DEATH WISH 7 BILLION

by

ROBERT J. LEWIS

_____________________

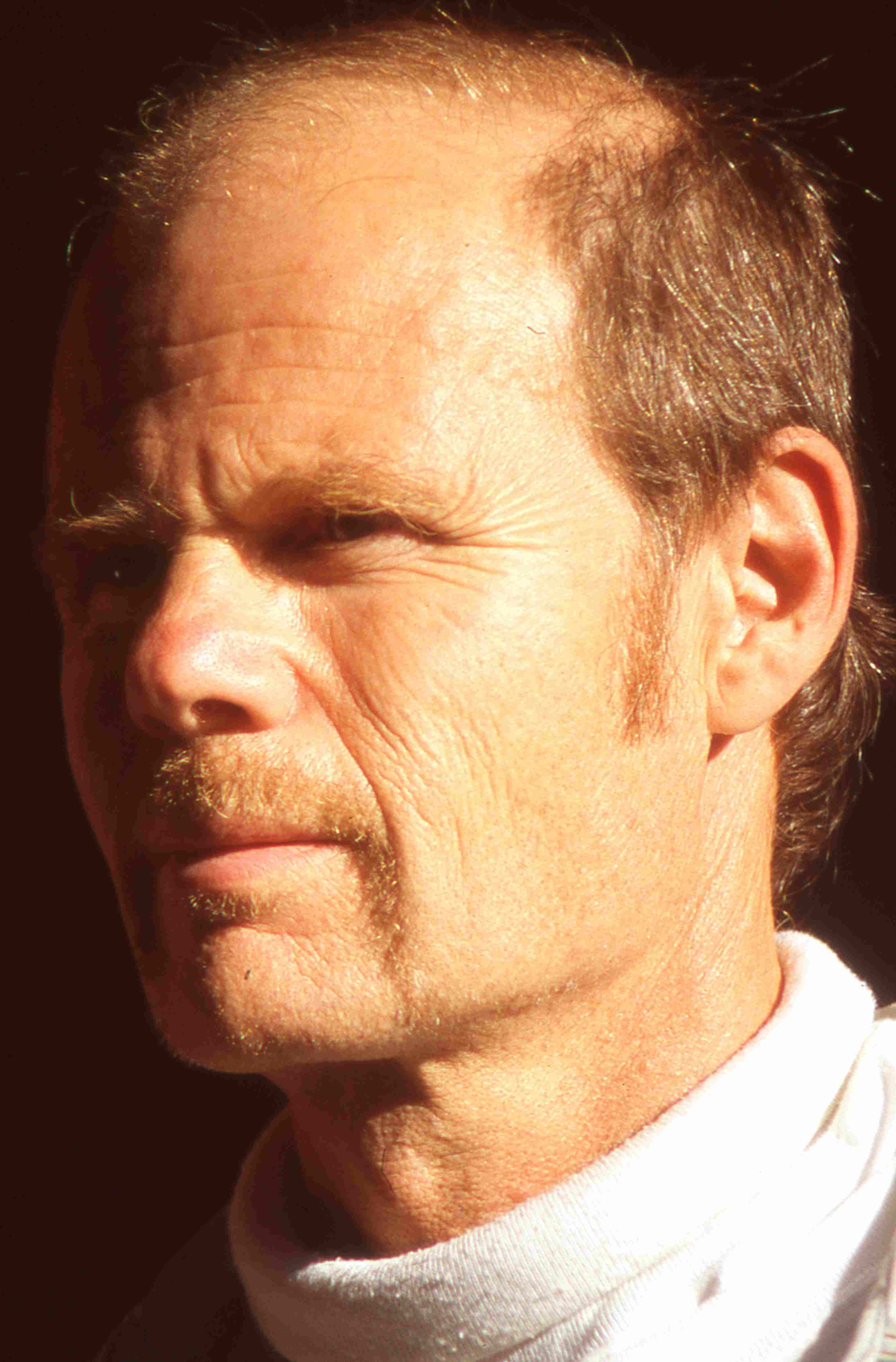

According

to Freudian analysis, the man in the movie who has raped and killed

the father’s only daughter is expressing a death wish, which

Charles Bronson, at the end of two hours, is only too happy to

oblige. Since the guilty party about to receive his comeuppance

is prepared to kill in self-defense, Mr. Bronson is expressing

his own death wish, to which Freud would answer with a sniff and

shrug: no surprise there. The Death Wish films, beyond the edifying

entertainment they provide, offer not so subtle glimpses of Freud’s

theory in full operation.

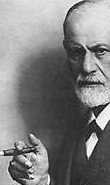

In

Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1922), Freud postulated

that all humans entertain an unacknowledged death wish or wish

to return to “the inanimate,” which he sums up as

the universal desire to commit suicide. Freud, the Columbus of

the mind’s deep, who was also inordinately fond of cocaine,

goes on to say that “the aim of all life is death,”

that the latter forces an appreciation of the transient former

with the death wish supplying the connective tissue.

In

Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1922), Freud postulated

that all humans entertain an unacknowledged death wish or wish

to return to “the inanimate,” which he sums up as

the universal desire to commit suicide. Freud, the Columbus of

the mind’s deep, who was also inordinately fond of cocaine,

goes on to say that “the aim of all life is death,”

that the latter forces an appreciation of the transient former

with the death wish supplying the connective tissue.

Of all

Freud’s theories, the majority of which have been rejected,

the death wish in particular strikes us as pretty far-fetched

as we pursue our Saturday night bowling careers and Sunday afternoon

picnics in the park. But what if these activities aren’t

as innocent as they seem, that their universal appeal reveals

states of mind that in fact support Freud’s claim, especially

if what are enjoyable in bowling, picnicking and the weekend rave

party are not so much the activities in themselves but their diversionary

agency and pleasurable deadening effects on the mind.

All of

us, in varying degrees, are uneasy when in the presence of the

unknown, which is why when we succeed in making something known,

the mind is allowed to rest easy, which is its reward. This is

how it has always been, and since death is unknowable, all cultures,

in turn, are obsessed with with making it known -- the fact of

which does not necessarily translate into a death wish. One could

plausibly argue that our curiosity about death is in fact our

disguised fear of it (the unknown), and we flirt with it not because

we long for it but want to make its acquaintance in order to allay

our fears.

When

we deliberately undertake (or enjoy attending) life-threatening

pursuits such as high speed events or violent contact sports,

are we, as some Freudians propose, expressing a subconscious death

wish? The sport of boxing satisfies the death wish only in the

sense that we subconsciously hope to witness ‘someone else’s’

death, and beyond that, the fallen boxer’s miraculous resurrection,

which satisfies our longing for immortality. That all cultures

indulge in some form of lethal sport speaks only to the fact that

we are incurable as it concerns our curiosity about death, and

we countenance high risk behaviour because it allows us precious

glimpses into the acts and facts of dying and death.

If there

is a Freudian death wish that operates through all of us, it is

revealed in our universal desire to temporarily seek out non-subjective,

quasi-mammalian states of (un)consciousness. The reasons for this

bear directly on the kind of intelligent life we are and persistent

inability to deal with the implications of self-consciousness.

The discomfiting

effects of being self-aware issue from a locus of feelings that

are directly related to how we are affected by the gaze of the

other. Much of our behaviour is determined by the other from whose

judgment there is no formal escape, which is why we dress one

way in public and another in private. In our quotidian we are

constantly negotiating societies (workplace, the mall, restaurant

dining), whose codes and protocols allow no respite from self-consciousness

-- and to such a degree our constitutions eventually revolt because,

in the long consideration of the evolution of life, being self-aware

is a very recent development and we simply haven’t had enough

evolutionary time to adapt. On top of which humans are the only

species that can call itself into judgment (which can give rise

to shame), that requires a purpose in life ( which can cause despair).

André Malraux, in The Voices of Silence, writes:

“when we see a meadow ablaze with the flowers of spring,

the thought that the whole human race is no more than a luxuriant

growth of the same order, created to no end by some blind force,

would be unbearable, could we bring ourselves to realize all that

the thought implies.”

It is

self-consciousness and all that it implies that is too much with

us, which accounts for our universal attraction to the opposite

state, that led Freud to hypothesize a universal death wish, which,

incidentally, does not contradict the pleasure principle since

we all enjoy being relieved of our subjectivity.

In light

of the fact that humans have never been comfortable in their self-conscious

skins, they learned very early in the game that if they could

knock out the neo-cortical functions responsible for self-consciousness

they would revert back to non-subjective states of being. To this

end, humans have been brilliantly inventive in providing for the

activities and ingestibles which facilitate this marvellous short

circuiting, for there is no apparent cure for self-consciousness

other than to desensitize the area of the brain responsible for

it. Which is why when humans, if only fortuitously, manage to

catch glimpses of themselves in the truth of their being, they

rudely discover that “the will to power” seamlessly

accommodates the “will to lobotomy,” – which

the facts on the ground bear out: from time immemorial Man has

arguably been at his happiest when surrendering to the DNA-deep,

anti-ipseity impulses that reside within.

What

unites all cultures in a common cause are the socially sanctioned

customs and institutions that offer relief from self-consciousness.

From the consumption of alcohol and drugs to the obliteration

of the other in the darkness of the cinema or atavistic setting

of the sports arena, we are uncompromising in the ‘wish’

to anaesthetize those faculties of judgment upon which, ironically,

our very humanity is grounded. Even the arts, presumably serving

our edification, have been bent to serve mind-numbing ends. The

sharpest mind will shut down after being exposed to the high octane,

one-note pounding that characterizes Rap music or the endless,

one-note drone that distinguishes India’s songbook. In the

visual arts, monochromatic painting, otherwise known as Minimalism,

serves the same narcoleptic end.

In Dancing

in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy (2007), Barbara

Ehrenreich reports that in medieval France one in four days was

given over to Saints’ Days -- religious celebrations which

were in fact excuses to glut out on food, alcohol and dance in

order to achieve the bliss of unselfconsciousness. In our time,

we only have to think of Mardi Gras, the Mexican Day of Dead,

The Rio Carnival and the all-night rave party to be reminded that

the burden of self-consciousness remains the same from one culture

to the next. It’s not for nothing that we turned Dionysus

into a God for all seasons and that his unacknowledged devotees

number in the billions.

So if

we don’t literally harbour a death wish that is supposed

to culminate in the act of suicide, we are profoundly and transparently

attracted to states of mindlessness that prefigure death, the

remarkable insight of which secures Freud his highest ranking

among the great geniuses of the 20th century.

YOUR COMMENTS