With this first paragraph

of Philip Roth's first book, a career begins, resoundingly.

It evokes youth, beauty, hope -- mostly hope of love. All are

embodied in Brenda, the cool, self-assured water nymph. But

this naiad wears glasses, and her last name turns out to be

Patimkin. That she is a mere vulnerable human like us all, with

her virtues and flaws, deepens her appeal. I felt that appeal

when I first read the book, as a teenager. Now, rereading it

many years later, I felt it again.

It

is Neil who is given the honour of holding Brenda's glasses,

and it is he who tells the story. He does so with a bright clarity--

the youthful Roth's prose has a freshness to it, an original

snap -- as in Brenda's cheeky catching of the bottom of her

suit and flicking "what flesh had been showing back where

it belonged."

Goodbye,

Columbus spans one summer. And no more. The fervent glow

of love that Roth captures so well does not survive the complexities

of life. A diaphragm is the purported devise that leads to the

break-up. I say "purported" because the end of the

affair feels imposed on the plot (with Neil being the author's

co-conspirator). On the closing page, after leaving Brenda in

a hotel room, Neil thinks, "I was sure I had loved Brenda,

though standing there I knew I couldn't any longer. And I knew

it would be a long while before I made love to anyone the way

I had made love to her. With anyone else, could I summon up

such a passion?"

But

absent from his musings are despair and fear and doubt. It seems

that, in leaving Brenda, Neil is making a decision: saying goodbye

to one life -- the conventional and enveloping one he doesn't

want to be part of, the world of the Patimkins -- and resolutely

turning toward another.

In

this light the title, Goodbye, Columbus, is meaningful.

Ron, Brenda's older brother, attended Ohio State University

and was given a record when he graduated. He plays it for Neil.

A Voice intones: "Life calls us, and anxiously if not nervously

we walk out into the world and away from the pleasures of these

ivied walls. But not from its memories . . . ." "We

shall choose husbands and wives, we shall choose jobs and homes,

we shall sire children and grandchildren, but we will not forget

you, Ohio State . . . ." The record ends with a litany

of goodbyes: "goodbye, Columbus . . . goodbye, Columbus

. . . goodbye . . ."

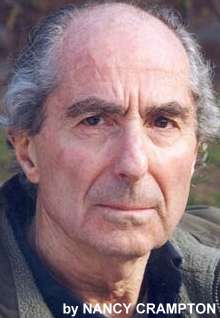

Because

Philip Roth has, over the years, been a strongly autobiographical

writer, I cannot but think that there was a Brenda in a summer

of his youth. And though, in the novella's last paragraphs,

Neil gazes through the window of a darkened library, closed

for the night, looking at a wall of books, it is not the dull

life of a librarian that the young man is seeing in his Brenda-less

future.

*

* * * *

What

life was beckoning to Philip Roth? It turns out that 27 of the

books in the world's libraries would be written by him. Roth's

life would be one of tremendous literary success. Goodbye,

Columbus was published in 1959, when Roth was twenty-six.

The five stories that go with the title novella appeared in

elite magazines: Paris Review (where Goodbye

also appeared), The New Yorker, and Commentary.

The book received the National Book Award. Out of the starting

blocks, Philip Roth was a major novelist.

Not

only was he a uniquely-talented, early bloomer, but he was ambitious,

focused, intelligent. At the age of sixteen he went to Bucknell

University and got a degree in English. From there he moved

on to the University of Chicago, where he received a M.A. in

English Literature and then stayed to teach creative writing.

It was while in Chicago that he met his mentor, Saul Bellow.

Roth taught creative writing at various universities, including

Iowa. He made all the right moves. But that's what you have

to do. And, in his case, there was that talent.

Philip

Roth has lived almost 50 years since Brenda dove into the pool.

In his long career the achievement he will be ever-associated

with is Portnoy's Complaint. That comic masterpiece,

that howl of rage, in all its glorious vulgarity, plumbs themes

that have preoccupied him his whole career -- sex and Jewishness.

Tangled themes for him, and from inside the tangle not much

light escapes.

Philip

Roth has lived almost 50 years since Brenda dove into the pool.

In his long career the achievement he will be ever-associated

with is Portnoy's Complaint. That comic masterpiece,

that howl of rage, in all its glorious vulgarity, plumbs themes

that have preoccupied him his whole career -- sex and Jewishness.

Tangled themes for him, and from inside the tangle not much

light escapes.

I heard

him interviewed by Terry Gross on "Fresh Air" in 2001,

and he talked a bit about his personal life. I learned (as I

drove through a rainy night) that he had some serious illnesses,

including heart bypass surgery. He had a terrible bout of depression

but was saved by medication. He sees no purpose to life and

has no religious beliefs (indeed, he is strongly anti-religious).

His two unhappy marriages, which were childless, were not mentioned

(of course they weren't, though they have provided material

for Roth's novels). I got the impression that he lived alone.

He

was a difficult interviewee. At times he would respond to a

question by questioning Terry about her question. He did this

in an intimate, gently toying manner. I found his subversion

of the rules of the interview refreshing. (Keep the questions

intelligent and straightforward or you're going to get them

back.)

He

said that he writes, writes, writes in his home in the Connecticut

countryside. It seems that writing is his reason for living

-- his saying to himself and to the world: I can create, I exist.

It is a way to stave off the darkness.

Philip

Roth may produce many more novels, but in a way Everyman

is his last. It's about the end of life, a goodbye to life.

How much time is left to him? He is not the young man of Goodbye,

Columbus, with a fresh new world stretching ahead.

I

wonder if he sees a form of immortality in the worlds he has

created. People a 100 years from now may read his books, and

his characters and situations will come alive in their minds.

Brenda will rise from the pool, Neil's blood will jump. Does

the author come alive too, in some sense?

* * * * *

Everyman

begins at a graveside. I had wanted to start this section with

Everyman's opening paragraph, as I did with Goodbye,

Columbus. But it's a long paragraph, and it doesn't have

the immediate accessibility (nor that "snap") that

the other one does. I don't mean that it isn't good writing,

or that it's boring. It's entirely appropriate to the novel's

subject matter. But young love and death are poles apart, and,

let's admit it, we'd rather be at the poolside than the graveside.

In

fact, I had qualms about reading this book. I thought of it

as an ordeal I would have to suffer through.

I was

surprised. The book was not gruelling to read. I know Roth can

be raw, but he chose not to be. For example, the unnamed narrator

(I'll have to call him Everyman) has open heart surgery, but

the gory details of that surgery -- the sawing through the rib

cage, the removal of veins from the legs -- are not described

(though Everyman must surely have thought long and hard about

the procedure). He has scars from the operation, and Roth simply

states that fact.

In

this short novel Roth explores, with care and honesty, the emotional

state of a man facing the end of life.

On

the surface this is not an autobiographical work. Roth's Everyman

is not a successful author. He's a man who had a lucrative career

as a commercial artist, and upon his retirement he turns to

painting. But he realizes that he has no real talent. He acutely

feels the hollowness of not having the consolation of being

able to create art. He is left with nothing -- just "the

aimless days and the uncertain nights and the impotently putting

up with the physical deterioration and the terminal sadness

and the waiting and waiting for nothing."

That

said -- that Roth does not use many outward facts from his own

life -- there is an emotional authenticity. After all, is Roth

not Everyman? Despite his considerable success, and the purpose

his writing must give to his days, Roth must face what his character

does.

His

Everyman lives alone, is lonely; he has a loving daughter (who,

though supportive, does not live near him) and a dear brother

(who he breaks from, in "a sick man's rage" at the

happy, ever-healthy, contentedly-married Howie). Those two --

daughter and brother -- will be the only ones at his graveside

who deeply care for him. He has regrets, remorse, mostly concerning

his failed relationships with women and his long estrangement

from his two sons. He is beset with desire for the young women

he sees jogging as he sits on the boardwalk, a desire that he

knows must go unfulfilled. More loss - that of sexuality. Nothing

can answer his needs, for he has the elemental need to be what

he once was.

He

fears helplessness and death. For this Everyman, who has no

religious beliefs, death is oblivion, simply ‘not being’

anymore, and the void terrifies him.

"You

just take it and endure it," Everyman thinks; the novel

shows how very hard it is to do that.

Yet

the book is not all grimness. Other feelings are elicited in

the reader. Everyman is a decent, compassionate man (the scene

with the suffering Millicent is especially touching). And, since

I mentioned a scene, there are others that are done masterfully

-- Everyman's encounter with the young female jogger and his

talk with the gravedigger. Howie's farewell speech at the gravesite

(beginning with "Let's see if I can do it. Now let's get

to this guy. About my brother . . .") is a moving monologue

in which Howie does indeed "do it." There is pleasure

for the reader in such prose. There are some graphic sex scenes,

and a burst of rage at his unforgiving sons -- parts that, for

me, struck a discordant note -- but these are exceptions to

the rule. At one point Everyman muses that his "combativeness

had been replaced by a huge sadness."

One

refuge for Everyman are memories of the distant past. He must

go back -- back past his adulthood and his teenage years --

to a time when he was capable of a purity of emotion. His father,

mother and Howie kindle tender memories. He feels a nostalgia

for his father's jewellery store. During his many angioplasties

he distracts himself, as they insert the arterial catheter,

"by reciting under his breath the lists of watches he'd

first alphabetized as a small boy helping at the store after

school -- 'Benrus, Bulova, Croton, Elgin . . .'"

And

he repeatedly remembers riding the big waves of the Atlantic,

sunlight blazing off the water. The vitality of the boy with

the unscathed body in its exhilarating struggle.

Ah,

Life! Everyman sees, as if peering through the jeweller’s

loupe engraved with his father's initials, "the perfect,

priceless planet itself -- at his home, the billion-, the trillion-

, the quadrillion-carat planet Earth!"

Then

the author extinguishes it forever. As he must.

Also

by Phillip Routh:

The

Sea Gull

The

Rise and Fall of Jerzy Kosinski