FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION

with

ERICA POMERANCE

Erica

Pomerance is a documentary filmmaker from Montréal, Québec.

Her award-winning film Dabla!Excision was produced

by Monique Simard at Productions Virage for Canal Vie Television.

For more information about the film, visit www.dabla-excision.com

or contact the distributor Films en Vue at info@filmsenvue.ca

NOTE: THIS INTERVIEW CONTAINS DISTURBING MATERIAL AND

SEXUALLY EXPLICIT GRAPHICS

_____________________

A &

O: You would concede there is a difference if I report to you

that my finger has been removed as opposed to mutilated?

ERICA

POMERANCE: Of course, a finger may have to be amputated for

health reasons, whereas a mutilated finger implies at best an

accident or injury. So the two terms have different implications.

A &

O: In most African countries where female excision is practised,

the young women don’t think of themselves as having their

vaginas mutilated, do they?

ERICA

POMERANCE: In traditional African society, it is not the widely

prevalent concept. In fact, many girls look forward to the event

as an initiation, an essential rite marking their entry into

adulthood, much like the young girls anticipate the Christian

confirmation ceremony. However I would like to specify that

FGM is not religious in origin.

A &

O: So if Africa doesn’t regard female excision or clitoridectomy

as a mutilation, what right does the West have to impose this

pejorative term on their practice, and beyond that, what right

does the West have to interfere in African cultural practices?

ERICA

POMERANCE: First of all, the West is not imposing the term FGM

on anyone. A movement exists across Africa comprised of women

and a growing number of men who object to the custom because

it violates the rights of women and children and has negative

physiological and psychological ramifications. The Inter-African

Committee against Harmful Traditional Practices (IAC) founded

in 1984, has national committees in 26 African nations, and

at their insistence, the United Nations adopted the term ‘female

genital mutilation’ to describe specific ritual removal

of all or part of women’s external genital organs.

ERICA

POMERANCE: First of all, the West is not imposing the term FGM

on anyone. A movement exists across Africa comprised of women

and a growing number of men who object to the custom because

it violates the rights of women and children and has negative

physiological and psychological ramifications. The Inter-African

Committee against Harmful Traditional Practices (IAC) founded

in 1984, has national committees in 26 African nations, and

at their insistence, the United Nations adopted the term ‘female

genital mutilation’ to describe specific ritual removal

of all or part of women’s external genital organs.  The

movement to stop FGM actually had its origins in Africa, albeit

somewhat timidly. The West has embraced and sponsors the movement,

especially in regard to efforts to educate the population on

the hazards of FGM.

The

movement to stop FGM actually had its origins in Africa, albeit

somewhat timidly. The West has embraced and sponsors the movement,

especially in regard to efforts to educate the population on

the hazards of FGM.

A &

O: How did you get interested in this cause?

ERICA

POMERANCE: I first heard about FGM in the early 1980s, shortly

after it had been denounced publicly by Western feminists such

as Kate Millet at the 1976 UN International Women’s Conference

in Nairobi. A debate subsequently arose in feminist circles

around cultural appropriation of the question. African women

were feeling the brunt of what seemed to be an accusation by

Western feminists, who portrayed them as either complicit in

the act or as its helpless victims. Put on the defensive, African

woman forcibly entered the FGM battlefield. They expressed the

position that since they were the ones affected, FGM was an

African problem that required an African solution.

A decade

later, on my first trip to Africa, to research the role of primary

healthcare givers, I encountered evidence that a lively debate

around the excision controversy was emerging across the continent.

It seemed to be a good subject for a film. It took me five years

of research and reflection to get my documentary project together.

And another five years to shoot, finance, and release the film,

thanks to producer Monique Simard and the team at Virage Productions.

I spent several winters in fancophone West Africa, meeting people,

filming events and taking the pulse of the anti-FGM movement.

It was quite a learning experience, one that has radically changed

my life and the way I think about gender politics.

A &

O: What is the difference between clitoridectomy and infibulation?

ERICA

POMERANCE: Clitoridectomy involves removal of the clitoris,

whereas excision is removal of the clitoris and minor (inner)

labia. Infibulation, the most extreme form of FGM, entails removal

of the clitoris, the major and minor labia, after which the

vagina is sewn up, leaving only a small orifice for urination

and menstruation. Infibulation is practised primarily in East

Africa, although it occurs among specific ethnic groups such

as the Fulani in parts of West Africa.

A &

O: Would anti-FGM activists feel more comfortable with FGM if

it were practised under sterile medical conditions in hospitals

and clinics?

ERICA

POMERANCE: A prevalent fear in the anti-FGM community is that

medicalization of FGM would be used by its proponents to justify

a practice that deprives women not only of their sexuality,

but of free choice and control over their own bodies. For this

reason, most anti-FGM activists support a position of zero tolerance.

Medical excision has its health risks as well, since the Mercurochrome

used to cauterize the surgical wound often causes scarring and

seals the vagina.

A &

O: If I understand correctly, men just didn't invent this custom

out of the blue. They introduced the custom of clitoridectomy

to control the sexuality of their women.

ERICA

POMERANCE: No one really knows the origins of excision. It undoubtedly

existed in pre-Pharaonic Egypt. It perhaps originated during

the Neolithic era or around the time when agrarian society developed

animal husbandry and metallurgy was introduced. After men realized

the role they played in fertility, they began to tame and exert

sexual control over women for breeding purposes. A man had to

ascertain that the children his women were carrying were his,

and not someone else’s. Some anthropologists presume that,

in fact, FGM was instituted in reaction to men’s fear

of women’s sexuality. In the context of the times and

evolution of the species, excision seemed a logical and effective

control over fertility, female promiscuity and paternity.

Men

feared women’s promiscuity most probably because they

were projecting their own patterns of behaviour and sexual desire

on women. Historically, it has generally been men who are promiscuous.

Numerous traditional societies around the planet are polygamous,

whereas few cultures have allowed women more than one male partner.

This state of affairs is certainly due in part to the fact that

women are biologically conditioned to monogamy (or at least

serial monogamy) since they are preoccupied by the full-time

tasks of bearing, feeding and nurturing young children and have

little leisure to develop a complex system of multiple sexual

and martial partnerships, particularly considering that the

uterus cannot bear the fruit of more than one pregnancy at a

time.

From

a strictly biological point of view, men will inseminate as

many women as they can handle in order to ensure their genetic

survival. From earliest history, men always fought -- sometimes

to the death -- over the possession of women; the more women

they control and protect, the greater their power. Fearing both

the sexual prowess of woman and the rivalry of younger, more

virile males, men probably introduced the custom of clitoridectomy

as a projection of their own libido, in order to limit a woman’s

capacity for achieving pleasure in orgasm. In this way, the

children she bore would most likely be begat out of duty to

her master and not through pursuit of sexual desire. A man could

easily repudiate a wife and abandon a child and any infant suspected

of being another man’s progeny. Such a woman, rejected,

was separated from her legitimate offspring and afforded no

further protection by her kin against rape, thus exposing her

to enslavement by a rival tribe. We shouldn’t forget that

in cultures where female excision is practised, a woman with

intact sexual organs is regarded as unmarriageable, leaving

her, for all intents and purposes, rejected by the community

and by her cultural group.

But

let’s be honest. Not only in Africa, but around the world,

men have traditionally feared and resented women’s power,

in particular, their sexuality. The clitoris is four times more

sensitive than the penis. Women’s orgasms, measured by

contractions, last longer than men’s, can be multiple,

and don’t diminish with age. FGM is just one response

to men’s collective resentment or fear of women’s

sexuality and reproductive fertility. In pre- Biblical times

men worshipped the Goddess of Fertility in many shapes and forms,

until the revealed religions discovered a supreme male God who

robbed the Goddess of her power. But that was not unique to

pagan, animist societies. In our supposedly enlightened West,

we only have to look at how the Church has tried to control

and stigmatize female sexuality. In the century following the

invention of the Guttenberg press and mass production of books

that empowered and enlightened the middle and upper classes

of society, the Catholic Inquisition burned more than 100,000

women at the stake as witches.

Reduced

to its lowest common historical denominator, we find ourselves

faced with the overwhelming fact that men have never been comfortable

with women’s sexuality. And women have been eager to comply,

adopting self-mutilating behaviour with the aim to please and

seduce men, whether it be through excision, the chastity belt,

the corset, esthetic surgery or the crash diet.

A

& O: Walk us through a clitoridectomy.

ERICA

POMERANCE: I have not actually witnessed one myself, except

on film. I do show a brief archival excerpt of an excision in

my recent documentary film Dabla! Excision. But this

is not the main purpose of my film, which examines many of the

sociological and medical aspects of FGM, and the role of African

woman in the movement to stop the practice

In

the opening scene of my film, shot in rural Guinea, we see a

typical village ceremony involving a group of girls between

the ages 3 and 6, who are brought together in a clearing. As

adult women clap and sing songs to encourage bravery and courage,

one by one the girls are led by a paternal aunt to a grass hut

in the forest where the procedure takes place.

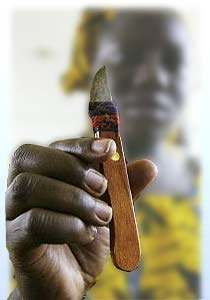

The

mortified child lies down on her back, her assistants hold the

girls legs open, while the female circumciser takes out a sharp

instrument (knife, razor blade or shard of glass) and removes

the clitoris. The girl’s cries can be heard by the others

waiting their turn outside. A mud or herb salve is then applied

to stop the bleeding.

The

circumcised children hobble single file to the centre of the

clearing where they are seated on a mat. The village women dance

around them, singing ceremonial songs that honour their entry

into womanhood. The girls are then sequestered for two weeks

to one month while they heal, but the operation often scars

them for life. We should note that in most societies, this custom,

originally introduced by men for their own benefit, is performed

exclusively by women and takes place in the company of women.

Women thus accept to serve as proxies for men, and the female

circumciser occupies a position of status in the community.

A &

O: If men refuse to marry women who are not excised, shouldn’t

your crusade be directed at the men behind this barbaric custom?

ERICA

POMERANCE: Most anti-FGM campaigns in Africa target the various

segments of the population: men and women, students, religious

and political leaders, and female circumcisers themselves. The

information is tailored to each specific target group. Wherever

funding is made available, trained African women and men knowledgeable

about ethnic practices in the targeted region hold a series

of in-depth information sessions and frank discussions in the

villages. When possible, they use support material such as films,

photos, leaflets, diagrams (la boîte aux images), a three-dimensional

model of a female torso with removable genital parts. After

harmful physiological, psychological and social aspects of the

custom are clearly explained and elucidated, people begin to

question the necessity of FGM. However, you can’t expect

to change ancestral cultural beliefs overnight. The following

such myths still prevail: left intact, the clitoris can grow

down to the feet (another projection of women's penis envy?);

a woman with a clitoris is impure and cannot prepare a man’s

food; if the baby’s head touches the clitoris during childbirth,

the infant will be deformed for life; a woman with a clitoris

wears her sexuality for all to see.

The

growing opposition to FGM has also sparked a backlash among

certain Islamic groups and as a result, more female circumcisions

are being performed in infancy or in early childhood. In the

cities, FGM is now performed by medical personnel in certain

clinics. Laws are difficult to enact. In countries where anti-FGM

legislation already exists, it is difficult to enforce, since

extended family members tend to protect each other and female

circumcisions continue to be held in secret. Nonetheless, a

small but growing minority of men and women are coming to view

the custom as unacceptable. Naturally, in larger cities, where

the educated middle class has more access to information via

the media, liberal attitudes tend to circulate more freely about

women’s rights and sexuality in general.

A &

O: To what extent does clitoridectomy deprive a woman of her

sexuality?

ERICA

POMERANCE: Obviously, clitoral orgasm is no longer possible.

But that is not the primary criterion for sexual satisfaction

in many traditional African societies. We should remember that

only since the recent sexual revolution, has the West become

very orgasm-oriented. We are conditioned to believe that orgasm

and sexual fulfilment are one and the same. For many mutilated

women, the sexual act is a marital duty performed without expectations

beyond that of successful pregnancy and childbirth. In Africa,

a woman’s satisfaction may be related to her sense of

security and that of her family, whether her husband cares and

provides for her economically, and her status in the community.

I personally think there is much we can learn from this.

A &

O: Talk to us about the health hazards involved.

ERICA

POMERANCE: Female circumcision often results in complications

to reproductive health. For the majority of African women, this

constitutes a more urgent preoccupation than the fact that women

do not attain orgasm. Sexually mutilated women suffer from a

number of disorders including infertility, prolapsed uterus,

incontinence caused by vaginal fistula. After infibulation,

the vaginal orifice is sewn up, and later on a woman usually

requires surgery in order to have intercourse and give birth.

Many women suffer permanent damage to their reproductive systems.

These complications are discussed in detail by gynecologists

in my film. The film web site contains graphic photos of certain

medical disorders.

A&

O: Given the widespread incidence of FGM in many African cultures,

is it fair to accuse men of introducing the custom of female

circumcision with the purpose of controlling women’s sexuality,

while relieving themselves of the responsibility of satisfying

their multiple partners sexually? If a woman has been physically

desexualized, is the man off the hook?

ERICA

POMERANCE: Are men to be blamed for the way humanity has evolved?

It’s a tricky question. Whether it is fair or not to accuse

men of instituting FGM is just about as difficult as asking

if it is fair to accuse men of war and patriarchy. Humanity

has evolved in a very sexist manner, but who is to blame? This

is an unfortunate state of affairs, because now women have a

huge task trying to gain their most basic rights, specifically

in those traditional cultures that are still actively suppressing

women’s rights, often as a backlash to the extreme liberalism

(which some consider decadence) of the industrialized West.

No doubt we should have fought back before the patriarchy was

institutionalized. But that’s a long time ago, and perhaps

we didn’t have the means to fight back collectively, or

even the insight to recognize that we were losing what we now

consider basic human rights. As to whether or not a man is off

the hook when a woman can’t achieve orgasm, I doubt it.

In the West many men suffer because their wives are frigid even

though they are sexually intact. Look at the number of men taking

Viagra in societies where women are not sexually mutilated:

the erectile problem continues to plague them, with or without

women’s capacity to have orgasm. Of course, in Africa

and in other cultures where polygamy is the norm, having up

to four legitimate wives to service must be exhausting after

a certain age…

A &

O: In making your film,

Dabla!Excision, you spoke with several

African women who now live in Canada. Given the importance of

sexuality in Western society, how does an excised or infibulated

woman negotiate her sexuality in our liberated culture?

ERICA

POMERANCE: Most African woman in Québec with whom I have

discussed FGM are fed up with the focus of attention given to

the problem by the media here. They generally feel the issue

has been sensationalized to such an extent that they feel they

are being undressed when people look at them. It is a degrading

experience to feel one is considered purely in terms of “is

she or is she not sexually mutilated?” One woman I know

reacted this way when I told her I was making a film about African

women and FGM. She said that she hoped I wouldn’t be asking

“the question”. For her, being asked whether or

not she has been circumcised is as humiliating as asking a white

woman whether she has vaginal or clitoral orgasms. She feels

the question is an invasion of her privacy and shows a lack

of respect, since it defines her identity as an African woman

through the condition of her genital organs.

Many

women have left Africa in the hope of turning the page, and

would prefer to leave the FGM issue behind them. That is why

many African women in the West refuse requests to tell their

excision story. The media has generally focussed on the more

sensational aspects of FGM, whereas it might be more pertinent

to highlight the efforts underway to stop the practice both

in Africa and clandestinely within our own borders. There are

also services Canada can provide to help mutilated women, by

creating increased sensitivity about FGM- related gynecological

problems within our medical system, and by more readily offering

asylum to women and children fleeing the imposition of FGM in

their country of origin.

Part

I of FGM appeared in

Vol. 5, No. 2.

Related

articles:

Prostitution:

Gender-based Income Redistribution with Honour and Dignity

All

Abored the Porn Express

Sex

Traders in the Material World

21st

Century Sex

Pop

Divas, Pantydom and 3-Chord Ditties

The

Triumph of the Pornographic Imagination

COMMENTS

user-submission@feedback.com

People Muslims and the rest wake up! Those who preform female

genital mutilation (FGM) on children should be brutally killed;

it's a crime to do this kind of things to children; it's disgusting,

sick and totally abnormal. Each one who has thoughts even

to take his/her daughter for FGM must to seek treatment. It's

so bloody abnormal; it's the same as cutting fingers or toes.

The world needs to speak up and punish all the bastards abusing

innocent children making them to suffer and feel pain and

trauma for the rest of their lives. It's not a mother, but

a bitch who gives her own daughter for FGM. Those people must

be punished.

If

you are an institution that has included this article in

your curriculum or reading list, we ask for your support.