What

is warm in winter is hot jazz, and for its 15th edition Jazz

En Rafale provided the heat and timely “Take

Five” from the cold.

Unlike

last year, which featured the piano, and 2013, the bass, there

was no theme or connective  tissue

linking this year’s six evenings of concerts – except

consistently top notch jazz. However an accidental theme did emerge:

the exceptional performances by some of the rhythm sections, the

buoy and support that underlie every inspired solo.

tissue

linking this year’s six evenings of concerts – except

consistently top notch jazz. However an accidental theme did emerge:

the exceptional performances by some of the rhythm sections, the

buoy and support that underlie every inspired solo.

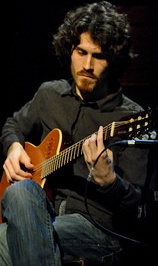

Three

in particular stood out. Backing up Tevet Sela and guitarist Gilad

Hekselman, who lived up to high expectations, were the sublime

Remi-Jean Leblanc on bass and Martin Auguste on percussion. The

complicity between Leblanc and the front men was a lesson in listening

and relating. If the ear didn't catch it you saw it in Leblanc’s

cherubic eyes, the 'kind of blue' you find in a Raphael painting

where the relationship between art and the divine are revealed

in light.

Pushing

Donny McCaslin to the outer limits were bassist Scott Colley and

percussionist Johnathon Blake, who at one extreme coaxed machine

gun like effects from his drum kit, while at the other extreme,

the stealth of a cat looking for its next meal in the dark of

midnight on the moors.

No less

noteworthy in a supporting role was Montreal’s Jazzlab Orchestra

in a rare live performance of Rufus Reid’s colossal Quiet

Pride, a work in four movements inspired by the sculptures

of Elizabeth Catlett.

If

the earth is tilted towards the sun at a 23.5 degrees angle, Donny

McCaslin, no stranger to Montreal, dedicated himself to changing

the tilt, a challenge which inspired him to come up with a novel

interval or scale that conveyed the heights that had to be scaled

as well as the obstacles to overcome – and the tenacity

required to pull it off. Against minimalist compositions, he brings

an exceptionally unique and varied vocabulary. Unlike conventional

fusion, which bridges rock and jazz, his music provides an opportune

bridge for listeners looking to find their way from straight jazz

to free-form. However far out or abstract are his excursions,

there is a subdued but unmistakable lyricism in his playing, which

if you catch before it mutates serves as an excellent point of

entry to the kind of jazz you might normally refuse, which makes

McCaslin an important player in the ever expanding jazz universe.

If

the earth is tilted towards the sun at a 23.5 degrees angle, Donny

McCaslin, no stranger to Montreal, dedicated himself to changing

the tilt, a challenge which inspired him to come up with a novel

interval or scale that conveyed the heights that had to be scaled

as well as the obstacles to overcome – and the tenacity

required to pull it off. Against minimalist compositions, he brings

an exceptionally unique and varied vocabulary. Unlike conventional

fusion, which bridges rock and jazz, his music provides an opportune

bridge for listeners looking to find their way from straight jazz

to free-form. However far out or abstract are his excursions,

there is a subdued but unmistakable lyricism in his playing, which

if you catch before it mutates serves as an excellent point of

entry to the kind of jazz you might normally refuse, which makes

McCaslin an important player in the ever expanding jazz universe.

Among

the festival highlights was pianist Enrico Pieranunzi, who in

the tradition of Italian jazz and classical music (Scarlatti)

brought wonderful melody making to his always exciting and extended

improvisations, all of which were subsumed by impeccable technique.

In the

New Talent Contest, where the winner receives a recording contract

with Montreal’s most prestigious jazz label, Effendi,

The Hugo Mayrand Trio took home the bacon. The pianist's (Jérôme

Beaulieu) and  guitarist's

superb musicianship

easily separated them from the competition, but the runner up

group, Night Clock, was a festival highlight: they brought extraordinary

creativity and invention to their set and offered a credible alternative

metric in respect to the criteria (technique and mastery of instrument)

used to pick competition winners.

guitarist's

superb musicianship

easily separated them from the competition, but the runner up

group, Night Clock, was a festival highlight: they brought extraordinary

creativity and invention to their set and offered a credible alternative

metric in respect to the criteria (technique and mastery of instrument)

used to pick competition winners.

There

were a couple of potentially unsettling developments in this year’s

15th edition. Since Jazz en Rafale is regarded as Montreal’s

purist jazz-only festival, Martin Levac’s homage to the

rock group Genesis was a bit off the wall, despite first-rate

musicianship from the pianist and bassist – no strangers

to the jazz idiom.

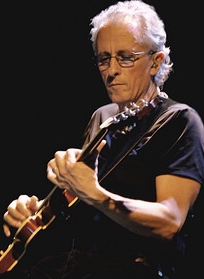

More

controversial was the highlight concert given by the festival’s

official spokesman, Michel Cusson, arguably one of the most significant

composers in the history of Quebec. In the late 70s and 80s, Cusson

headed Quebec’s, if not Canada’s, most famous fusion

band Uzeb, and he has written soundtracks for many movies, mostly

notably Séraphin, for which he was awarded the

Jutra (2003). He also penned the breathtaking music for Odysseo,

the world’s largest travelling tent-horse show. His gifts

as both a musician and composer are self-evident in his vast discography.

Inspired

by his travelling experiences, old photographs and documents,

for the festival’s closing concert Cusson performed -- against

video streaming in the background -- a selection of rock music

that he composed as if writing for film.  As

he describes it, he is exposed to an image or a sequence of images,

a gut reaction follows which he spontaneously translates into

music. Since he was giving a solo concert, to affect the full

sound he desired he had to resort to the controversial technique

of looping.

As

he describes it, he is exposed to an image or a sequence of images,

a gut reaction follows which he spontaneously translates into

music. Since he was giving a solo concert, to affect the full

sound he desired he had to resort to the controversial technique

of looping.

In electroacoustic

music, a loop is a repeating section of sound material, meaning

the musician can write himself a bass line, which he loops, and

then adds as many instruments and effects as required, over which

he performs live. During one of the heavy acid rock tracks, when

Cusson’s equipment manager brought in another guitar from

the wings, there was a necessary pause in his playing but the

looped music continued. For some, I’m sure, it was the equivalent

of a magician revealing his tricks.

From

the composer’s perspective, looping is an invaluable tool.

He can create an orchestra for himself without having to pay the

otherwise prohibitive musicians' salaries. Loops, easily created

and deleted, allow the composer to experiment with all sorts of

sounds, textures and melodies. A work that might ordinarily require

months to be brought to completion can be created in weeks. But

for live concerts, looping is no substitute for relating to live

musicians and the spontaneity we associate with especially improvised

music. Since looping is a strictly mechanical production, its

inclusion redefines the meaning of live performance, much like

lip-synching, now an accepted vocal mode, redefined video music.

Music lovers of course will argue they don’t care how the

music they love is delivered: good music is good music and that

should be the bottom line. Ultimately, audiences who buy the tickets

will determine if looping is to become an integral part of live

performance.

Aside

from the above mentioned questionable developments, Jazz en Rafale

must once again be congratulated for its imaginative and gutsy

programming. Montrealers and winter-resistant tourists were treated

to a range of jazz that reflected and regaled both diversity and

inclusivity.

Rumour

has it that next year’s festival will be dedicated to vocal

jazz – a March time of year I hope to be singing in the

rain.

Photos

© Hanna

Donato