Sylvain

Richard is a film critic at Arts & Opinion. He

gave Beneath the Rooftops of Paris (Sous les toits de

Paris), which played at the 2008

Cinemania Film Festival,

3.1 out of 4 stars. For the rest of his ratings, click

HERE.

Sylvain

Richard is a film critic at Arts & Opinion. He

gave Beneath the Rooftops of Paris (Sous les toits de

Paris), which played at the 2008

Cinemania Film Festival,

3.1 out of 4 stars. For the rest of his ratings, click

HERE.

It's

a lesser known but poignant early work from the sculptor-architect,

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), to whom the great city of

Rome is indebted for much of its historic content and character.

The marble statue is entitled Aeneas Carrying Anchise.

It's

a lesser known but poignant early work from the sculptor-architect,

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), to whom the great city of

Rome is indebted for much of its historic content and character.

The marble statue is entitled Aeneas Carrying Anchise.

The

face of the helpless Anchise, who is being shouldered to safety

by Aeneas, so concentrates the fears and frailties of old

age, it’s tempting to conclude that Hiner Saleem’s

latest film, Beneath the Rooftops of Paris (Sous

les toits de Paris), was directly inspired by the Bernini

work. But whatever the sources of Saleem’s inspired

script and direction, they leave no doubt that he has meaningfully

confronted the existential question of aging and mortality,

and leaves the viewer with helpful road map of the pitfalls

and uncertainties the journey entails. As such, Rooftops

is an unapologetically melancholic film infused with grace

and grandeur, whose small sets and deliciously parsimonious

dialogue allow precious glimpses of how aging is likely to

affect, and how one might better serve others already on  that

much traveled and worn road.

that

much traveled and worn road.

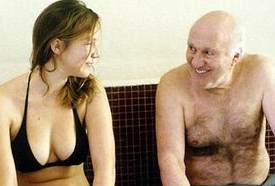

The

quietly told story of Rooftops revolves around Marcel,

played by owl-wise Michel Piccoli, now in his 80s, who is

living in a tiny working class flat in Paris. Marcel’s

two pleasures in life are cooling off in a nearby pool with

a friend, Amar, and his encounters with the waitress, Therese,

with whom whatever small affections in life are available,

they share together in fleeting moments under the constant

menace of solitude and unease, as the old one takes stock

of his decline. Observing the ailing Marcel surrender to Therese’s

smallest caress, we are introduced to a body that has been

coaxed to make peace with its infirmities and slow response

in order to assure its basic needs. To that end, master thespian

Michel Piccoli’s furrowed face is like an illuminated

manuscript that teaches us  how

to face our fears and seize the moment in all its diminished

plenitude.

how

to face our fears and seize the moment in all its diminished

plenitude.

The

four seasons provide the film with both its architecture and

symbolism; they are understated presences that prefigure Marcel’s

gradual decline, his initial refusal of age and its portent

symptoms, and his desire to escape into whatever pleasures

can be had, which includes the company of a young homeless

woman who enters and then leaves his life like a short season

come and gone, but who is a more meaningful presence than

his absentee son, emblematic of the me-generation and its

fatuous self-absorption.

The

film owes its moods to its meticulously drawn small sets –

mainly Marcel’s rooms -- that seem to fold in upon themselves

in contrast to the larger outside world that is growing more

and more inaccessible; what is beyond the reach of the body

is left to the devices of memory and nostalgia.

If

great directing is invisible, like a great writer is hardly

more than a ghostly presence in his work, Sameer, whose early

films were Dol and Kilometre Zero, reveals

consummate skills in involving us in Marcel’s pains

and small pleasures that take up disproportionate space and

importance, the last resort of old men who refuse to be stilled

in their reach for connection, who are still engaged against

the dying of the light.

Beneath

the Rooftops of Paris cannot be accused of being a feel

good film, but it sharpens, like a knife on a stone, our appreciation

for, quoting Marcel Proust, “the places that we have

known belong now only to the little world of space on which

we map them for our own convenience. None of them was ever

more than a thin slice, held between the contiguous impressions

that composed our life at that time; remembrance of a particular

form is but regret for a particular moment; and houses, roads,

avenues are as fugitive, alas, as the years.”