from the blogosphere

THIS JUST IN: HAITIANS ARE DIGNIFIED

by

DAVID LIEBER

____________

David

Lieber is a communications writer, translator, catophile and

occasional blogger.

There's

been a lot of talk on TV and in the press about how “dignified"

Haitians have been in the aftermath of their recent catastrophe.

There's

been a lot of talk on TV and in the press about how “dignified"

Haitians have been in the aftermath of their recent catastrophe.

But my dictionary defines dignity as "the state or quality

of being worthy of honour or respect."

So exactly how did those journalists view Haitians before

the earthquake? Did they imagine that only some thin membrane

of social order prevented the population from reverting to

cannibalism?

And what's all this about "shoddy construction"

and "building codes?" Were they really so unaware

of the trade-offs likely when the average annual income is

$1300 -- for food, clothing and earthquake-proof construction?

And why would anyone assume dignity to be in short supply

in the poorest country in the Western hemisphere? Unless totally

absent -- which it often is, conspicuously, in the developed

world -- dignity should be correspondingly more plentiful

in Haiti, under the circumstances. Poverty, tragedy and dignity

have worked together very well, every day, throughout the

Third World for several hundred years.

That's conjecture, of course, since I've never been confined

to such circumstances. But I imagine I'd find the dignity

necessary to endure them -- unless I’m just taking my

dignity for granted, like those journalists.

I

doubt Haitians are any more remarkably dignified today than

they were before the earthquake. And I'm certain they're no

less so than when, in 1791, they stood up to their masters

and said, “Enough of this! We cleared the land, we planted

the sugar, we tended it, we cut it down, we carried it to

your ships and made you wealthy. It's we who've made you rich

but we won’t be owned by anyone anymore. This land belongs

to us from now on, not you. Get out!”

In

fact, it would be more logical to assume Haitians’ dignity,

having successfully risen from servitude to victoriously repel

the European powers who had enslaved them, and to whom they

actually paid restitution -- as if guilty of some wrongdoing

-- with cash they couldn't afford over a period of 150 years.

In

fact, it would be more logical to assume Haitians’ dignity,

having successfully risen from servitude to victoriously repel

the European powers who had enslaved them, and to whom they

actually paid restitution -- as if guilty of some wrongdoing

-- with cash they couldn't afford over a period of 150 years.

Equally telling about the Haitian character, in my opinion,

is the dignity they naturally accord others. English-speaking

people regularly mispronounce the name of the country ‘HAY-tee.’

But the Haitian Creole word is spelled ‘Ayiti,’

which has three syllables, not two. And that word, itself,

comes from the original Arawak Indians’ name for the

island that was once theirs alone. It simply means ‘tall

mountains’ or ‘land of tall mountains.’

Ha-i-ti.

I find that significant. Very few Arawak Indians would have

been left by the time Haiti became the first independent country

in the New World, so they could hardly have been in a position

to insist what the name of the new country would be. But by

choosing that name, the former slaves chose to dignify the

memory of the original inhabitants of the island who'd been

decimated, like so many of their own, and by the same colonizers.

I

know less about Haiti and the details of its current situation

than the breathless journalists of CNN who've now officially

pronounced Haitians to be "dignified" in their suffering.

But what they were telling us, had they thought about it,

should have been, “Haitians have remained dignified

in their suffering.”

I

know less about Haiti and the details of its current situation

than the breathless journalists of CNN who've now officially

pronounced Haitians to be "dignified" in their suffering.

But what they were telling us, had they thought about it,

should have been, “Haitians have remained dignified

in their suffering.”

Not that I’m an authority, but I've been to Haiti, too.

I have my own anecdotal experience of the place and was an

admirer of Haitians, their popular and folk music, their painting

and some of its literature for a long time before I finally

visited.

That’s why, in 1996, I bought myself a ticket to Port-au-Prince.

The brief two weeks I spent in there, mostly in Jacmel (near

what became the epicenter of the quake) were among the most

memorable of my life; a voyage into the history and personality

of the marvelous -- and very dignified -- inhabitants of the

Land of Tall Mountains.

Which brings me back to what irks me so much about the word

‘dignity’ as applied to Haitians in their misery.

The following took place on my very last day in Port-au-Prince:

I’d been taking pictures, throughout my visit, with

an unfamiliar camera that eventually became my own. I was

killing time before catching my flight back to Montreal, drinking

a beer on the main thoroughfare, the Delmas, in an open-air

bar, observing the passing crowds through a powerful telephoto

lens.

Across the street was a huge pile of garbage, as there was

on every corner along the stretch. But at the top of the pile,

I saw someone moving. I pulled focus. It was an elderly man,

shirtless, standing waist-deep in the filth, his bony back

to me and his arms immersed to the elbows, searching, I assumed,

for what might be useful or edible.

But then he slowly turned to reveal his face. It was then

that I could see the pupils of his eyes were completely white

and that he was blind. Then, just inches from where he was

groping, I saw a dead dog. A dirty, dead white dog.

I had the picture framed, in focus and properly exposed --

or so I prefer to remember. But I couldn't press the shutter.

I concluded at the time -- perhaps explainable by everything

beautifully bizarre I'd seen during the previous two weeks

-- that if I were to take that picture, I'd be taking away

whatever remained of the blind man’s dignity, even though

he'd never have known it had been stolen by me and my camera.

Because for all I knew, the blind man may have been having

a relatively good day. It was not for me, or anyone who might

have seen the photograph subsequently, to judge how much dignity

the man possessed or deserved to be accorded. And at that

moment, he was undoubtedly worthy of my honour and respect,

despite what the photograph would have suggested.

That's

why I decided to keep the image in my mind rather than on

film where it would have been arbitrarily interpreted by others,

although I’m not certain I would have done the same

today, under those circumstances.

That's

why I decided to keep the image in my mind rather than on

film where it would have been arbitrarily interpreted by others,

although I’m not certain I would have done the same

today, under those circumstances.

Regardless. Although I’ve literally shouted for joy

whenever I’ve seen images of survivors pulled from the

rubble of Port-au-Prince, and although I'm happy that the

world appears to have genuinely rallied to their cause, with

everything else I've seen and heard about Haitians' "dignity

in suffering" these last few weeks, I'm happier still

that I turned my camera away that day in 1996.

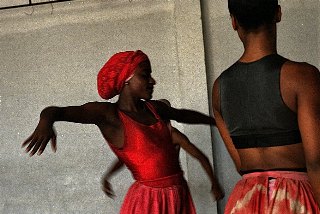

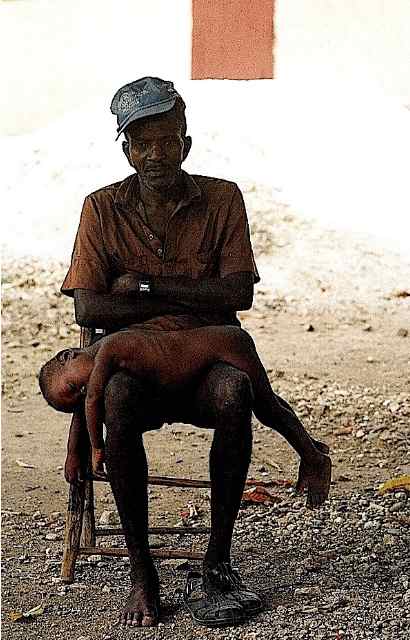

About the photographs: They were taken of Haitians in Jacmel

or else in Guantanamo, Cuba, which has a sizable Haitian refugee

population. The woman in the top photo was Clarita, now deceased,

who founded the Tumba Francesca dance school in that city.

The photo of the boy sleeping in his father's lap was taken

in Jacmel. It has shocked some people, but the boy was just

taking a nap and not nearly as thin as he appears in the picture.

Photos

© David Lieber

Related

articles:

Age

of Darkness (India)

Nubian Exodus

At Play in the Garbage Fields of the Lord