LIKE SHEEP GONE ASTRAY

by

SARAH SCHWAB

Sixteen-year-old

Sarah Schwab is a gifted student who participates in both the

Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth and Stanford University’s

Education Program for Gifted Youth (EPGY). She spends the bulk

of her extra time working as vice president of her own non-profit

youth tree planting organization -- The Tree Amigos of Orcutt.

WHAT

IS ART?

I know

little about art. I am unread about the different periods of

art and I only know the names of a few famous artists. I have

been to a few art museums and have seen quite a number of paintings

and sculptures that I like, but I have never understood why

certain displays are considered art. Many modern art pieces

that I have seen just look like cons. At the Los Angeles County

Art Museum, one of their art pieces is nothing more than a poem

scrolling across the face of a ticker. Or, there is the very

trashed desk with random pieces of wood nailed to it. Sometimes,

such as in the case of the desk, you can choose to make allowances

for artistic expression, and just think that the art world has

gone insane. But, at other times, the ‘artwork’

does not look like it belongs in a museum.

On

the other hand, I have seen a variety of classic paintings in

my history textbooks or in museums. These paintings, such as

the Mona Lisa, are ones that everyone concedes as fitting

into the definition of art. Why do we respond to art in this

fashion? Do we regard an object as art primarily because it

is displayed in an art museum or because someone was willing

to pay thousands, if not millions of dollars for it? Or is it

because we know that the artist intended it to be art? Is there

some artistic instinct resident within us that determines how

we view art? Or is it the combination of any of these elements?

I will attempt to define what criteria an untrained art observer

uses when he makes judgments about whether something is or is

not art.

About

a year ago, I visited the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and

looked at the numerous displays of modern art. At the museum,

I saw the following piece of installation art by Damien Hirst

entitled Away From the Flock.

This

piece of artwork is a lamb preserved in a large box of formaldehyde.

The lamb was not embellished and there was nothing special about

the box that the lamb was in. The only things notable was that

it was a very well preserved lamb and it was in the middle of

the floor of an art museum. When I first saw Away from the

Flock, I was confused. Why would a preserved lamb be viewed

as a piece of art worthy of an art museum? It didn’t seem

any more special then the preserved animals that you see at

science museums or in science classrooms. In fact, if it was

anywhere other than an art museum, then it would be seen merely

as a preserved animal. The Hirst work is an example of something

that we do not instinctively regard as art. Usually, when we

walk down a street and we see paintings or statues for sale,

we think ‘art’” We don’t stand there

trying to figure out why it is art, or whether it really truly

is art. We just know it is art. However, if a preserved lamb

was on the side of the street, we wouldn’t think it was

art. We would just assume that someone had lost their science

experiment or something equally probable.

This

piece of artwork is a lamb preserved in a large box of formaldehyde.

The lamb was not embellished and there was nothing special about

the box that the lamb was in. The only things notable was that

it was a very well preserved lamb and it was in the middle of

the floor of an art museum. When I first saw Away from the

Flock, I was confused. Why would a preserved lamb be viewed

as a piece of art worthy of an art museum? It didn’t seem

any more special then the preserved animals that you see at

science museums or in science classrooms. In fact, if it was

anywhere other than an art museum, then it would be seen merely

as a preserved animal. The Hirst work is an example of something

that we do not instinctively regard as art. Usually, when we

walk down a street and we see paintings or statues for sale,

we think ‘art’” We don’t stand there

trying to figure out why it is art, or whether it really truly

is art. We just know it is art. However, if a preserved lamb

was on the side of the street, we wouldn’t think it was

art. We would just assume that someone had lost their science

experiment or something equally probable.

One

of my favorite paintings that I discovered in my AP European

History book is Primavera by Sandro Botticelli. It

is pictured below.

Before

I saw this painting, I had never heard of Botticelli. I did

not see it in a museum, it was simply in my textbook. This was

just something that I looked at and immediately concluded was

art. If I had seen this painting in any other context -- such

as the background of a PowerPoint presentation, a picture on

a plate, or a poster on the wall, I would have immediately thought

it was art. For some reason, despite its context and my ignorance

of its importance, I automatically and instinctively categorized

this painting as art. But why is this piece perceived as art

no matter what its context, while Away From the Flock

can be art, a curiosity, or a science experiment, depending

on where you view it? Is Away From the Flock really

a piece of art, or have artists, in an attempt to produce new

fresh pieces, become so abstract that they are no longer making

true art?

Before

I saw this painting, I had never heard of Botticelli. I did

not see it in a museum, it was simply in my textbook. This was

just something that I looked at and immediately concluded was

art. If I had seen this painting in any other context -- such

as the background of a PowerPoint presentation, a picture on

a plate, or a poster on the wall, I would have immediately thought

it was art. For some reason, despite its context and my ignorance

of its importance, I automatically and instinctively categorized

this painting as art. But why is this piece perceived as art

no matter what its context, while Away From the Flock

can be art, a curiosity, or a science experiment, depending

on where you view it? Is Away From the Flock really

a piece of art, or have artists, in an attempt to produce new

fresh pieces, become so abstract that they are no longer making

true art?

There

are many people that regard Away from the Flock as a work of

art. If everyone agreed that it was not art, then it would not

be in an art museum. Therefore, as a work of art, it (and Primavera)

should be able to meet the criteria proposed by the various

theories of art.

One

such theory is the formalism theory of art. This theory states

that art must have a specific form. Away from the Flock

definitely has a specific form, since it is an actual dead lamb

in a glass box. Primavera also has a specific form

since it is a painting. However, this is too broad a category.

The car that is parked outside of a person’s house also

has a form, and yet we do not consider it art. So the fact that

Away From the Flock merely exists does not necessitate

that it be considered art.

Another

theory of art is emotionalism. This theory states that for a

something to be art, it must elicit an emotional response in

the viewer. Away From the Flock certainly induces an

emotional response. After all, what person wants to see a cute,

furry little creature dead and preserved in a glass box? The

work might also appeal to our morbid sense of curiosity -- the

same that predicts our fascination with car accidents. Another

response is to wonder what in the world is a dead lamb doing

in an art museum? To that question, one might conclude that

the lamb is not art and therefore does not belong in an art

museum or, that it indeed belongs in an art museum because it

conveys some sort of message, such as only the innocent die

young or individualism -- the act of separating yourself from

others in society.

Primavera

causes an emotional response as well. When you look at it, you

might marvel at the beauty of the three Graces dancing at the

side, or the gentleness of the Venus pictured in the center.

Its intricate detail is fascinating, and you end up with the

impression that it represents all that is gentle and beautiful

in the world. Some might focus on the figures to the right and

say that the painting intends to communicate chaos in the midst

of serenity, while others might focus on Mercury to the left

and say that it represents the fact that nature can slow down

even the busiest of people (Mercury was the messenger of the

gods).

However,

art alone does not cause people to have an emotional response.

For example, many people after 9/11 react emotionally to the

following picture.

This

photograph isn’t the best picture of 9/11. Its image is

blurry and it doesn’t show the critical point of the towers

falling. In other words, this photo is not worthy of being considered

artistic photography. However, it still causes people to have

an emotional response. While causing emotional responses is

an important part of art, it doesn’t automatically mean

that something that inspires a variety of emotions is art.

There

is also the contextual theory, which states that art is whatever

fills the context that society has set aside for it. This is

probably the most promising theory for justifying the notion

that Away From the Flock is art. The context that society

has set aside for art today appears unusual and weird. If displaying

a dead animal as art causes artistic heads to turn, then the

dead animal 'does' fit into the context of what society has

set aside for art. Seemingly, the more unsettling and unusual

a piece is, the more likely it is to fit into the current art

context. It also explains why we automatically think of ‘

art’ when we see Primavera. When the painting

was created, it fit into the context of art that the Renaissance

society had created. It was about a feature of Greek society,

it was beautifully detailed, it represented both the ideal man

and the ideal woman, and its figures were very lifelike in contrast

to the disproportioned and oversized people of the medieval

art world. Despite the fact that it might be disturbing to consider

a dead lamb art, Away From the Flock still fits into

the art context that our society has created, and therefore,

is art.

However,

there are problems even with this theory. The contextual theory

gives any culture, or subculture, that is dominant in the artistic

world at the time, dictatorial control over what is and is not

art. Therefore, it is conceivable that the minority of people,

who are the art critics, have complete control over what is

and is not art. The dead lamb intrigued the art critics while,

at the same time, disgusting other people. Ultimately, the art

critics praised it until it was displayed in a museum. The average

gallery goer, deferring to the more knowledgeable art critic,

agreed that the dead lamb must be art. So, just because a dead

lamb fits into a context that has been created for it, does

not mean that the dead lamb is art. It just means that there

is a select group of people who think that it 'should' be art.

The

same theories that justify Primavera as being art also

justify Away From the Flock. However, these same theories

also qualify many other things as being art, such as the old

beat up car parked in front of somebody’s house.

If

all of these theories fail to definitively determine what exactly

is art, then how can we tell whether Away From the Flock

is art or not? And how can we tell whether a classic painting

such as Primavera is art? I propose that there should

be an additional theory of art that states that for something

to be art, it must be art in all contexts.

For

example, I mentioned earlier that no matter where or in what

context I saw Primavera, I considered it art. It is a well executed

painting, which separates it from the doodles of a monkey or

the finger painting of a two year old. If the painting were

hanging in a kindergarten class along with the scribbles of

the students, and a person was asked to identify the piece of

art on the wall, without hesitation, that person would point

out Primavera. It fits all of the expectations of art

that we have and have had for centuries.

However,

if you took Away From the Flock outside of the context

of a museum, then people would no longer view it as art. If

you put it in somebody’s home, then a visitor would probably

just think that the owner was a scientist or had a disgusting

sense of décor. If you put it in a Natural History Museum,

the lamb would just be seen as an exhibit, along with stuffed

lions and tigers. If it were in a science classroom, it would

just be a way to get students really interested in science.

Because Away From the Flock is only art when it is

exhibited in an art museum, I therefore propose that it is not

truly art.

Many

people will object to this idea, arguing that many of the objects

we consider art have some purpose, such as a Grecian urn. We

display the urn in a museum and call it art. However, the Greeks

certainly did not make the urn and decorate it in order to mount

it unused on a pedestal and admire it. They made it as a jar

to put water or oil in. Are these urns not art because their

original purpose was functional?

The

urns are definitely not art. Remove the embellishments from

the urn and it is just a normal, everyday pot. Instead, the

paintings on the urn are the art and are separate from the urn

itself. When we buy a blank canvas, we do not think that we

are buying a piece of art. Instead we are buying white fabric

stretched over wooden beams. But when we apply paint to it and

make designs on it with a paintbrush it becomes art. A canvas

certainly has a purpose other than to be admired. Its purpose

is to be covered with paint. Or, in times of extreme need, it

can be pulled apart and used to mend a leaking roof or feed

a dying fire. Marble can be used to make a floor or a flight

of stairs. And we certainly do not call a flight of marble stairs

art. They instead are mediums from which art can grow. A canvas

is a surface/material that is necessary to produce a certain

type of painting. Marble is a material used in the production

in certain type of statuary. The urns that the ancient Greeks

used are mediums as well. The urns themselves are not the art.

But the paintings that embellish them are. We cannot separate

the images on the urn from the clay out of which the urn is

made any more than we can separate a painting from its canvas.

Therefore, we display the urn. But we are not admiring the clay

shape anymore than we would admire the square shape of the canvas.

We are admiring its embellishments.

The

reason why items such as Away From the Flock are not

affected by these claims is because there is nothing embellished

about the lamb or the box it is contained in. In Away From

the Flock, the lamb is not just a medium, but it is the

medium and the work of art. There is nothing original or special

about it. The lamb isn’t posed in any unusual way. It

looks just like it is standing. It is not coloured oddly, it

looks like a normal, everyday lamb. The box isn’t constructed

in an unusual way. It is just a standard glass box. It doesn’t

show any special creativity. Anyone can learn how to preserve

a lamb, just as anyone can learn how to make a ceramic pot.

The reason why we admire art is because it requires something

special that, despite years of training, we cannot reproduce.

Another criterion is whether art to be art should be regarded

as such in different cultures. If I exposed Primavera

to a remote African tribe, would they view it as art? They might

view it as something marvelous that the gods gave them to worship,

but not art, which means Primavera would fail the test

because it wasn’t regarded as art in all contexts. However,

just because the culture I live in views something as art, doesn’t

mean that all cultures everywhere view it as art.

What

might be art to one culture may be seen as grotesque in another

culture. However, this objection assumes that only certain civilizations

have developed a form of art, such as painting. That is not

necessarily the case. Various societies that are not large or

highly developed have developed paintings of some form or another.

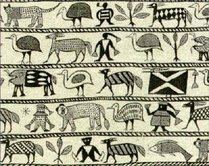

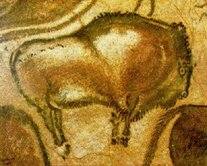

Below are a few examples of art from primitive or tribal societies.

These

different art forms existed before these cultures interacted

with western civilization. Cave paintings, for example, were

created from different pigments being mixed together and applied

to a surface. Whenever we examine ancient cultures, such as

the Mongolian or African, we discover they all have their own

form of art that, except for the method of the execution, are

similar to each other. If I presented Primavera to

an isolated African community, it would not necessarily reject

it as art because its art might share certain values with western

art.

Some

people may also argue that for something to be art, the person

must have put a great deal of effort in creating the piece.

For example, the creator of Primavera probably spent

months creating the fine details of his painting before he decided

that he had created a fine work of art. This would mean that

something such as Away From the Flock would be art

as well. The creator of the piece had to find a lamb, kill it

without marring its appearance, build the glass container, pose

the animal, and fill up the box with formaldehyde. All of those

steps are not things that the average person would be able to

do. So, because of the effort that was put into a certain piece’s

creation, that is what makes it art.

If

this were true, everything manufactured would be art. A Hersey

bar would be art because someone had to spend a lot of time

creating chocolate, and someone else had to invent a way of

mass producing the chocolate. The problem with this idea is

that it confuses the primary definition of art with the secondary

definition. The primary definition of art is “the conscious

use of skill and creative imagination.” However, the definition

that this objection uses is a “skill acquired by experience,

study, or observation.” There is a difference between

the two definitions of art. The art that we appreciate and put

in museums requires “creative imagination.” The

art that making a candy bar requires is a skill. Art requires

more than just skill. It must involve a creative process that

makes the piece of art somehow unusual and special.

A final

objection is that people may argue that this theory or definition

of art greatly limits the creative scope of what an artist can

do. Away From the Flock was a revolution in art and

should be respected because it breaks away from traditional

ideas and limitations on art. You can still make a statue of

a giant clothes pin and display it as art, or paint the bottom

of your shoes and walk across a canvas and call it art. There

are still an infinite number of things you can do with paint

that can alter how we see art and what we think art to be. However,

anyone can install a toilet in the middle of a museum floor,

or preserve a lamb in a large box of formaldehyde. Doing things

like that show no creative talent, other than the talent of

convincing people that a very ordinary object is somehow extraordinary

enough to be considered art. If anything, this theory will force

artists to be more creative and create more artistic innovations.

Art

has always been a very tricky thing to define. Ever since the

first drawings in caves were made, there has been a debate about

what is, and what is not art. However, displaying ordinary objects

in art museums is not art. It takes no creativity to put a lamb

in formaldehyde and put it in a museum. It just takes moxie

to convince a critic that the lamb is art. Part of what makes

art so wonderful is the effort that the artist puts into it.

Finely detailed paintings are seen as classic pieces of art,

not just because the paintings are beautiful, but because you

can see how much thought and effort the artist put into making

it. Art is more than just the finished project. It is all of

the hard work and new ideas that were put into creating it.

Related

Articles:

INSTALLATION

ART OR ARTIFICE

SAVING

THE VISUAL ARTS

ABSTRACT

ART ISN'T ART