PHOTOGRAPHY IN TRANSITION

by

ALEX WATERHOUSE-HAYWARD

______________

Get

modern or get fucked.

In 1979, the Modernettes,

my favourite Vancouver punk band, had that as their motto. They

spray painted our back alleys with it. I think of it every morning

when I wake up to face the uncertainty of being a photographer

in our 21st century world where photographs are no longer taken

but captured. It is a world with cameras that have something

called face recognition technology.

We

no longer have Oldsmobiles. Who drives Buicks and Plymouths?

My photo world is changing as rapidly. There are no more Minolta

SLR cameras, Agfa is gone, and the great yellow box’s

(Kodak) presence is so diminished that Ektachrome might soon

be a fading memory. Photo labs in Vancouver are dropping like

bodies in Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None.

The uncertainty in my world of the freelancer is compounded

by the rise of micro stock agencies that sell photographers'

images for cents. And there is confusion, too. Consider the

logic of manufacturing state-of-the-art digital cameras while

calling yourself the Fuji Film Company.

This

change goes deeper, paradoxically, as more images end up on

computer monitors. Nobody would deny that a monitor image has

only two dimensions. The so called “rules” of composition

in photography were created to compensate for the loss of that

third dimension: depth. Diagonal lines in photos create a sense

of movement. But for me, while an image on a monitor has those

obvious two dimensions, a hard copy photograph (silver gelatin

print, inkjet, light jet print, giclée, etc) has a third:

thickness, which provides for heft and feel. Photographs have

two sides. If a particular photo happens to be an expensive

vintage print, it will be signed and dated by the photographer

on the back.

Rising

in popularity are frames that are able to display digital images

as well as scroll from one image to another. Will there soon

emerge a generation of photographers who will have lost the

ability to discern subtleties like shadow detail in the blacks?

This comes from looking at an image for more than a few seconds.

They now want images that are not static, with colours that

are unreal or sharply contrasted -- code for zip and punch.

Technicolor is back.

Rising

in popularity are frames that are able to display digital images

as well as scroll from one image to another. Will there soon

emerge a generation of photographers who will have lost the

ability to discern subtleties like shadow detail in the blacks?

This comes from looking at an image for more than a few seconds.

They now want images that are not static, with colours that

are unreal or sharply contrasted -- code for zip and punch.

Technicolor is back.

In

the web-medium of Arts & Opinion, I cannot show

examples of the wonders of light jet prints (digital files on

laser heads are projected on to photographic paper) or the look

of a well printed giclée (artspeak for a high end commercial

inkjet print on art paper). These prints can show a delicate

transition of colour that is lost on a monitor.

I have

had senseless arguments about film versus digital with photographers

on on-line photo forums. They are no different from religious

or political ones. None of the participants will give ground

as debate invariably degenerates into shouting and insults.

But recently I saw the light. One photographer on the digital

end of one day’s argument noted that the scans of my original

transparencies (large slides) were poor imitations of the real

thing.

I thought

about the “real thing.” I got back to him saying

that in reference to my slides I could burn them, twist them,

project them, print them and even ignore them in a shoe box.

And if I wanted to I could even chew on them. I then asked him,

“Where is your original? Is it a series of 1s and 0s inside

a memory card? Can you touch and chew those 1s and 0s?”

But

my victory, when he could not get back at me, seemed hollow.

If I have not adopted the digital camera, it partly due to the

expense of the transfer. To switch from my medium format camera

to digital I would have to buy a digital scanning back. Which

means I would have to invest around $50,000 in order to retain

the quality of detail I now enjoy.

Photography

is in a hard-to-predict transition. Those who shoot digital

are out to prove their digital cameras can mimic film. They

print large images and ask you to guess if they are digital

or photographic prints. This is senseless. What would you think

of a person driving a horseless carriage that could deposit

stuff on the street every few blocks that looked like horse

droppings? But it’s wrong to think that digital photographers

must look forward, toward the future, for an indication of where

they are going, while leaving us, who shoot film, in our past.

The

word ‘tool’ is used a lot in these arguments. You

placate your opponent by saying that a camera is a tool and

you use whatever tools fits or suits your needs. Which is why

a hammer suggests hammering nails or removing them. Or if you

wrap a hammer with cloth you can bang a loose chair joint. A

screwdriver, besides its conventional uses, could be used for

digging seed holes in the ground. It is the very nature of the

tool that suggests the end use.

The

word ‘tool’ is used a lot in these arguments. You

placate your opponent by saying that a camera is a tool and

you use whatever tools fits or suits your needs. Which is why

a hammer suggests hammering nails or removing them. Or if you

wrap a hammer with cloth you can bang a loose chair joint. A

screwdriver, besides its conventional uses, could be used for

digging seed holes in the ground. It is the very nature of the

tool that suggests the end use.

And

it was via this hammer and screwdriver comparison that I discovered

my personal solution for photography in today’s transition.

It consists in remembering that film occupies physical space.

But I also remember that film can be digitized and that this

process brings into the mix the best of both those worlds. I

would hope that those shooting digital will remember photography’s

roots when they are in search of a creative solution.

To

share a telling example with you, a year ago I was assigned

to photograph Canadian baritone Brett Polegato. He was in Vancouver

to sing the Vancouver Opera’s production of Mozart’s

Don Giovanni. I wanted to tell the story of how this womanizer

ends burning in hell. My solution was to take nine pictures

using a ring flash. I then picked one of the negatives and lit

it with a match. It cracked beautifully! I then scanned the

negative for the end result. I am not sure that I would have

come across this elegant solution had I been thinking digitally.

On another job, I had to illustrate a cast of actors who were

in a play about oriental heritage called The Banana Boys.

I photographed them, again with my ring flash. I scanned a banana

on my flatbed and added it as a frame.

Thinking

digital, I have come to love the look of the lowly Polaroid.

It is beautiful when scanned. I scan b+w Polaroids as colour

so my scanner injects a pleasant cool blue tone. Here you see

Canadian modern dancer and choreographer, Noam Gagnon, who is

one half of the famous Holy Body Tattoo. I sometimes scan the

Polaroid peels, particularly the colour ones.

Here

is an example of Canadian violinist Corey Cerovsek.

I haven’t

abandoned completely printing my own conventional b+w prints.

Here you see one of fencing Master Bac Tau and his pupil scanned

and modified. With a scanner and Photoshop I am able to find

colours that exceed the possibilities of conventional photo

toners.

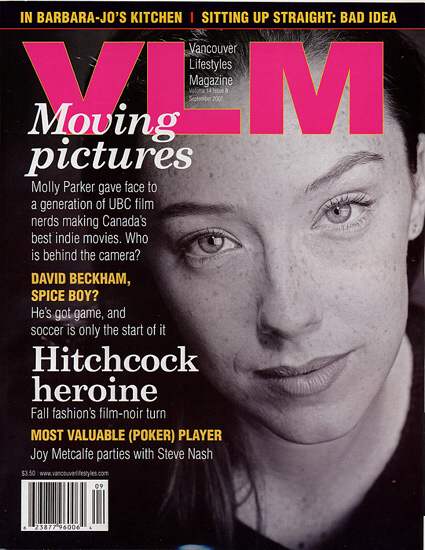

As

a magazine photographer, I have discovered that some of the

better magazines in Canada use digital offset printing. This

method opens all kinds of possibilities for detail and sharpness

that at one time was impossible. Here is a recent cover made

from my b+w negative of Canadian actress Molly Parker. The negative

was drum scanned. I would have been hard pressed to get as good

a print in my darkroom.

And

for my personal stuff I like to work with this hybrid system

of film/digital. "Yuliya Tied Up" is a scanned Polaroid.

"Tarren’s

Bum" is the result of treating a b+w negative as a colour

negative. I can get realistic skin tones or loud fiery ones.

“What

kind of photographer are you?” I am often asked. Of late

I like to reply, “I’m like a Toyota Prius.”

For

more of Alex's photography, visit his website at:

www.alexwaterhousehayward.com