why there are

TOO MANY BOOKS

by

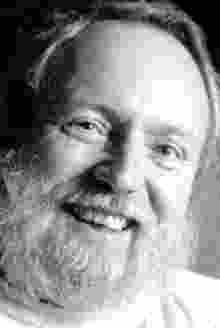

MICHAEL RUSE

_________________________________

Michael

Ruse is a philosopher of biology at Florida State University

and is well known for his work on the creationism/evolution

controversy and the demarcation problem in science. He is the

author of many articles and books including Darwin and its

Discontents (2006).

Quick.

Take my temperature. I must be sick. I am in danger of agreeing

with Naomi Schaefer Riley!

If

you can peer through the thick fog of animus towards university

professors and what they do, she has an important point about

academics and books. There are too many books being published,

or at least there are too many of the wrong kind.

Frankly,

speaking now of my own field of philosophy, there really are

way too many technical monographs, read by vanishingly few.

We philosophers think that to be profound we must be prolix

and complicated – think Immanuel Kant – and we rather

revel in it. It is not so much that our topics are inherently

boring, but that we fear that unless what we write is boring,

no one will think us deep and thoughtful.

There

is a possibly apocryphal story (but one of those stories that,

even if it isn’t true, ought to be true) about the important,

American, 20th-century philosopher Wilfred Sellars. Talking

to him, he was fun and interesting and comprehensible. But then

he would put pen to paper. He would start with a first draft

that anyone could understand, and (this completed) set to again.

At length he would be faced with a manuscript comprehensible

only to God. Happily, he would set out for one final set of

revisions.

Actually,

speaking now as one who has edited books for Cambridge University

Press for 20 years, the market is starting to rectify this situation.

(Is this the Invisible Hand at work? Tell the New Atheists.

Ruse has a new proof for the existence of God). When I started

editing a series in the philosophy of biology around 1990, we

could expect to sell around 2,000 copies. Not God Delusion

numbers, but respectable in academic circles.

Over

the next 15 years, this drifted down and down to about 500 copies.

I am told that it was nothing personal, but a general trend

of philosophy books. So now we have revanched, and launched

a new series aimed more at students and the general reader.

The initial books strike me as just as deep and thoughtful as

the older books (in some cases written by the same authors)

but much more interesting and fun to read. I am going to be

seriously cheesed off if we don’t sell 3,000 copies a

shot.

But

the place where I really agree with my fellow Brainstormer is

over books by young academics. It is not a disease that affects

people in the sciences. No serious, untenured faculty member

in physics is going to write a book. Get on with the articles

and show your mettle. I am glad to say that this is also the

way in philosophy. I don’t think I am alone in distrusting

books by young philosophers. It is almost invariably a warmed-over

dissertation and as such not a real book. Much better to cut

your teeth on articles. Apart from anything else, it is here

that you start to get the real feedback on your work. Up to

now, everyone from your mom to your supervisor has been telling

you how great you are and then some nasty, little, unwashed,

anonymous referee rips you up. If you have any good sense, you

will get drunk, swear at the referee – obviously just

out of grad school, doesn’t know the literature, jealous

at what you have written – and then settle down and take

the criticisms seriously.

(Actually,

as one who has also founded and edited a journal for 15 years,

I am being very unfair to referees. My experience was that senior

scholars particularly would spend hours on the work of the most

junior authors. I, for one, think blind refereeing is stupid.

I want to know the background against which a piece is being

written and I found that people worked really hard to see merit

in unknown people. Remember, an editor or referee gets much

more credit for finding the new Immanuel Kant than for publishing

the established Immanuel Kant’s latest piece on the Categorical

Imperative).

Unfortunately,

in many areas of the humanities – English and history

are the big sinners – the demand is for a book for tenure.

And so we get volume after volume that would have made one or

two good articles, and put the rest of the material on the Net

if it is worth knowing about. Readers get cheated because they

are not getting value for money and authors get cheated because

they are not getting the right feedback (and the discipline

of writing clearly and concisely) at the very time they need

it most.

My

suspicion is that the Invisible Hand is moving in here too.

Presses, particularly academic presses, are under huge monetary

constraints and less and less will be able to publish a monograph

that sells 300 copies. Universities won’t buy them. And

a young author can only afford so many copies to give to relatives.

So the opportunities to publish these unneeded books will fade

and humanities departments will simply have to make other demands

for tenure.

Who

says the market is always a bad thing? Not me or Ms. Riley,

I am sure!

PS:

I am being atypically modest. With a topic like this, even despite

the somewhat chilly and mystifying cover, if I don’t sell

10,000 copies I am going to be very cross. Keeping things in

perspective, when I last heard, The God Delusion had

sold over three million copies.