While in Mexico

during the Christmas holidays, in the seaside village

of Barra de Navidad, I rented a $35/night hotel room that

included a small kitchen and living room, AC and cable

TV. Forgoing sun and sea during the holy  Navidad weekend, I watched no fewer

than 20 gloriously gory, one-sided altercations between

bull and matador, and was now in the mood for the real

thing.

Navidad weekend, I watched no fewer

than 20 gloriously gory, one-sided altercations between

bull and matador, and was now in the mood for the real

thing.

When a local

policeman explained that in Cihuatlán, the nearest

town with a Plaza de Toros, they don’t kill the

bull, I couldn’t help but register huge disappointment.

In point of fact my blood began to boil: the nerve,

the outrageous pretense of sparing bull in a country

that fessed up to 43,000

homicides in 2023.

My interlocutor,

no doubt, was equally disappointed, there being no basis

for extracting a ‘tip’ from our brief question

and answer summit. But it was a sleepy day in this tranquil

coastal town of 5,000, so, on my behalf, he phoned Cihuatlán

and assured me that there would indeed be ‘no

blood’ on Sunday, when festivities would begin

at 5 pm.

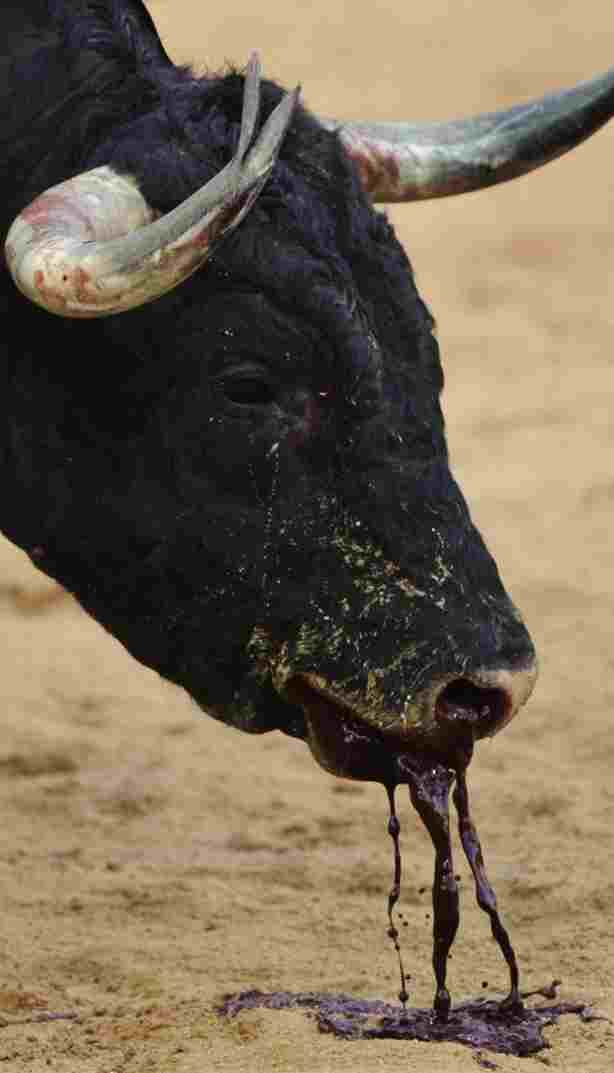

For all

the laudatory, madly inspired tomes written on the high

art of bullfighting, consider the fact that the average

bull is worth 35 litres of blood. If it dies a deliciously

slow death at the hands of an incompetent torero (matador),

it will leak about 10 litres of that. Which means on

a good day the spectator will be treated to 100 litres

of spilled blood, which, in theory, should be enough

to get the afición from Sunday to Sunday without

having to seek out alternative sources. When I aver

that I was in the mood for blood, I wanted to see --

and without apology -- a veritable blood bath, the earth

turn rojo and watch bulls die a slow death.

Nota

Bene: In the spirit of finding common ground with

those for whom the sport is an outright abhorrence,

the bull enjoys a verifiable after-life in the restaurant

menu circuit.

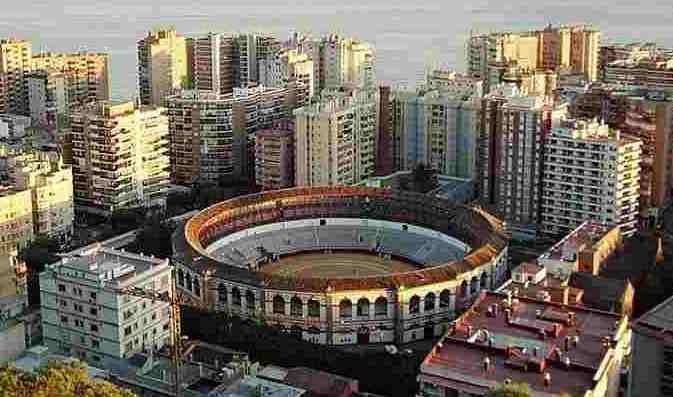

To finger-quick

readers who have already crossed me off their lists

and assigned me to the category of unregenerate, blood-thirsty savage, I propose that

my lust for blood is not an isolated perversion. Where

good society hasn’t banned the sport, the bull

rings are full to capacity. -- and the red dye used

in T-shirt manufacture is certified organic.

blood-thirsty savage, I propose that

my lust for blood is not an isolated perversion. Where

good society hasn’t banned the sport, the bull

rings are full to capacity. -- and the red dye used

in T-shirt manufacture is certified organic.

Is it beyond

the pale to suggest that human beings are most likely

to rise to the occasion of authenticity when gathered

as a punitive mob or assembled to witness a blood-letting?

What draws

(after Holy Communion) the empirically vampiric to the

bull ring is the same that makes a heavyweight championship

fight the most watched event on the planet, that brings

many to near delirium during a Formula I crash, and

bids millions to watch replays of disasters like the

exploding of Challenger or the collapse of the Twin

Towers. During a big boxing match, crime rates drop

by 25% worldwide. It seems that everyone everywhere

can’t get enough of blood, gore and death, all

of which suggests that the regrettably retired Roman

Coliseum, as a state of mind, is enjoying an afterlife

that dwarfs that of the Nazarene’s now relegated

to the rites of Sunday school and cheerless Church ceremony.

The blunt

and brutal fact of the matter is that we, especially

men, like to watch things die, the slower the better,

and are prepared to spend considerable sums of money

for that very particularized pleasure. Like deer frozen

in bright headlights at night, we are fascinated by

death. As an autopsy-resistant event shrouded in mystery,

death is both the bewitching darkness at noon we cannot

refuse and gravitational force against whose escape

velocity the mind is no match.

We are a

species that hungers to know. We are wired to invest

our energies and three score and ten endeavouring to

make known the unknown, and when we succeed we are rewarded,

that is relieved of the fear and anxiety aroused by

the unknown. Our obsession with dangerous sports speaks

to that hunger. But since death is existentially unknowable,

we are fated to be left on the edges of our seats looking

into the abyss, into the cloudy eyes of the bull and

boxer on their way out – and no further. Like

Sisyphus condemned forever to roll the rock up the hill

only to have it roll down again and again, there can

be no final insight into death no matter how many bull

fights or boxing matches we attend.

Does the mystery of death recede the closer

we get to it, and like a feel-good drug over time, cause

us to require more of it for the same effect? The number

of new extreme and dangerous sports has increased exponentially

during the past 25 years, amplified by the proliferation

of cable and satellite TV that now broadcast potentially

lethal combat to the remotest regions of the planet.

Does the mystery of death recede the closer

we get to it, and like a feel-good drug over time, cause

us to require more of it for the same effect? The number

of new extreme and dangerous sports has increased exponentially

during the past 25 years, amplified by the proliferation

of cable and satellite TV that now broadcast potentially

lethal combat to the remotest regions of the planet.

Left to

our own devices, how many of us would rip up a ticket

to a man versus lion mismatch, or watch replays of "I

Love Lucy" while a public

hanging was taking place? What compels us to

sports where death is either a promise or a possibility

is not the inner savage having its way, but our insatiable

curiosity to know about death so to better prepare for

our own.

There is

much to be learned watching ourselves watching bulls

and boxers die or drop. For the occasion of the matador’s

final thrust, an inexpert estocado will puncture the

bull’s lung instead of the aorta. The animal,

bleeding at the shoulders and neck, vomiting torrents

of blood, will wobble, shudder, crumple and die. It

is the breathless, euphoric moment in the sport that

everyone pays for. In the case of the boxer who has

been bloodied, staggered and KOd, there is perhaps nothing

more satisfying in all of sport than watching the fighter

resurrect himself off the canvas and come back to fight

another round, a spectacle that rivals the comeback

around which Christianity was founded.

That we

are a "kinder and gentler" species is a proposal

the facts on the ground cannot support. With a nod to

Plato and observable human behaviour throughout the

ages, it seems that the mind is at the service of the

passions -- and not the other way around.

With all

due respect to the awe and humility I have experienced

in the presence of the great achievements in the arts

and humanities, it was while watching bulls expire in

the pools of their blood that left me feeling unprecedentedly

alive and vital, giddy and shaken and gasping for breath.

It was not Fra Angelico’s “Annunciation”

but bull’s blood that made me see that the enduring

truth of blood sport is revealed not in the ring but

in the collective response of the spectator for whom

the vicarious experience of death or near death produces

the opposite, animating effect. “The one thing

we seek with insatiable desire is to forget ourselves,

to be surprised out of our propriety,” writes

Emerson. In the sound and fury that borders on ecstasy,

which just happens to be the name of a drug, what is

invariable in the spectator response to near death moments

in sport is the obliteration of self-consciousness and

the rapturous light-headedness that takes over.

Whatever

medical indices one adduces to measure life potency,

in the presence of a blood fiesta a crowd’s numbers

go off the charts and into the adrenalinsphere, effectively

diminishing the predictive value of the law of diminishing

returns. Chiseled into the distorted, frenzied face

of any audience singularized by its fascination with

death is the understanding that all human endeavour

reduces to “the eternal recurrence of the same;”

meaning after the last bull has been killed, the last

boxer dropped, the enigma of death still remains, which

predicts that we shall not cease from knocking on heavens

door – until we gain entry.

No surprise

to observe that the rites of death are renewed and re-enacted

every day everywhere on the planet. And in those rooms

where people come and go, "talking of Michelangelo,"

well, my hunch is that they are just passing time waiting

for the next bull to be let out.

If the above

portrait is accurate in the way it speaks to what is

universal in the species response to lethal sport, and

makes us cover our eyes in shame, what can we do to

remake ourselves to better please the eye? How are we

to rise above the imperatives of our genotype? What

must happen to make us want to command ourselves to

stand still before the mirror and take into full account

what is there: an unhappy, confused, conflicted creature

whose slothful mind, thus far, has been no match against

the tried and tested straight-arm of human nature, "red

in tooth and claw."