NOTES ON SILENCE

by

YAHIA LABABIDI

__________________

Yahia

Lababidi, Egyptian-Lebanese poet and thinker, is the author

of Signposts

to Elsewhere, elected for Year in Books (Sun

Sentinel, USA, 2007) as well as Books of the Year (The

Independent, UK, 2008). Lababidi's aphorisms are included in

an encyclopedia of The World's Great Aphorists, while

his poetry and essays have appeared throughout the US, Europe

and the Middle East.

It may seem like

a betrayal to speak of silence, to break an unspoken pact. Yet,

whether we are conscious of it or not, it is there, inextricably

woven into the fabric of our lives. As Sufi poet Rumi writes,

“a person does not speak with words. Truth and affinity

draws people. Words are only a pretext.” It exists in

the gaps between our words and encounters with the natural world.

In fact, silence is a platform from which we observe and interrogate

ourselves and our world.

What’s

more, silence is a prerequisite for certain vital solitary activities,

such as contemplation, meditation, prayer, healing, as well

as overhearing the dictates of our conscience.

But,

ubiquity does not ensure intimacy. Thus, silence, this quiet

capital of riches, is both under-considered and undervalued.

Perhaps by learning to recognize our silences in their many

guises, we may begin to demystify them and make them more intimate.

Whether

longed for or reviled, summoned or thrust upon us, silence is

an inescapable force in our lives. Yet curiously, as a discipline,

Western Philosophy seems not to have deeply investigated this

constant presence -- leaving it up to spirituality, poetry and

psychology to explore this elusive territory. Perhaps for philosophers,

maddened by their own music -- as they tend to be -- this slippery

subject is perceived as a kind of rebuke to philosophy’s

lust for logic and systems. In the words of that rare Western

philosopher, Wittgenstein, who acknowledges the limits of reason

and the sayable: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one

must be silent.”

Yet

contemplatives,

poets and thinkers alike, have long hinted at a wisdom beyond

words, straining the limits of language and sense, to describe

the ineffable. And, even if this love of silence (and attendant

solitude) is not explicitly expressed in works of philosophy,

it is behind the scenes in the lives of philosophers, often

informing their utterances and positions. This is the case of

that great solitary thinker Friedrich Nietzsche, for example,

who wrote in Thus Spoke Zarathustra: "It is the

stillest words which bring the storm. Thoughts that come on

doves’ feet guide the world." Likewise for Samuel

Beckett who, in his plays, seemed to be heading towards silence

-- such that, in works like Breath or Act Without

Words, it almost comes to overtake speech.

Still,

rather than being defined negatively -- as the absence or perhaps

failure of words -- silence may instead be viewed positively

as somehow existing before and beyond representation, a primordial

essence that lurks beneath our constructed world. In the immortal

formulation of Tao Te Ching: “Returning to the root is

silence/Silence is returning to being.” Just a pause in

speech can offer us an unexpected glimpse of this -- sending

us spiraling down the black hole of silence, where matters are

more dense, and consciousness itself seems more intense. As

the silence-revering writer Emile Cioran observes, “A

sudden silence in the middle of a conversation suddenly brings

us back to essentials: it reveals how dearly we must pay for

the invention of speech.”

It

is, in silence, that things patiently unfurl, open up and trust

us with their secrets, or reveal their hidden natures -- be

they shy ideas or creatures, daybreak or a work of art. In this

fundamental and seemingly privileged state, what seems to elude

the world of words and sound may otherwise appear to dawn on

us; perhaps since we are now in the position to overhear ourselves

and tell ourselves that which we already know. Unsurprisingly,

realizations and revelations are forged in this realm. Silence

is, after all, the best response and conduit for our most profound

experiences: Awe, Love, Death.

THE

MANY SILENCES

Cultivating

silence can also mean cultivating attention, so that we are

present to ourselves and the deeper life that is continually

unfolding within and around us. We may begin to do so by investigating

the silences available to all of us, knowing them better as

well as their judicious uses. Three categories we can explore

in some depth are: silence as language (wordless communication),

as entity (physical presence in nature) and as a kind of metaphysical

portal (for contemplation, meditation, transcendence).

As

a language, silence can be the thing and its opposite: eloquent

or clumsy, despairing or serene. It can be polite, communicating

respect, empathy, or even a form of restraint - - i.e. abstaining

from unkindness, or being drawn into argument or pernicious

gossip. Or it can be impolite, transmitting anger or hostility

-- such as a sullen, resentful silence.

Moreover,

it can mean varying things within different cultural contexts.

For example, a silence that is considered socially embarrassing

or awkward in a Western setting is not at all in parts of the

Far East (such as China or Indonesia). In fact, the contrary

can be true. Most notably in Japan, where silence is deeply

valued; it is eloquence that is regarded with suspicion, since

verbosity is often associated with a certain superficiality.

In Japanese, there is even a word for wordless communication

-- haragei -- used to refer to the preferred modes

of expressing emotional matters.

Which is to say, as a means of wordless communication, silence

is as fluid and protean as the emotions and situations it is

born of, often conveying what words cannot. As poet Rainer Maria

Rilke confesses: “Things aren't so tangible and sayable

as people would usually have us believe; most experiences are

unsayable, they happen in a space that no word has ever entered.”

With

their arsenal of ravishing phrases, poets are perhaps most acutely

aware of how words fail us; are not there when we reach for

them. Here is T.S. Eliot elegantly bemoaning the shortcomings

of his bread and butter:

What’s

more, not all of us have the right words, or find them at all

times. Such as when silence lodges itself in our mouth or throat,

when we are handed an unexpected piece of bad news, leaving

us stunned and speechless. Confronted with the enormity of a

situation, we are simply left with a silence that is as authentic,

integral and universal as body language; shrugging off the need

for words, altogether.

As

an entity too, Silence can be difficult to define. For it is

not merely the absence of sound, but may be perceived as an

actual physical presence, as well. The elemental silence found

in the natural world is a case in point: whether it is relative

(in the forest, or underwater) or absolute (as within the desert,

before a storm or, ultimately, in outer space). There may be

grades to silence in the natural world, but such encounters

with it as an entity may be said to represent a kind of auditory

equivalent to stillness.

Anyone

who has crept upon a morning, for a stroll at dawn knows this

holy hush. Just as someone who has experienced sound swallowed

whole in the mysterious silent underworld of the sea, or drunk

deeply of the quietude of desert air will also be familiar with

this sense of the numinous -- where Time appears to collapse

and one is afforded glimpses into Eternity. Great beauty silences.

Even if accompanied by the rich tapestry of the sound of creatures

quietly going about their daily affairs, silence is the solemn

companion of nature enthusiasts and can presence like the very

pulse of Being.

Anyone

who has crept upon a morning, for a stroll at dawn knows this

holy hush. Just as someone who has experienced sound swallowed

whole in the mysterious silent underworld of the sea, or drunk

deeply of the quietude of desert air will also be familiar with

this sense of the numinous -- where Time appears to collapse

and one is afforded glimpses into Eternity. Great beauty silences.

Even if accompanied by the rich tapestry of the sound of creatures

quietly going about their daily affairs, silence is the solemn

companion of nature enthusiasts and can presence like the very

pulse of Being.

Here

is how spiritual teacher, Krishnamurti, describes this mystical

state: "And it is only where there is space and silence

that something new can be that is untouched by time/thought.

That may be the most holy, the most sacred -- may be. You cannot

give it a name. It is perhaps the unnamable.” Grappling

with such mysticism and the unnamable is harder for philosophy,

but the younger Kant makes an attempt at it: “In the universal

silence of nature and in the calm of the senses the immortal

spirit’s hidden faculty of knowledge speaks an ineffable

language and gives [us] undeveloped concepts, which are indeed

felt, but do not let themselves be described.”

Yet

another category of silence is that of portal. One is said to

‘enter’ and ‘emerge’ from this state,

as though it were an actual physical territory. We cannot forcibly

break-in and enter, or rush through this portal to arrive at

a meditative-reflective state; but instead must patiently wait

to be granted access. Sculptor Rodin’s Thinker

is a monument to this invisible art of turning inward. He is

not seen surrounded by others, in the midst of conversation,

but rather depicted quite alone -- lost in thought and found

in silence.

There

are also temples of silence -- secular spaces of worship, study

and healing where silence is cultivated, such as: libraries,

museums, hospitals, cemeteries and prisons. On account of the

intellectual, moral, or spiritual seriousness of such spaces,

they foster a certain respectful reflection, thereby permitting

us to pass through this silent portal.

Reading,

can act as a springboard to access this region of the soul,

where one is transported, and our external surroundings seem

to fall away like so much dead skin (to the extent we may even

become oblivious of our own bodies). Extolling the pleasure

and spiritual edification of the written word, bibliophile Susan

Sontag describes reading as “that disembodied rapture

. . . trance-like enough to make us feel egoless.”

Quiet

reverie, or the art of (apparently) doing nothing might be another

route to ‘disembodied rapture,’ and can also serve

as an escape from the tyranny of Self, Space, and Time. Within

this realm, we are free to travel backwards and forwards, conjuring

up both memories and fantasies. Not as frivolous as this may

seem, such flights of imagination are necessary for our sanity,

affording us a creative space for playful inner work and a restorative

psychic flushing out (of daily toxins such as pressure or worry).

Obviously,

prayer is a central portal to access this condition of blissful

silence. We see it prescribed in Sufi wisdom writings stressing

the significance of seeking inner silence, or Buddhist injunctions

to let the mind become silent to attain enlightenment, or in

Quakerism, as a feature of worship, where silence is an occasion

for the divine to enter the heart. More extremely, in the case

of Trappist monks, a life-time commitment to silence aims to

foster solitude in community as well as a mindfulness of God.

All of these varying notes reverberate in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s

inclusive definition of prayer as “the soliloquy

of a beholding and jubilant soul.”

Meditation,

without silence, is inconceivable. Here, stillness and self-emptying

are requisite in order to attain any kind of calm or peace.

In mysticism -- perched as it is on the precipice of all organized

religions -- Rudyard Kipling is repeatedly refuted, and the

East and West do regularly meet. In the pregnant prescription

of one who devoted an entire book of thoughtful meditations

to this subject, Christian philosopher Max Picard: “Silence

is listening.” And, as attentive practitioners of this

metaphysical art may sense, it can sometimes be unclear who

is doing the actual listening… us, or Silence itself.

Otherwise,

dissimilar spiritual traditions -- Hindu, Buddhist, Taoist,

Jewish, Christian, Muslim, and Native American -- all agree

on the importance of observing silence as a tool for inner growth/self-

transformation. More recently, based on scans of Buddhist monks’

brains, the young science of Neuroplasticity indicates that

meditation actually alters the structure, and functioning of

the brain. In other words, our thoughts and silences can, in

effect, change our minds, and even our lives: the ultimate goal

of philosophy or religion.

Moreover,

these three categories of silence -- communication, entity and

portal -- need not inhabit separate spheres and exist in the

same medium. For example, while in media technology -- i.e.

television and radio -- silence is perceived as ‘dead

air’, the three silences are successfully employed to

dramatic effect within the Arts. This is evident in theatrical

work, or a piece of music, or even stand-up comedy where silence

may be used to communicate nuance and depth, or else serve as

a pause for reflection on the parts of viewers and listeners.

CULTURE

OF NOISE

Perhaps

more than ever before, it has become necessary to speak up in

praise of silence, as an attempt to redress the balance in a

cacophonic contemporary culture that appears alternately suspicious

or outright contemptuous of silence. Living as we do, in the

busyness of this modern world -- hooked up, beeping and under

the false imperative of needing to keep in touch with everything

-- we find ourselves in the unhealthy situation of losing our

silences and the sustenance that comes with them.

So

we desperately rush, hurling ourselves from one activity to

the next, without ever pausing to process what it is we’ve

learned, or dilute the concentration of experience with reflection.

To combat the distraction of noise, we may turn to the discipline

of silence which, practiced consciously, can be as much of a

renunciation as fasting -- or the ascetic exercise of denying

the physical body in order to nourish our spiritual entity.

As

it is, the erosion of silence in our lives is unmistakably connected

with our noise-ravaged nerves, or increased stress levels, as

well as increasingly shortened attention spans. This, in turn,

negatively affects our ability to both think and feel deeply

in order to sift through the deluge of stimulus that informs

our hurried and harried days. To the list of offenses resulting

from the loss of our silences we may add the corruption of the

art of conversation; since no matter how effortless or ephemeral

good talk may sound it is invariably rooted in, and the product

of, sustained private reflection.

Previously

a portal to silence, the culture of reading is currently imperiled

in favor of ‘information snacking’ to accommodate

our hectic schedules. This, coupled with the media’s shrill

and insistent competition for our attention, makes it necessary

to guard our silences even more vigilantly. In this context,

for example, we can more closely examine how the Internet affects

our concentration and capacity for critical thinking. (Author

Nicholas Carr’s critical and provocative article, "Is

Google Making Us Stupid?: What the Internet is Doing to Our

Brains" -- The Atlantic, July/August 2008 -- might

serve as a thoughtful point of entry regarding this controversial

debate).

If

French philosopher Blaise Pascal is correct, that “all

of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability

to sit quietly in a room alone,” then the proliferation

of talk and reality shows may be seen as symptomatic of our

cultural malaise. Namely, reality shows, which actually serve

to distract us from reality, or being present to ourselves,

are precisely a reflection of our collective “inability

to sit quietly in a room alone.”

Just

like silence, noise, too, can be the absence of sound. Noise

is also the silent invasion of our inner spaces by the clutter

of undigested information and unsorted emotions that pile up

throughout the days and weeks. With our private spaces thus

encroached upon, we risk becoming alienated from ourselves until

our lives are something foreign to us.

Rather

than allow ourselves to be shoved into the bathroom -- perhaps

the last sanctuary of personal space and reflection -- we should

instead question the necessity or merit of amusing and multi-tasking

ourselves to death. Against the odds, of what at times appears

to be a conspiracy of noise, we must try to assert our birthright

to retreat, reflect and regenerate.

Solitude

tends to produce an understanding of our own limitations, and

forces us to seek our own council in dealing with them. And,

in turn, the insights and greater self-awareness attained in

solitude eventually need to be tested in the company of others.

Emerson

sums this up succinctly: “it is easy in the world to live

after the world's opinion; it is easy in solitude after our

own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps

with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.”

Yet,

silence, like any controlled substance, must be handled with

care. Initiates, or masters of silence -- such as solitaries,

thinkers, monks, hermits, and ascetics -- have long known how

to mine it for fortitude and insight, or to arrive at ecstasis

(to be or stand outside oneself). But it is up to each individual

to determine how much is desirable or useful; as too much of

this good thing might be counterproductive for some, even dangerous

-- leading to despair, madness or even suicide.

Just

as the monastery and institutionalized silence are not for everyone,

so too extended travels to the foreign land of silence are not

for tourists. Snake-handlers of the spirit -- those versed in

playing with dangerous things -- may engage deeply with the

death-in-living that is desert dwelling, the soul-trials of

solitude, or even their own shifting images in the mirror. Others,

less practiced, might not endure such extreme experiences (of

the Limit), and might emerge damaged. Which is to say, striking

out fearlessly into treacherous, interior territories is not

for dilettantes; and deep and prolonged silence might prove

the undoing of those who flirt with it, ill-equipped.

“Social

intercourse seduces one into self-contemplation,” muses

writer Franz Kafka. The aim, then, is to try to find that healthy

balance -- between silent fasts and noise feasts -- on the slippery

road to moderation.

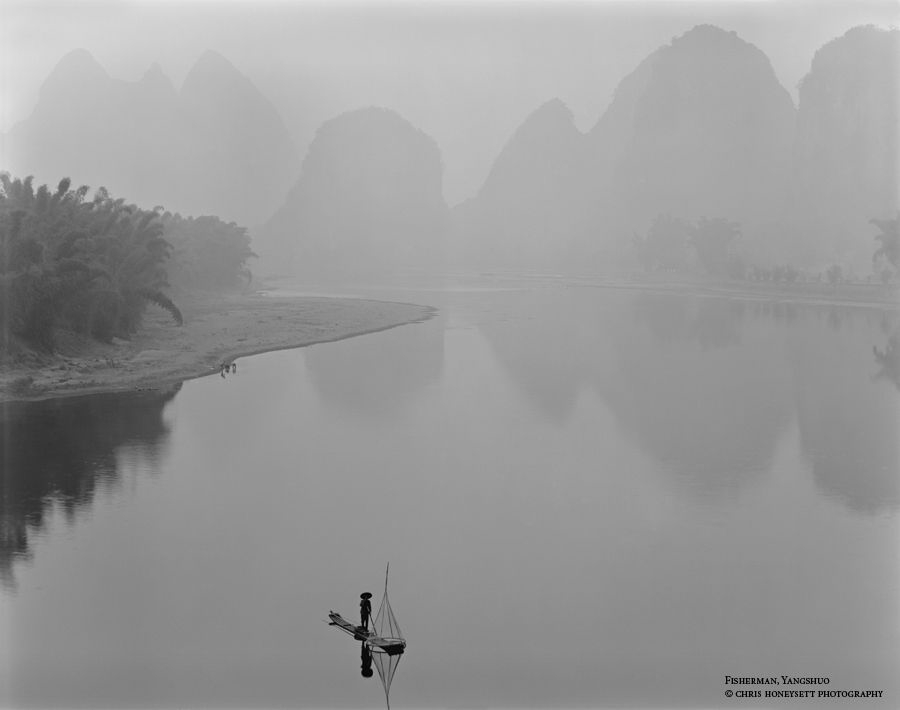

Photos

courtesy of © Chris Honeysett =

www.chrishoneysett.com

Related

Articles:

Heidegger

and Silence

Nature

at Dawn