He served two

terms as president of P.E.N., the international organization

of writers and editors.

There was an award

from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and teaching

stints at Princeton and Yale, but Kosinski's renown extended

beyond the written word.

He was a 12-time

guest on Johnny Carson's "Tonight Show."He

played a small but significant role in the movie Reds,

directed by his friend Warren Beatty (he got billing over

Jack Nicholson).

He would have

been at the Beverly Hills home of another Hollywood friend,

Roman Polanski, on the night that Polanski's wife Sharon Tate

and four others were murdered by members of Charles Manson's

"Helter Skelter" family; but, on his flight from

Paris to Los Angeles, his luggage was unloaded by mistake

in New York, which delayed him by a day.

He posed half

naked for the cover of The New York Times Magazine.

Away from the public spotlight,

at dinner and cocktail parties held in New York penthouses,

Kosinski was on a first name basis with the famous –

Henry Kissinger, fashion designer Oscar de la Renta, theatre

critic John Simon, Senator Jacob Javits – and also with

those anonymous bankers and industrialists whose decisions

drive the world's economy. He was often the center of attention,

for he had the gift of beguiling.

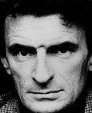

His appearance was striking.

His face was framed by a dense mass of tightly-curled black

hair. His eyes, under wizard-like brows, were large, black

and bright. His nose had the hook of a predatory bird's beak.

His mouth, unusually long and thin, seems, in photographs,

to be clamped shut like an oyster shell.

But that mouth

opened, and out came exotic stories told in an exotic accent.

Accounts of his adventures in the cryptic world of communist

Poland and the Soviet Union, chilling tales of his childhood

in Nazi-dominated Eastern Europe, stories about his visits

to sex clubs that catered to every desire.

Kosinski was a

kind of emissary, one dressed in suit and tie, bringing dispatches

from life's underbelly. Yet he did it with a raconteur's wit,

and he always retained a sense of mystery. Did he participate

in the sexual circus he described or was he just an observer?

In all his stories, what was truth, what was made up?

Despite his free-wheeling

lifestyle, Jerzy Kosinski had a wife. She did not accompany

him on his night time prowls (other women did), but it was

entirely due to her that he was in a room entertaining the

affluent and powerful.

Before the marriage

he had been an academic studying social psychology and had

written two books of anti-communist essays under the pseudonym

of Joseph Novak. Mary Hayward Weir, the widow of an industrialist,

admired his writing, which led to their first meeting. She

employed the young man to catalogue the books in her library.

When they married

Jerzy was 29, Mary 47.

Kosinski was suddenly

part of a world that included a Park Avenue duplex, homes

and vacation retreats in Southampton, London, Paris, Florence.

There were servants, a private jet, a boat with a crew of

seventeen. And, of course, those parties.

The marriage ended

after four years (two years later Mary died of brain cancer).

Though his life of opulence was over, he had published The

Painted Bird, and thereafter his writing provided him

with a substantial income. He traveled extensively, skied,

played polo.

Shortly after

Mary Weir's death, Kosinski began a relationship with Katherina

(Kiki) von Fraunhofer, a descendent of Bavarian aristocracy.

After 20 years together, they married; four years later, in

1991, Jerzy Kosinski committed suicide. He was 57.

THE FALL

Eight years before

he got into a bathtub and put a plastic bag over his head,

the writing career of Jerzy Kosinski had been fatally damaged.

The first blow came in the form of a Village Voice

articled entitled "Jerzy Kosinski's Tainted Words."

Three

major accusations were made.

One

was that Kosinski didn't deserve credit as the author of his

books. Someone came forward claiming that he had written The

Painted Bird; others said that Kosinski wrote it in Polish

and that the translator had not been acknowledged. As for the

seven episodic novels that followed, it was alleged that Kosinski

provided the ideas but editors did the actual writing; the books

were, in effect, ghostwritten.

Another

accusation was plagiarism -- that Kosinski filched the concept

and structure of Being There from a 1932 Polish novel

entitled The Career of Nikodem Dyzma by Tadeusz Dolega

Mostowicz.

The

third accusation was the most damning. Kosinski had always insisted

– at parties, in interviews, in writing – that he

was the boy in The Painted Bird (which, he said, was

not strictly a novel but was "auto-fiction"). This

nameless boy, who has black hair and black eyes and is thus

suspected of being a Jew or a Gypsy, is six when World War II

breaks out. He wanders from village to village. In the first

printing the locale is central Poland, but in every subsequent

edition it is Eastern Europe. For four years he is witness to

and victim of horrific cruelty and barbarism – committed

not by the Nazis but by peasant villagers, who are superstitious,

ignorant and brutal. After being thrown into a pit of excrement,

in which he nearly suffocates, the boy loses the power of speech.

At the end of the novel he regains it.

Poles

who read the book were highly indignant about how they were

depicted (for 23 years the novel was banned in Poland). Then

accusations from Polish researchers began to emerge. Kosinski's

story was a lie. He had not suffered atrocities at the hands

of Polish peasants. Instead, he and his family had lived through

the years of Nazi occupation not only in safety, but in comfort.

And their protectors? – Poles.

Documents,

personal accounts and even photographs were produced. In the

Polish version, the Jewish Lewinkopf family, to escape the Nazis,

moved from Lodz (where the Lodz ghetto and the nearby Chelmno

Extermination Camp would claim hundreds of thousands of Jewish

lives) and changed their name to Kosinski, a common Polish one.

They lived in the homes of Poles and their true identity was

concealed by Poles. They carried on their lives as Catholics.

Jerzy was baptized and received Holy Communion; he served as

an altar boy. The Lewinkopf/Kosinski family was in fearful hiding,

but not in a potato cellar or barn. They even employed a maid.

The

Poles branded Jerzy Kosinski a Holocaust profiteer because the

novel, which drew critical comparison with The Diary of

Anne Frank, was immediately granted the status of a chronicle

of the Holocaust.

But

Anne Frank was in that attic. If you take away the authenticity

of The Painted Bird, what is left?

TRUTH

Truth

can be elusive. The information about Kosinski's rise and his

years of success should be fairly accurate, since it is a matter

of public record or comes, undisputed, from multiple sources.

But the accusations that precipitated his fall present problems.

I encountered so many contradictory and questionable "facts"

that everything I read became suspect. I began to believe nothing.

Truth

can be elusive. The information about Kosinski's rise and his

years of success should be fairly accurate, since it is a matter

of public record or comes, undisputed, from multiple sources.

But the accusations that precipitated his fall present problems.

I encountered so many contradictory and questionable "facts"

that everything I read became suspect. I began to believe nothing.

Kosinski

– the man who, according to both friends and foes, liked

to operate from behind smoke and mirrors – was no help

in clearing up matters. One example: When he writes about his

relationship with Mary Weir, what emerges is a picture of a

devoted couple separated only by her tragic death. Why does

he omit the fact that they divorced? Could it be that he did

not want his marriage to a wealthy socialite 18 years his senior

to be perceived as a career move? Reading Kosinski on his personal

life, I constantly sensed I was being steered in a direction

that suited his purposes.

I consulted two highly-respected texts. Contemporary Authors,

published by Gale Research, relates the story of how Kosinski,

as a boy, lived through the experiences depicted in The

Painted Bird, while American Writers (edited by

Jay Parini) bluntly states that Kosinski lied about his wartime

experiences; he was safe with his parents. Two teams of "experts,"

working with the same information, came to opposing conclusions.

At

this point I decided to take a different approach in this essay

– a personal one. Though my emotions will come into play,

they will be in response to Kosinski's work, not to the man.

I'll rely on simple logic, and for my texts I'll use the novels

he wrote (or didn’t write).

The

easiest accusation to tackle is the one about plagiarism. I

believe that a Polish novel entitled The Career of Nikodem

Dyzma exists, but I find no indication that it was translated

into English. So I cannot compare it to Being There.

Still, how could a novel written in Poland in 1932 correspond

closely to the adventures of Chauncey Gardiner (a.k.a. Chance

the Gardener) in New York in the 1960s? Television had not been

invented in 1932; Chance is a product of television. He moves

into the lofty realms of corporate wealth. Being There

remains strikingly relevant to the media-driven America of 2007.

Kosinski may have borrowed the premise of the idiot whose simpleminded

utterances are interpreted as profundities, but he had to considerably

shape this premise to fit his purposes.

Did

Kosinski write his novels? I came across no solid, unassailable

proof that he didn't: only people making those claims and others

refuting them (some being editors stating that they did nothing

more that normal editorial work on his books). We do have Kosinski's

admission that he was not only very receptive to editorial advice,

but that he actively solicited help. He would send copies of

a novel-in-progress to friends, asking them to mark places that

"didn't sound right" (he lacked confidence in his

command of the English idiom). He was a compulsive reviser.

In his 1972 Paris Review interview there is a facsimile

of a galley proof page of Passion Play with Kosinski's

handwritten changes. A note states that, between the first and

third set of galley proofs, he shortened the novel by one third,

cutting over 100 pages. This can be seen as a sign of insecurity.

But insecurity is no fault – not if it motivates the writer

to work hard to get it right.

I find

Kosinski's novels to be stylistically similar. The prose is

detached, flat, terse, and it has an emotional remoteness that

is unique. The voice of the novels comes across as that of one

person.

Next

we move to the thorniest accusation. Even though documents,

personal testimonials and even photographs have been produced

by Polish researchers which "prove" that Jerzy Kosinski

spent his boyhood in safety, I had my doubts. Documents can

be forged, personal accounts can be fabricated, old photographs

of a black-haired boy do not constitute evidence. Could resentment

about how Kosinski depicted the Polish peasant have led to a

campaign to discredit his book?

On

the other hand, those who see The Painted Bird as a

realistic portrayal (the words "brutal truth" are

often used in reviews) may be predisposed to accept as true

that which isn't. We expect monsters when we think about Europe

in the throes of World War II, and Kosinski provides them in

abundance. That these monsters are not jack-booted Nazis would

seem to undermine the Holocaust connection. The explanation

given by his supporters is that Kosinski's broad theme was the

victimization of the powerless; if the evildoers in this firsthand

account were peasants in Poland, so be it. Kosinski's comments

on the novel's title corroborate these arguments. He states

that he witnessed, as a child, a favorite entertainment of villagers.

They would trap a bird, paint its feathers vivid colours, and

then release it. When the painted bird returned to its flock

the other birds attacked and killed it.

The

first time I read The Painted Bird, I was unaware of

these complexities. I believed that the book was a fictionalized

account of events which the author had actually experienced.

But as I moved from one gruesome scene to another I lost that

belief. A gut feeling grew, and a strong one. These things never

happened.

In

chapter four a miller gouges a plowboy's eyes out with a spoon.

In chapter five a mob of women attack a character named Stupid

Ludmila; one of them pushes a bottle filled with excrement up

her vagina and kicks it so that it breaks; then they beat her

to death. In chapter six a carpenter is devoured by rats.

Any

one of these horrors might be accepted as the truth, but the

stringing together of one after another (and many more follow)

is highly suspect. I came to believe that I was reading the

fantasies of a sick mind.

All

this is done artfully. Kosinski establishes a pervasive sense

of dread; he builds up to each event with deliberation; he describes

it with imagery that penetrates deep into the reader's consciousness.

I am not questioning the power of the writing. I am questioning

its morality. Detractors have called the novel pornographic,

contending that it excites a form of lust. Some act out that

lust, in basements with bloodstained concrete floors. Marauding

armies seem to be infected with it. Leaders of countries have

conducted reigns of terror based on it. It’s a deplorable

but undeniable part of the history of man. And, as a confirmation

of its existence in the here and now, there are writers and

filmmakers who make millions by providing grisly fare to a public

that wants to vicariously enjoy it. Kosinski recognized that

his novel had this appeal. In an interview conducted seven years

after the novel was published, he talks of readers who "pursue

the unusual, masochists probably, who 'want' sensations. They

will all read The Painted Bird, I hope."

But,

as befits the man, Kosinski's literary ambitions were extravagant.

If The Painted Bird was to be considered a serious

work of art, he knew that its sensationalistic aspects must

be overshadowed. What redeeming element could raise it above

its parade of repellent scenes? How could he get a reputable

publisher to consider the novel? The solution was something

an expert dissembler like Kosinski was well-equipped to carry

off. What greater significance, what greater validation could

he bestow upon the novel than to claim it to be the truth?

At

parties held in Mary Weir's penthouse, Kosinski told stories

of his childhood during the war. Since these parties were well-represented

by the artistic set, people in publishing were present. It is

easy to imagine Kosinski taking a senior editor aside -- suddenly

serious, his black eyes intense – and confiding that the

stories weren't fabrications, that they had actually happened

to him. And more, much worse than anything he had spoken of.

But he had written about these things. It was something he was

compelled to do, to tell it all.

Executives

at Houghton Mifflin promoted the book as a true account of what

the author endured, and it was widely accepted as such by critics,

most of whom gave it extravagantly glowing reviews. With his

first novel, Kosinski had reached a pinnacle.

Stripped

of its authenticity, The Painted Bird is still a Holocaust

novel. It is not about the acts of peasants but about the damaged

psyche of Jerzy Kosinski. I believe that as a boy he hid in

comfort, but he was still hiding from monsters. Hiding from

the trains that took Jews to extermination camps, where they

were herded into ovens. Of these things he surely knew, and

they haunted his thoughts.

The

cover of my Bantam edition of The Painted Bird shows

a detail from the Hell panel of Hieronymus Bosch's "The

Last Judgment." The painting is crowded with grotesque

tortures that fascinate and repel. But was Bosch ever in hell?

Did he witness what he depicted? We are seeing the same type

of sickness that afflicted Kosinski, though Bosch's was religiously

motivated. There is no indication that Kosinski had any religious

beliefs. He may have worshiped power. It would have been one

of the childhood lessons he absorbed into his blood and bones,

along with lessons about the need to lie, the need to hide.

But power was most important. It is the prevailing theme of

his work. Steps, his second novel, is composed of brief,

disconnected episodes that portray variations on the relationship

between victim and victimizer. Brutality is present, though

not nearly to the intensity as in The Painted Bird.

In Steps the means of subjugation are mainly psychological.

The

Painted Bird can be seen as an exercise in power. It is

an attack on the reader's sensibilities. It is also an act of

seduction, for Kosinski entices the reader into complicity with

his dark inner world. As the miller twists the spoon in the

plowboy's eyes, we are made both victim and victimizer.

ETERNITY

The

1982 Village Voice article and the swirl of controversy

that followed it marked the end of the literary career of Jerzy

Kosinski. The string of novels that he was producing every two

or three years came to a halt. One more book, The Hermit

of 69th Street, was published six years after the article

appeared. It was long (over 500 pages) and was about an author

besieged by false accusations. It quickly sank into obscurity.

The

1982 Village Voice article and the swirl of controversy

that followed it marked the end of the literary career of Jerzy

Kosinski. The string of novels that he was producing every two

or three years came to a halt. One more book, The Hermit

of 69th Street, was published six years after the article

appeared. It was long (over 500 pages) and was about an author

besieged by false accusations. It quickly sank into obscurity.

Whatever

Kosinski felt inwardly, he did not live the life of a hermit.

He devoted much time and energy to social and humanitarian causes.

He worked for the creation of the Jewish Presence Foundation,

aimed at "empowering" Jews. He also was involved with

the establishment of AmerBank, the first Western bank chartered

in post-communist Poland.

He

still had money; he still traveled; he still had friends. It

is fitting that Kosinski’s last night was spent at a crowded

party in an Upper East Side townhouse. Fitting because that's

where his life of fame and fortune began.

The

party was given by the author Gay Talese. According to The

New York Times, Talese detected no signs of depression.

"Last night, he was moving in and out of the crowd as I've

seen him on so many occasions."

Kiki

told police that she had last seen her husband at 9 p.m., before

he left for the party. The next morning she found him in his

bathroom (they had separate bedrooms and bathrooms). He was

naked in a tub half-filled with water, a plastic shopping bag

twisted around his head. She said that he had been depressed

about a heart condition. He had left a note in his office. In

it were these words: "I am going to put myself to sleep

now for a bit longer than usual. Call the time Eternity."

In

researching his death, I again came across conflicting reports:

the seriousness of his heart condition is definitely in doubt;

some accounts of his suicide include barbiturates washed down

with alcohol.

In

the end, I don't understand Jerzy Kosinski. At some level, he

must have judged his life as successful. Using his talent, wits,

boldness and determination, he went far, if you consider the

boy growing up under the most menacing of shadows. Was he happy?

There is so much darkness in his novels, I wonder how much brightness

there was in his life (inside him, in the place he kept hidden).

I am left with a sense of pity, which I'm sure he would not

want me to feel. He would prefer respect. And I can grant him

that.

In

the last moments of his life he again displayed an indomitable

will. For Jerzy Kosinski, old age, with its frailties and loss

of independence, was something he chose not to deal with. He

'chose.' He acted. He would not be a victim -- even of Time.

Related

Article:

Kosinkski

- Between Good and Evil

Also

by Phillip Routh:

The

Sea Gull

Philip

Roth's Everyman

READER FEEDBACK

COMMENTS

user-submission@feedback.com

I think as the article says that he was someone who was so

egotistical that he tried to make people believe that he had

experienced what he wrote about. It was too fantastical. He

loved to be the center of attention. He was a poor gigafo

who married a rich woman to further his ambitions. I read

The Painted Bird in the late 1970s as an impressionable

teenager and was shocked that such a lewd novel was in our

high school library. Well I guess Jerzy was just another slick

operator out to make a buck.

Dalutsko@verizon.net

This Instagram world demands a level playing field of moral

equanimity - let he who is without sin cast the first stone.

Creativity is not bound to Political Correctness or to axiology

provided the voice presented is authentically moving: artists

regularly steal from one another. Kosinski was a self-made

individual who raised the bar for himself, and for us all.

drjknight177@gmail.com

I agree with Phillip Routh on the issue of whether Kosinski

wrote the books attributed to him. Yes, The Painted Bird

is fiction, not fact, but it is great fiction, and it

reflects the truth of man's inhumanity to his fellow man,

whether it is reflected in the Holocaust, the Armenian Genocide,

or any other of the atrocities committed in every generation

since the dawn of recorded history.

I had dinner with Jerzy Kosinski at Elaine's, the literary

hangout in NYC, in 1977, and the man's authenticity was as

clear as his tragic view of life. He was driven to suicide

by the insensitive attacks of heartless critics who failed

to appreciate that his dark vision was a genuine reflection

of his childhood experience of real atrocities that most of

us fortunately never see, and his greatness lies in his unique

ability to translate those experiences - whether they were

literal truth or products of his dark imagination - into great

art which transcends the boundaries between one man's experience

and our universal horror at the Hell that our species has

always been capable of creating.

His untimely death demands both our "sense of pity"

and our admiration for a man who had the courage to confront

his inner demons and the genius to translated them into timeless

truth, and whose best work will long outlive the cruel personal

attacks made upon him by far smaller men whose egos led them

to focus on his deficiencies as a human being instead of the

work for which he will be remembered far beyond his century

and ours. Joseph Knight, A.M., M.D.

user-submission@feedback.com

Shortly after Being There was published in 1970,

I gave my mother, a Polish Jew born eight years before Kosinski,

a copy with my enthusiastic review. After she read it she

told me it was okay but that she had already read it, years

before, in Polish. Polish readers noticed the similarity of

Being There to a popular Polish novel, too, and it

was noted in 1972 in a Polish publication. I had no way of

finding the book back then. Years later I read other similar

accusations. The Village Voice and others had not

yet accused him of having all his books ghost written, either.

That came in the 1980s. The accusations didn't surprise me

because I did not doubt for a minute that my mother had "already"

read the book in Polish. Without having read the Polish novel,

Routh refers to a plot summary and emphasizes the differences

between the two books. But my mother's certainty that she

had read the book years before in Polish tells me that plot

specifics aside, the general flavor of the two books was more

similar than different.

user-submission@feedback.com

I have read this article on the life of Jerzy Kosinski some

10 years after it was published by Phillip Routh and over

25 years since the untimely death of Jerzy Kosinski. Routh

gives a very balanced account and my sense is that it is fairly

accurate. I have no doubt that Kosinski's "focus"

the darker side of human nature (some commenting here like

to refer to as a payhology) stems from the very troubled times

he grew up surrounded by in Europe at that time. I tend to

much prefer positive, and much more myself optimistic

art myself - yet there is also a valuable lesson in looking

at the darker side of humanity that can teach us how not to

be. And we should all reflect on this possibly as well before

leveling all kinds of criticism Kosinski way. He was a profound

man (as anyone seeing him speaking and being interviewed would

attest to). Additionally what I find disturbing is the terrible

politization of his critics in wanting to de legitimize totally.

And that is not only an assault on truth - it is and was tragic

as well.

xperdunn@hotmail.com

Thanks for this info -- I read Painted Bird in my

youth -- it shocked me and kind of hit my idealism a blow

to the head. It wasn't til I tried to read Steps

that I felt a sick bias in the author -- that sick bias which

you rightly point out is today a staple of hollywood. And

I agree that nothing written in 1932 could be plagiarized

into Being There -- my favorite of his bitter creations.

Kosinski taught me that writers (and readers) can choose darker

or lighter paths of expression, but it is important to discern

between artistry and indulgence, for mental health reasons

if no other.

pennyd@dakotaprovisions.com

What you wrote here is enlightening for me. When I was in

high school, and later, majoring in English Lit. in college,

I had awareness of Mr. Kosinski's books. I never read them:

I glanced through one at the library, and when Being There

came out as a movie I was aware, and paid attention; a fellow

student at B.U. once described to me a disgusting sequence

of physical abuse in one of Kosinski's novels . . . I felt

two conflicting things: he's apparently an important writer,

I should read him; and 2) I don't want to read that, it sounds

awful -- do I have to tolerate, or "put myself through"

reading about horrific brutality? Reading about it in reviews

was bad enough. I made the decision to not read any Kosinski

novels, and now after reading your article here, I feel all

right with my decision. Life is short, and has enough challenges.

I don't have to put stuff into my head that is horrible and

I won't be able to get out, afterwards. (In my own writing

efforts, I try to bring -- Humour and Light . . . ) Thanks

for your article. (blue collar lit .BlogSpot.com)

jerzypawlusiewicz@wp.pl

I read Being There some forty years ago, when this

book was still illegal. Of course I know, The Career of

Nicodemus Dyzma. Everyone in Poland knows it.

Chance nearly became president of the United States, as Disma

- Polish Prime Minister. It is obvious to me that although

Kosinski's novel is not 100% plagiarism, however, many alarming

similarities between them are easily recognizable.

user-submission@feedback.com

I think your take on Kosinski is balanced and insightful.

There's an undeniable power to his writing, but it's the power

of sensationalism --violence and grotesqueness with no ability

at comprehension. D.H.Lawrence wrote of a Hemingway book:

"Everything happens, nothing matters." It's hard

to brush away the inhumanity of Kosinski's violence as not

mattering, but there's no sense of emotional comprehension

on the author's part: he's displaying his pathology. Still,

it's a performance that's hard to ignore.

martibohn@gmail.com

JK's work will outlive the scandals. Do we care who wrote

Shakespeare?

tom@tommallon.com

Interesting. I never understood his fall from the grace of

publishing houses, and never considered his work to be more

than fiction, possibly based on some horrid personal experiences.

I did liken his writings to the works of (which you site here).

I never questioned his darkness or that of anyone that had

lived in Europe during those days of madness. My friends and

I read his books and accepted, even enjoyed his surreal, angry

world. We were very young and Vietnam was raging. His work

just seemed to fit.

My view today is that he was an incredible wordsmith and

that his works were on a level considerably beyond just good.

The very consistency of his work was beyond what some considerably

bigger name authors were capable of. From a painter's perspective,

if you take the Renaissance to the 19th century, all these

artists' works were the products of studios. By comparison,

Kosinski had more involvement then most of those artists.

So, when the Village Voice scandal broke my friends

and I merely shrugged. Even the sharpest critics cannot not

question the originality of his vision, which I consider to

be any artist's obligation. Today, I still consider the books,

if not the author, to stand on their own and hope today's

publishers might think beyond themselves and reestablish this

body of work for future generations.

I never met the man, but am certain I would have been impressed

by the unique energy which he managed to instill into his

mindful creations. In the end, nothing else really matters

except that these fine works would not have emerged without

him.

jcorrigan5555@hotmail.com

Much is still being written of World War II, and probably

will be for some time. It's not just that this war surpassed

WW1 in 'shock and awe', but that a fundamental shift occurred

therein. It's hard to find another example of mob madness

and depersonalization that grew in Nazi Europe. Even though

Stalin murdered more people he didn't generate the cult of

personality and lust for terror that Hitler and his Nazi's

managed. Its often said that Hitler was insane, but this didn't

disqualify him from ruling the world. I'm sure some of what

happened then is unknown in memory. If Jerzy Kosinski conjures

these cruel events, weather real or imagined, a brave one

is he.

user-submission@feedback.com

Great article. Jerzy was a genius. And he was a profound genius.

This will ultimately be his legacy in his writing and his

life.

tazag@yahoo.com

This article brought tears to my eyes. I read The Painted

Bird as a high school sophomore. I was probably a little

too young for it.

user-submission@feedback.com

JK is a writer who was misunderstood by a majority of his

critics. After all, they did not grow up in the East. I did.

His novel Blind Date, for example, is a perfect journey

into a human mind transformation from kind to evil under a

soviet regime. It is evident that all his novels do display

this kind of mind trauma/transformation. No wonder his talent

was unappreciated. In general western people do not want to

believe that brutality and communism go hand in hand.

user-submission@feedback.com

Thank you for the thoughtful analysis. My own assessment is

along similar lines. There is a stylistic similarity to his

novels - the flat affect, the everydayness of horror, the

sexual liberation that does not bring people together, the

nihilism that penetrates all relationships etc. Yet there

is a depthlessness to his work, especially Steps,

that gives the sense that he was already dead in some sense

before his physical death.

pszemanczky@aol.com

I wish I could have interviewed him for Project Shining City

as I'm sure his politics would have been drawn toward his

incredible-logical conclusions. His 3 great literary successes

outclimb his fall by 10 light-years - and I'm sure he'll be

rediscovered one day by some producer urging his wife to create

The Painted Bird for the rich panavision of his vision

in all its sensual lust and gore as only Hollywood dreams.

His own biographical life is truly of the 21st Century 'stuffofdreams'

and bears being told in some iconic myth, don't you think?

mike.baniasadi@gmail.com

I have read all his Novels. I think Being There was

the first novel I finished and it led me to appreciate fiction.

I found his biography (Not the autobiography) to be very interesting.

I always thought that Hollywood should make a movie about

his life.

user-submission@feedback.com

This is a very interesting article. I am not a reader of Jerzy

Kosinski, his story lines would have been a bit too strong

for my taste although I did see the movie Being There.

I came to this article while reading about Elle Wiesel and

became interested in Jerzy Kosinski. Thank you for such a

well balanced article.

user-submission@feedback.com

What a paternalistic bunch of bull. Who is this guy Phillip

Routh anyway?

user-submission@feedback.com

The Painted Bird controversy is absolutely ridiculous.

Of course it's fiction! I think you would have to be one of

those backwards characters from the book to actually believe

it was a true account of a boy's experience: the lad always

miraculously escaping at the last minute, a farmer gouging

out eyes from an admirer of his wife -- this is pure fiction.

Even if Kosinski did portray it as real experiences (and he

didn't, it was his idiot publisher to sell copy), you would

have to be a total fool to believe him. Anyone who felt misled

by this wonderful novel deserves to be duped. The book represents

great writing and if Kosinski didn't write his books (which

I believe he did) then let the ghost writer(s) come forward.

So far 20 years after JK's death we have nothing but some

implausible poet somewhere making unauthenticated claims.

It's time to lay off the "we were misled by JK bandwagon,"

Let the guy rest in peace and enjoy HIS writing.

jiminireland@gmail.com

I've only read and reread Cockpit, and found it a

compelling page turner, carefully structured to keep the reader

wanting more. Thanks for an interesting artice on JK as I

was curious to know what type of author would create such

works. There is definite evidence that he condensed a lot

to avoid it becoming boring, which it never was. I admire

Cockpit for it's edge and will no doubt read it again.

Regardless of his faults he gave a reader a good story.

jack_son@net.hr

I think that Cockpit is his best novel.

kuperjack@yahoo.ca

I was his friend and after his demise I made a the film Who

was Jerzy Kosinski?

Yet so many years later the question still haunts me.

Jack Kuper

romahoward@gmail.com

Being There and the subsequent movie were excellent.

Excellent in that the humor was truly funny because, in an

absurd way, it is all too frequently the way people achieve

fame and fortune. Human effort may not play a major part of

anyone's rise to the top. In fact, real talent and ability

may be an obstacle to achievement. However, I am perplexed;

how can anyone who wrote such an insightful and humorous book

take their own life? Thanks, Ron Howard