authenticity issues in

THE SEX TRADE

by

ZAHRA STARDUST

________________________________________

Zahra Stardust is a writer and sex worker. Her

essays can be found at www.zahrastardust.com

and zahra.org.au.

Said of Zahra: "Sexy beautiful bodies are an expensive

dime a dozen; what distinguishes this women is that she can

think and write."

WHAT

IS FAKE AND REAL IN THE SEX INDUSTRY

As

someone who works in the sex industry – in spaces that

purport to be real as well as spaces that are accused of as

being fake – it seems like there is no distinct line between

the two. As  someone

who works with a body that is sometimes perceived as real and

other times read as fake – it seems that the bodies which

move across these spaces are equally fluid.

someone

who works with a body that is sometimes perceived as real and

other times read as fake – it seems that the bodies which

move across these spaces are equally fluid.

As

someone whose pink bits have been airbrushed in magazines, but

which have also been on explicit display; who performs both

with and without make-up; whose real name is my stage name,

distinctions between fake and real don’t always make sense.

I experience

pleasure at work in the mainstream sex industry that I certainly

perceive as real. This pleasure comes from physical sensations

(lactic acid, endorphins, sweat, carpet burn, whipping hair,

a double ended dildo angled against my g-spot, real orgasms)

but also from the thrill of voyeurism (exhibitionism, cameras,

being naked in front of thousands of people).

Pleasure

comes from creative aesthetics (coordinating colours, angles,

props and shapes) and the kick of doing something that is (to

some) taboo. I consider that pleasure a genuine part of my own

sexuality. Sure, it’s work – and during shows I

am also thinking about choreography, musicality, crowd control,

not falling over, pole grip, camera angles, the audience member

who is wandering off with my g-string – but work and pleasure

are not mutually exclusive.

Yes,

it can be mundane, repetitive and sometimes I end up with pole

bruises, aching muscles and an intolerance for drunk men, but

I use the stage as a platform to explore my own desires, and

this assumption that what we do at work and the pleasure we

experience from it isn’t real must be problematized. My

vagina will tell you otherwise.

At

the same time, websites that purport to depict real or redefined

beauty, often seem to be just as conventionalized as the mainstream

genres they criticize. Alternative nude modeling site Suicide

Girls gives calculated instructions on their website about the

kinds of photos, make-up and aesthetic sets they accept: tasteful,

picture perfect shoots with ‘a little bit of face powder

and mascara and freshly dyed hair, but specifically not cheap

wig(s), top hats, stripper shoes, food or things that look cheesy,

gross or creepy.

Similarly,

the girl next door look of the Australian all-female explicit

adult site Abby

Winters represents an alternative to glamour

photography, featuring make-up-less, amateur adult models –

but models are still required to cover up hair re-growth, remove

piercings, and not have any scratches, marks or mosquito bites

for the shoot in order to appear healthy.

Other

sites I’ve shot for speak about the importance of models

representing their own sexuality, but then go on to qualify:

“We might get you to tone down the eye make up a bit,”

“Maybe don’t talk about politics,” “Lesbians

don’t really use double-enders do they?” One company

asked me repeatedly to stop wearing frills.

In

doing so, these sites produce bodies of a particular class,

size and appropriate femininity, which are marketed as real,

but which are equally constructed, conventionalized and cultivated.

This fear of replicating cheesy, predictable mainstream porn

means that depictions of real sexuality are often similarly

clichéd, albeit with a different set of aesthetics.

In

their avoidance of the mainstream (whatever that means), alternative

porn (whether it brands itself queer, feminist or erotica for

women) can sometimes replicate and reinforce what Gayle Rubin

calls “Good, Normal, Natural, Blessed Sexuality:”

the sex is vanilla and involves only bodies (without objects

or toys). Sex occurs in the home, between members of the same

generation and only within couples. The scenes are soft, gentle,

usually in natural light and every-day clothes (which in my

experience means we are expected to bring Bonds underwear).

To

think that this could be any more real than mainstream porn

seems strange to me, especially when it is produced in an environment

that is completely staged: our movements are restricted by camera

angles, someone is standing beside us operating the equipment,

many of us are professionals pretending to be amateur, and in

true documentary style, we are expected to cum on cue. These

kinds of websites are marketable and loveable because they refuse

to define themselves as porn – even though, as Annie Sprinkle

said in the Herstory of Porn, the difference between

erotica and porn “is all in the lighting!”

To

think that this could be any more real than mainstream porn

seems strange to me, especially when it is produced in an environment

that is completely staged: our movements are restricted by camera

angles, someone is standing beside us operating the equipment,

many of us are professionals pretending to be amateur, and in

true documentary style, we are expected to cum on cue. These

kinds of websites are marketable and loveable because they refuse

to define themselves as porn – even though, as Annie Sprinkle

said in the Herstory of Porn, the difference between

erotica and porn “is all in the lighting!”

It

is an important goal to make sexually explicit material that

does not prescribe unrealistic standards, perpetuate hegemonic

gender stereotypes or marginalize diverse sexualities. But many

of us in the sex industry will tell you that those stereotypes

and marginalization come – not from audiences or clients

– but from public reductive readings of our work and stringent

legal frameworks.

These

frameworks determine which bodies and sexual practices can legally

be portrayed and whose voices are heard or silenced. Callous

distinctions between fake and real present un-nuanced and uncritical

readings of the sex industry and contribute to regressive laws.

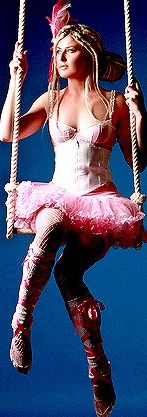

Sure,

we may play with, embody and embrace hyper-femininity, but we

are no less authentic, or political, or real, because our lip

gloss is hot pink instead of nude. We don’t need to tone-it-down

to be any more queer, radical or real. Our bodies may look unrealistic

to you, but the labour of preparing for work gives erotic performers

a sentient, working knowledge of gender performativity.

Much

of the time, our work is far from glamorous. I return from work

with smudged mascara, sticky lube, patchy fake tan, knotty hair,

smelling like sweat and vaginal fluid – and the customers

experience this up close and personal. My vagina certainly isn’t

airbrushed when I get it out at buck’s parties, complete

with shaving rash, discharge and blonde hair caught in my clit

ring.

Merely

working in this industry gives us access to hundreds of real

bodies – all different, all diverse, all unique. We all

bring real, orgasmic pleasure, to audiences, clients, and readers

(of many genders).

Blaming

certain kinds of femininity and reading our bodies as fake,

normative and indulgent is part of a wider culture that does

not value – and actively ridicules – femininity.

Reading our bodies as fake insults femmes. Many of us feel our

femme presentation is a way of queering femininity; glitter,

six-inch thigh-highs and suspender belts may be far more natural

for many queer femmes than bare feet and beige make-up.

To

call us fake valorizes masculinity above femininity, privileging

masculine or androgynous embodiment (an absence of make-up,

hair-removal and accessories) as real and represents femmes

as superficial and trite dupes who cannot be considered serious

feminist or queer subjects.

The

irony is that you can never win – appropriate femininity

is unachievable. We are either too much or not enough. Our hyper-femininity

is often so far beyond normative feminine ideals that it brings

us social censure – our make-up is too thick, our heels

are too high, our breasts are too large. As Rosalind Gill writes

about women in media, our “bodies are evaluated, scrutinized

and dissected” and are “always at risk of “failing.”

Dyke

porn in particular uses authenticity to market products. Girls

site HotMoviesForHer.com asks in their advertisements, “Sick

of gay-for-pay straight girl sex? So are we” and instead

offers “Real lesbian porn.” This is an important

response to the imitation of homosexual desire by the heterosexual

majority for financial reward, and a reaction to discrimination

and underrepresentation of lesbian sexuality. Further, it raises

important issues about representation, inclusion, accessibility,

and which bodies and sexualities are depicted as erotic or desirable.

However,

these critiques also assume that for adult performers, there

are clear distinctions between what is authentic and performative,

or solid lines between gay and straight, whereas often the protagonists

of girl-girl porn/striptease/sex work – straight and queer

–may experience a blending of both.

Australian

Porn Star Angela White’s research shows that even where

straight-identifying women perform in girl-girl, femme-on-femme

pornography aimed at straight male audiences, the process of

selling sex can queer their heterosexuality. In her interviews

she found that the straight women found themselves enjoying

lesbian experiences in a way that confused their heterosexual

identity, made sexual identity categories redundant and “transform(ED)

their own sexual identity.”

There

is some amazing queer and feminist porn around that is diverse

and celebratory. But I’m not convinced that distinctions

between fake and real are all that useful, or necessary. To

call somebody fake involves a whole set of assumptions about

their body, identity, gender, sexuality and politics, about

what is natural, normal, which sex acts are real, what is authentic

for whom, and how one must look and behave to be feminist or

queer.

It

puts limits on the kinds of sexual encounters and relationships

that are real, discounting the intimate experiences we have

with clients every day. Using the fake/real distinction to denigrate

certain sexualities, shame femininity and blame the sex industry

for gender oppression is too easy. It perpetuates a language

that is whorephobic, femmephobic and slut shaming, which is

being co-opted and reproduced as acceptable in mainstream media,

academia and popular culture, but also (dangerously) by feminists,

queers, and fellow smut-makers.

As

a queer femme sex worker, reading our bodies and sexualities

as fake is offensive to me and my community. Is it acceptable

to you?