BELIEVING IN JOHNNY CASH

by

PAUL WALLACE

______________________________________

Paul

Wallace teaches physics at Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Georgia.

He is also a regular contributor at Religion

Dispatches and blogs

for the Huffington Post.

It

has been pointed out that arguing doesn’t change people’s

views: “Hearts and minds don’t change that way.

They change when we share our stories.”

This

seems true to me, but I found myself wondering if a scientifically-motivated

atheist would feel the same way -- I have long suspected that

some atheists may be ill at ease with stories.

This

seems true to me, but I found myself wondering if a scientifically-motivated

atheist would feel the same way -- I have long suspected that

some atheists may be ill at ease with stories.

Before

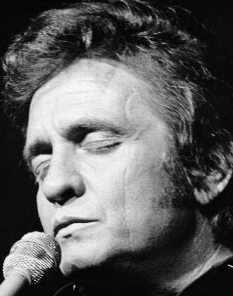

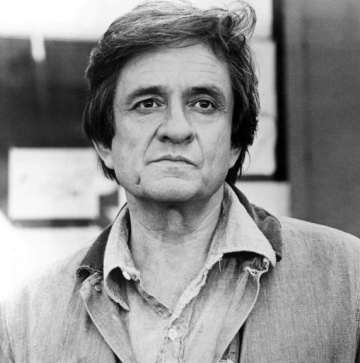

I say why, I need to say a few words about Johnny Cash, who

died on September 12, 2003.

WHY

JOHNNY CASH MATTERS

What

is your earliest musical memory? Mine is: One evening in about

1973 my dad put Johnny Cash’s “The Wreck of the

Old 97” on the turntable just before bedtime and let us

run fast around the den-living-room-kitchen loop. He turned

it up. We ran faster and faster as the nearly out-of-control

sound of Old 97 pushed us forward, wrecking finally in a joyous

three-child pile on the den floor. We did it again and again

until Dad finally sent us to bed.

Years

later, when I was in college, I found Dad’s old guitar

under his bed and pulled it out and began messing with it. Once

I began to play, what came out was not Led Zeppelin or the Replacements

or any other music I had listened to relentlessly throughout

my formative years, but the boom-chicka-boom of Johnny Cash

and the Tennessee Three. It was natural as a heartbeat. Cash

had gone in and he had stayed -- and every September 12 since

he died, I think of him.

Few

musicians have been as successful as Johnny Cash. In a career-spanning

six decades, he became more than a household name; he became

a legend.

What

was behind this success? It wasn’t his skill as a musician,

or his music industry savvy. It wasn’t even his voice

-- although few voices can match Cash’s for emotional

authority. I would argue that it was the stories he told. More

to the point, it was his telling of those stories with that

voice. His stories are humorous (“A Boy Named Sue”),

frighteningly violent (“Delia’s Gone”), darkly

romantic (“Long Black Veil”), playfully optimistic

(“Tennessee Flat Top Box”) and emotionally wrenching

(“Jacob Green”). Yet they all have something in

common: they are all simple, direct and palpably real.

It

was his own story that gave him authority to speak the truth.

“The Man in Black” was not a manufactured image,

but grew out of the story of his life. He was jailed seven times,

attempted suicide at least once, and was in and out of rehab.

Cash’s dark clothes and simple style marked the kinship

he felt with the imprisoned, the old, the destitute, the poor,

the forgotten. Without his own story, Cash’s music would

not be what it is: filled with the compellingly-told stories

of others.

Several

days ago I was in the car, listening to songs shuffled at random.

Just as I pulled into the parking lot I heard the opening lines

of “The Legend of John Henry’s Hammer,” recorded

at one of Cash’s famous 1968 Folsom Prison shows. Transfixed,

I sat and listened to the whole seven-minute song, which tells

the story of a man who, after winning a heart-pounding spike-driving

competition against a machine, lays down his hammer and dies.

It is a great story that may be read as a warning to those who

equate scientific and technological advance with human progress.

Several

days ago I was in the car, listening to songs shuffled at random.

Just as I pulled into the parking lot I heard the opening lines

of “The Legend of John Henry’s Hammer,” recorded

at one of Cash’s famous 1968 Folsom Prison shows. Transfixed,

I sat and listened to the whole seven-minute song, which tells

the story of a man who, after winning a heart-pounding spike-driving

competition against a machine, lays down his hammer and dies.

It is a great story that may be read as a warning to those who

equate scientific and technological advance with human progress.

What

I’d like to ask is this: do stories point us, in even

the smallest of ways, toward anything that might be described

as the truth?

WHAT

KIND OF TRUTH?

‘Truth’

is, of course, a dangerous little word. The truth I am talking

about is not something that can be formulated or systematized

or falsified. That is, I am not talking mainly about scientific

or literal or historical truth -- although the truth I am talking

about is related to those kinds of truth. Nor am I talking about

the truth of the fundamentalist, religious or otherwise. The

kind of truth I am talking about cannot be used as a weapon.

It cannot be used by any debate team. I am talking about the

truth of stories, when, for better or for worse, you can’t

really get a good fix on their truth.

An

illustration may prove helpful. As an astronomy professor I

spent many nights under the night sky with my students, pointing

out stars and planets and galaxies. And they would regularly

strain and squint, trying to see dim stars I could see easily.

This is not because they were blind or my vision was excellent,

but because there’s a trick to it. The thing is, to see

a dim star you can’t look straight at it. But once you

relax and look a little to the side of it, it pops clearly into

view. Of course once this happens you reflexively focus on it

again in an attempt to see it even better, but when you do --

poof -- it disappears.

It’s

very frustrating to novice sky gazers, but once you get the

knack of it, it’s nearly automatic. This is what the truth

of stories is like: the harder you try to focus on it, the more

elusive it gets.

There

are small truths and there are big ones. And in my view (it

is perhaps more of a hope) all the truths are somehow related

to all the others. Somewhere in there, maybe containing them

all somehow, is ‘the’ truth, whatever it is. This

biggest truth is reality. It’s what’s true about

us, about God if there is a God, about death, about life. Whatever

this bottom-level truth is, I like to think that all lesser

truths hold our interest only insofar as they are related to

it.

SUE

AND HIS OLD MAN: ONE SMALL TRUTH?

In

1969 Cash recorded a song called “A Boy Named Sue.”

In it, he tells the story of a three-year old child whose father

abandons the family, leaving the boy with the name ‘Sue.’

As

the song unfolds, the boy named Sue grows into a man named Sue.

The name ensures that along the way, Sue gets laughed at and

bullied. It ensures that his “fists get tough and [his]

wits get keen.” Sue roams from town to town in search

of old Dad, looking for revenge. Eventually he catches up with

him in a Gatlinburg bar and throws himself onto him with all

the stored-up fury of a lifetime.

As

the song unfolds, the boy named Sue grows into a man named Sue.

The name ensures that along the way, Sue gets laughed at and

bullied. It ensures that his “fists get tough and [his]

wits get keen.” Sue roams from town to town in search

of old Dad, looking for revenge. Eventually he catches up with

him in a Gatlinburg bar and throws himself onto him with all

the stored-up fury of a lifetime.

Just

as Sue has his father in his gun sights the old man looks at

him, smiles, and explains that he gave him the name to make

him strong. After all, his father knew he wouldn’t be

around to teach him anything. He figured if he survived with

a name like that he’d be strong indeed. In

the last verse of the song Sue recalls,

I

got all choked up and I threw down my gun

And I called him my pa, and he called me his son,

And I came away with a different point of view.

And I think about him, now and then,

Every time I try and every time I win,

And if I ever have a son, I think I'm gonna name him

Bill or George! Any damn thing but Sue! I still hate that name!

The

humor here is delivered atop a dark urgency -- there’s

more here than laughs.

Or

is there? When you find yourself captivated by a song like “A

Boy Named Sue,” is it because it points you toward the

truth about real fathers and sons? If so, perhaps one small

truth contained in Cash’s song may be expressed: Fathers

always come to fear their sons.

Freud

may nod approvingly, but does this small truth (if it is indeed

true) stand on its own, cut off, independent of all else? Or

might it, if we dwell on it and ask some questions about it,

take us to other truths -- perhaps bigger, perhaps smaller --

about the world? Or is it related only to mere neurons and chemical

reactions and so makes us laugh for a time but is ultimately

about nothing at all?

And

if you think this is the case (and here I’m addressing

myself to my confirmed atheist readers) -- that the only true

truth is energy and matter in motion -- how did you come to

believe that? I’m betting that you came to believe it

because you believed in the truth of another story.

THE

TRUTH OF STORIES – OR NOT

I should

also make clear what I mean by stories. Stories are not ‘just

the facts.’ In fact, that is precisely what they are not.

For

our purposes, the facts are the empirical facts of science:

evolution, the big bang, genetics, geology and physics. These

theories and disciplines are about the facts. Not in a simple

way, granted, but in the same way that economics is about dollars

and cents. The best science is securely grounded in empirical

facts.

So

far as I can tell, (and again, addressing my atheist friends)

the scientifically motivated among you believe that, in the

end, empirical facts are all the truth we can ever have. And

this is so not because science is limited but because, in the

end, facts are all there are. Put another way, if one wants

anything that goes by the name of truth (as opposed to feelings

or hunches or anecdotes or just plain guesses) then one must

not venture beyond the circle defined by the (current) frontiers

of science.

Beyond

that circle lies everything from weeping statues of Mary and

the resurrection of the dead to Sasquatch and alien abductions.

It is a land of phantasms and superstitions of the grossest

kind and has nothing to do with reality. Reality lives exclusively

inside the circle of empirical facts and the sciences that build

on them. And since God does not reside within that circle, God

has nothing to do with reality. I hope this is a fair representation

of scientifically motivated atheism.

If

facts are what define that circle, stories are what is added

to the facts. Stories take you outside that circle. In my use

of the word, stories are interpretations of the facts. (Therefore

scientific theories, being interpretations, are themselves stories

of a kind. But I am thinking of interpretation in the less radical,

more colloquial sense of the word).

What

I propose is that no one lives, or can live, or has ever lived,

within the circle of empirical science. I propose that no matter

who we are or what our beliefs might be, we have always had

to deal with the question of interpretation. And that question

is not whether to interpret, but ‘how.’ No one fails

to interpret. Interpreting is what human beings do.

Put

another way, we cannot avoid believing in stories. We can only

hope to choose the best ones. How to do this? I propose that

good stories are stories that tell the truth, and bad ones are

ones that do not.

I fear

that I may have lost some of you just now. In particular, most

atheists I know would be quite critical of the idea that stories

are related in any meaningful way to the bedrock truth about

the world. So in the interest of keeping everyone on the bus,

let’s back up and assume that the stories we tell are

unrelated to anything that could pass as true.

Some

atheists take this assumption -- that stories are not meaningfully

related to the truth -- and run with it. But when they do they

immediately leave behind the circle of empirical science by

making up stories of their own. Here’s a dazzling example,

blogger PZ Myers on the metaphor of God the Father:

Christians and

Muslims and Jews have been told from their earliest years

that God is their father, with all the attendant associations

of that argument, and what are we atheists doing? Telling

them that no, he is not, and not only that, you don't even

have a heavenly father at all, the imaginary guy you are worshiping

is actually a hateful monster and an example of a bad and

tyrannical father, and you aren’t even a very special

child -- you’re a mediocre product of a wasteful and

entirely impersonal process.

We’ve

done the paternity tests, we've traced back the genealogy, we’re

doing all kinds of in-depth testing of the human species. We

are apes and the descendants of apes, who were the descendants

of rat-like primates, who were children of reptiles, who were

the spawn of amphibians, who were the terrestrial progeny of

fish, who came from worms, who were assembled from single-celled

microorganisms, who were the products of chemistry. Your daddy

was a film of chemical slime on a Hadean rock, and he didn’t

care about you -- he was only obeying the laws of thermodynamics.

Now,

this is a story just as surely as any other. Don’t get

me wrong -- I don’t for a moment doubt the basics of evolution

and thermodynamics. But Myers was not forced by the facts of

nature into these beliefs he so forcefully espouses. Instead,

he has done exactly what storytellers do: He has told us a story.

That is to say, he has added his own stuff.

The

problem is that not that Myers is telling us all a story, but

that he insists he is not. “Reality,” he writes,

“is harsh.” His story is the story you absolutely

must believe if you absolutely insist on not believing in stories.

Most

stories are spiced with irony, but not this one. Here, irony

is all you get.

LIVING

WITH STORIES IN AN AGE OF IRONY

Just

a moment. I’d like to fill my lungs with some blissfully

unironic air and speak plainly about stories. Because to believe

in the truth of stories is to, at least for a moment, abandon

our ironic reflexes and accept the possibility of genuineness.

I am

a Christian. Why? Because I find the stories Jesus tells --

his parables -- to be compelling. They speak not only to my

greatest joys and hopes but to my frailties and fears. They

resonate powerfully with what I believe to be my deepest self.

But there is more; like Johnny Cash and his songs, there is

truth to be found not only in the stories told by Jesus the

storyteller but in the story of Jesus the storyteller.

And

like Johnny Cash, Jesus has some things to tell us about fathers.

For example, there is the father who, at his son’s request,

gives him his full inheritance early. The boy immediately squanders

it, lands in the gutter and ends up looking hungrily at pig

slop. In the words of Presbyterian minister Frederick Buechner,

writing here from the prodigal’s perspective,

There

wasn’t anything to do that I had not done. There wasn’t

anything to see that I had not seen. There wasn’t anything

to lose I hadn’t lost. I envied the pigs their slops because

at least they knew what they were hungry for whereas I was starving

to death and had no idea why. So I went back [home. And when

I did] he held me so tight, I could hear the thump of his old

ticker through his skimpy coat.

So,

Jesus tells us, the prodigal comes back home in shame and is

welcomed as the beloved, the guest of honor.

Can

we really live with such a story in an age of irony? It is not

easy, for it is in our bones to pass it off as a sweet heartwarming

tale made to comfort us in the darkness of a cold and meaningless

universe. That is what it is, and nothing more. So our citified

and suspicious selves conclude.

But,

if we are able to check our self-conscious impulses just long

enough, might this story reach us as an echo of a hint of something

really real? If not about God, then maybe about fathers and

sons? On my best and most unironic days I think so.

Irony

is good. It can be magical in small doses. All the great storytellers

know this. What could be more ironic than a steel-fisted fighting

machine named Sue? What could be more ironic than a rich boy

pining for pigs’ food? But irony is like curry or ginger,

made to give a story bite and astringency, and can’t be

the whole meal.

If

you cannot accept that stories may have something to do with

what’s really real, you end up with a single-ingredient

offering of solid irony. That is, you end up with the story

based on the premise that all stories are false. That galling

story, the necessary and logical result of seriously not taking

stories seriously, just isn’t good enough.

More

importantly, this doesn’t match life as I know it and

live it every day. Nor, I dare say, does it match the lives

of anyone who has ever lived. Is this not a piece of evidence

worthy of consideration?

If

you think not, if you think there’s nothing about stories

that relates to the actual truth of things, I’m not sure

how you get through your days. I really don’t. I am not

making a joke. How can you remain fully committed to whatever

story your own human subjectivity has latched onto, knowing

all the while there’s nothing there? Is it possible to

live happily on a diet of solid irony?

And

that’s an honest, non-rhetorical, one hundred percent

irony-free question.

The

following is reprinted with permission from Religion

Dispatches. You can sign up for their free daily

newsletter here.