the essence

he embodies, which accounts for the haunting, disembodied

feel to his portraits.

The line, unlike

a volume of colour, invites us to look past or beyond it,

into the dark matter of infinity, into the nothingness that

shadows and animates the subject. Every time the sitter

sits he is confessing that his temporality is not a choice

but a destiny that cannot be double crossed. Where Giacometti’s

restless, nervy lines meet and conflict, man’s essential

humanity is laid bare, but we’re not sure if it is

consequent to the sitter’s momentary expression or

his ambiguous relationship to the infinite.

Giacometti’s

portraits continue the silence that begins with the “Mona

Lisa” and implodes into Edward Munch’s “The

Scream.” It's the silence of wind blowing through

a hollowed out rib cage, of driftwood that is no longer

a tree but whose treeness is indestructible.

Year after year,

it is the same sitter, his brother Diego, whom the artist

claims he doesn’t recognize. By entering this confession

into the public domain, Giacometti is not striking a pose

or bringing attention to his art through the cult of personality.

He is he proposing that in order to know anything at all it

has to be stripped of everything that is familiar at which

point it can be meaningfully encountered?

When the sitter

arrives he brings with him his fears and vanity, confessions

and conceits, and the body with which he negotiates the world,

all of which, under Giacometti’s incisive gaze, are

illusory, as short-lived as a lifetime dropped into the abyss

of eternity. Giacometti’s portraits singlehandedly open

up a realm in the history of art where the artist and his

materials convene in order to reveal man’s essential

fragility and apprehensiveness before the fact of his finitude.

And even though he is uniquely able to draw out and isolate

the metaphysical dimension of existence, paradoxically no

artist has captured appearances more emphatically, more robustly

-- and this holds true for his fleshless, mummy-like sculptures.

Just as Marcel

Proust's À la recherche du temps perdu illustrates

how every life can be rendered meaningful as the first effect

of intentionally reflecting on the past, Giacometti’s

oeuvre invites us to reflect on the possibility of meaningful

existence by rendering strange and foreboding that which

is most near -- the person sitting opposite us. Giacometti

makes it his essential task to strip the sitter of all his

daily entanglements, which conspire to protect him from

his manifest perishability, in order to not humiliate but

free him.

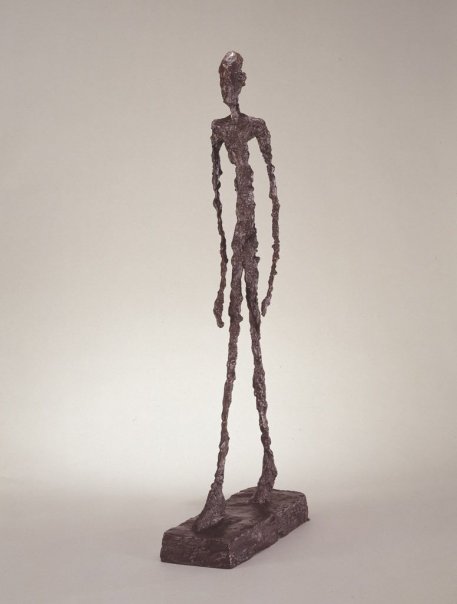

Since

Giacometti is also a sculptor who must work with solid materials

that withhold transparency and refuse disembodiment, how

is he to make bronze reveal the human condition? How can

tempered bulky matter be converted into a medium that speaks

to man’s existential predicament?

Since

Giacometti is also a sculptor who must work with solid materials

that withhold transparency and refuse disembodiment, how

is he to make bronze reveal the human condition? How can

tempered bulky matter be converted into a medium that speaks

to man’s existential predicament?

Giacometti ingeniously

solves the problem by creating quasi 2-dimensional figures,

many of them drastically reduced in scale. His roughly hewed,

match-stick like figures, such as “Walking Man,”

almost have no breadth, and the heads are shrunk as if the

artist doesn't quite recognize who is before him, while the

withering legs disappear into disproportionately large feet

firmly fixed (nailed) to the ground -- clinging to dubious

epistemological certainties? So delicate and insubstantial

are Giacometti’s sculptures, that like fledging birds

for the first time airborne, we want to take them in our hands

and reassure them that they are here and now and not alone.

By depriving

his bronze figures of their physical human dimension, he

discloses their (man’s) frailty and resolute humanity.

In their attenuated but dignified bearing, he both honours

and defends their terrifying silence as well as their majesty.

And as we stand before them, sometimes towering over them,

we may come to discover our own (diminished) sense of proportion

and the unexpected consolation an encounter with an artwork

can provide.

It requires

repeated acts of courage to make the human condition serve

as one’s lifelong muse, which is why Alberto Giacometti’s

portraits and sculpture rank among the 20th century’s

most significant art.