Lola

played at Montreal's 2010 Festival du nouveau cinéma.

Ron

Wilkinson, who writes for monstersandcritics.com,

gave the film 3.0 out of 4. For

festival ratings, click HERE.

Not the knockout

punch of his previous Kinatay or Serbis

but an unvarnished look into the inner-workings of a world

forced to brutality.

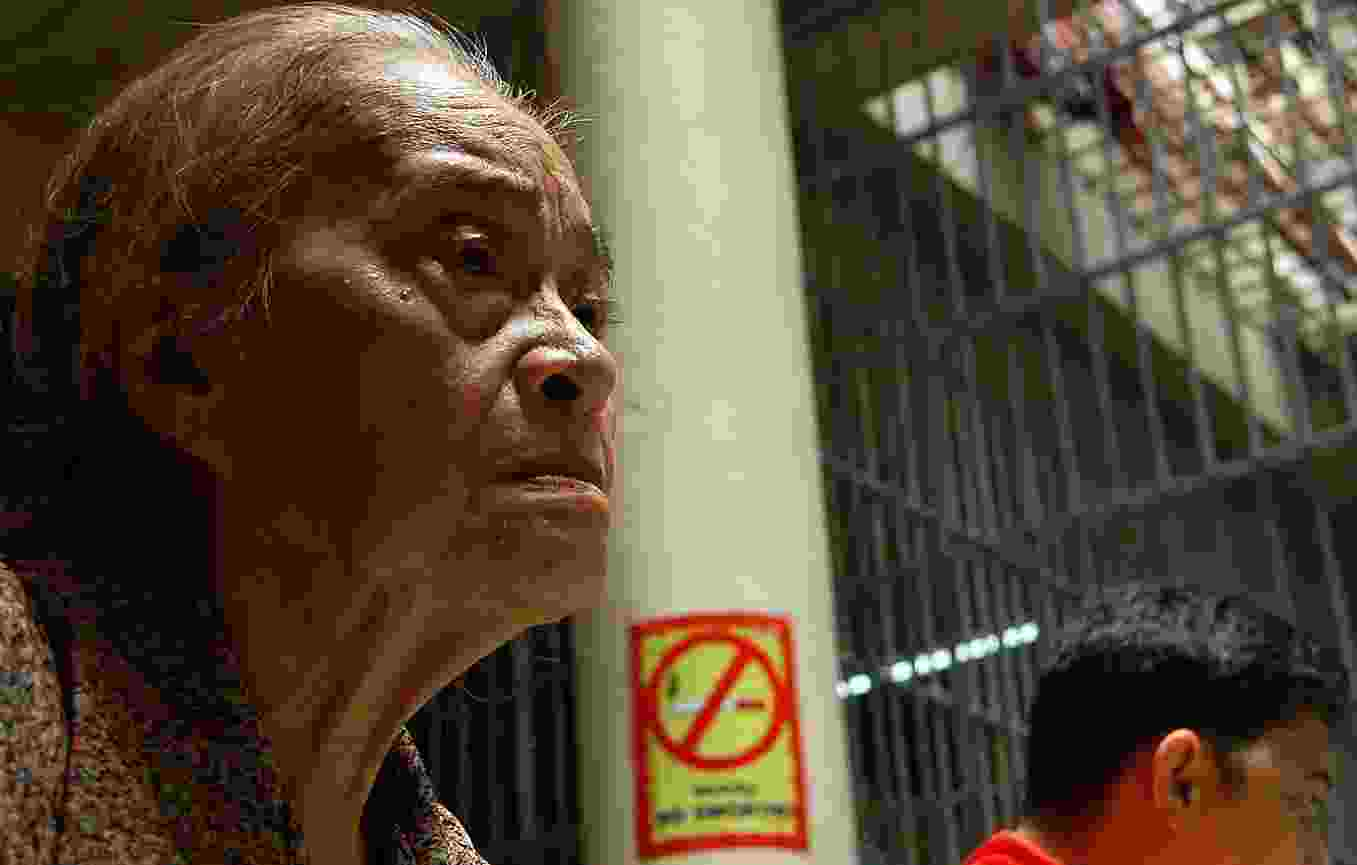

Lola

(the Filipino word for grandmother), the third major work

of Cannes auteur Brillante Mendoza, had big shoes to fill.

It had to match the simmering anger and seething underbelly

pungency of Serbis and Kinatay. Although

it may lack some of the raw energy of those films, it brings

a dialog about right and wrong to the screen that has never

been said better.

Lola

(the Filipino word for grandmother), the third major work

of Cannes auteur Brillante Mendoza, had big shoes to fill.

It had to match the simmering anger and seething underbelly

pungency of Serbis and Kinatay. Although

it may lack some of the raw energy of those films, it brings

a dialog about right and wrong to the screen that has never

been said better.

The

film starts with the tragic death of the lola's grandson

by stabbing. As the report goes, the teenager was killed for

his cell phone in the violent suburbs of Manila. The viewer

knows there was probably more to this than was included in

the initial report, but a suspect is apprehended and put into

jail. The movie starts with the aggrieved grandmother fumbling

through the squalor and danger of the roughest barrios in

the world to scrape together the resources for a funeral.

The ceremony will be the most expensive thing she has ever

purchased. It is by far the saddest.

As

this proceeds, nickels and dimes at a time, the accused is

introduced. Although he is intially depicted as a violent

and disturbed young man, his humanity is brought to the surface

as the crime itself recedes into the background. His grandmother

becomes as much the focus of the story as the grandmother

of the deceased. While the latter works every angle in the

poverty-stricken ghetto to buy a casket, the former seeks

first justice for her grandson and then works towards the

recommended amicable settlement.

The

amicable settlement consists of an apology and a payment of

a sum of money to the grandmother of the victim. As this story

unfolds the audience is treated to two profoundly meaningful

stories. The first story is about a grandmother saving her

grandson from prison that is tantamount to a death sentence.

The second story is the struggle of the bereaved to accept

the heartfelt apology of the family of the perpetrator and

the cash settlement instead of demanding the pound of flesh

that is their right by law.

The

concept of buying freedom for a man assumed to be guilty of

homicide will catch many off guard. Things are not done that

way in North America. At least they are not supposed to be

done that way. But America has prisons where inmates survive

and are sometimes even rehabilitated. In the Philippines and

many other countries, a sentence in prison of five years is

a death sentence unless the family keeps a constant supply

of food coming and the prisoner is strong and a skilled fighter.

The odds of survival are miniscule.

The

story turns out to be about acceptance and forgiveness instead

of being a mystery thriller about collaring the criminal.

The implied lesson is that we are all capable of criminal

acts if we are pushed far enough. As we see more and more

into the family life of the killer we learn that they are

starving because road construction has crippled their hand-cart

based transportation business. They are losing their meager

possessions one by one as they struggle to support a son who

is himself the victim of birth defects.

Great

cinematography of monsoon rain as the watershed decisions

of life and death come to pass. The barrio is on the water

and the funeral is even held in boats on the water.

In

the end the two matriarchs have the fateful meeting in which

they join in their sorrow and their hope for the future and

do the best they can. The fact that they do it outside of

the law is significant. Forgiveness and healing are not legislative

mandates; they are practical remedies for the inherently predatory

nature of humankind.

Mendoza

gives another solid and commendable work, finding beauty in

the ugliness of the human condition.

Directed

by: Brillante Mendoza

Written by: Linda Casimiro

Starring: Rustica Carpio and Anita Linda