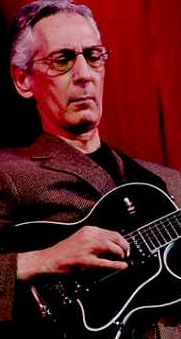

Featured artist: PAT MARTINO

Pat

Martino played to a full house for the 2006 version of the Montreal

Jazz Festival. R. J. DeLuke spoke

to Pat about his life and music.

___________________

Pat Martino, he of the quicksilver fingers, the intuitive genius,

the beauty of tone, is the type of artist that makes other guitarists

shake their heads. But there are other things at work in the magical

process. We’re not talking about whether the piano is in tune.

Not the sound of the drummer. Not the quality of a sideman’s solo.

The

guitar is an extension of his life, and appears to have always

been that. He loves the feel, sound, look and touch of the instrument.

“My favorite toy,” the 62-year-old calls it with the honesty of

a child.

“It’s

different for each of us. For me personally, nothing works other

than me. I work and I enjoy doing what I do because I always do

the best I possibly can. No matter what takes place, I know that

things are going to work out. My intention is to amplify self-esteem

in as many ways as I possibly can. Working is doing the best under

any circumstance.”

Hearing

him in a club is to know that. And hearing his latest CD, the

wonderful Remember: A Tribute to Wes Montgomery is to realize

the guitarist is special. An homage to one of his greatest influences,

the ten-cut disc is a treat from start to finish. He’s rightfully

proud of it. But it doesn’t define him. In this cluttered world

of intolerance and trouble and George Bush, his music shines through;

an oasis for the soul weary. Pat Martino—having come through life-threatening

illness; having come through a brain aneurysm so devastating that

in its aftermath he didn’t even remember he was one of the great

jazz guitarists; didn’t even remember friends and family— smiles

through both the art of the music, and the smothering dysfunction

of existence in the new millennium.

He remains

calm. He sees things differently. He copes. All that he has been

through has been his road to that point of being at peace.

“A good

example would be being at the airport, on my way out to one of

the spots on the tour, and being subject to security and standing

in a line that’s ferocious in terms of its demands upon patience

and endurance and tolerance,” he says with a knowing calm. “So

here, in terms of what I find myself in under those moments, when

I’m clear of mind and intention, I find myself amidst one of the

greatest studies of virtue there can be. And that is rewarding.

So I stand there and try to remain as neutral as I possibly can

and feel good about it. It’s a re-shaping of something that is

very fluid and takes the shape of whatever you pour it into. That’s

healthy. I like that.”

A conversation

with Martino makes the immediate impression that it is a discussion

with a deep thinker; a man who is living in the same reality,

but looking at it from a different angle, and comfortable in his

own skin.

“Music

has always been latent as a blessing of its own accord,” he says.

“It has been second nature to me as an ecstasy of its own nature.

When it comes to craftsmanship, with regard to being a musician—or

an electrician or an attorney, any of these crafts that are in

a social context; functional—I see these as one and the same.

As a responsibility to participate with values, in terms of interacting

socially with other human beings, other individuals.

“But

when it comes down to the intention of the individual that utilizes

that particular instrument, which is their craft, their intentions

determine their reasons for what they do, and in most cases transcend

the nature of the craft itself. It’s very much similar to: If

I were to be totally consumed by the process of musicianship itself,

I then would be subject to what most musicians are subject to:

a responsibility of practicing each and every day for a number

of hours. And I did, when I was younger, due to lack of experiences

in a deeper sense.

“I think

many of us see it that way. We see it different than a tool, a

communication tool. And we see it as a career that is subject

to competitive demand. We have to compete. To do so we have to

really constantly replenish our physical abilities. That’s what

practice is all about. On the other hand we have an automobile

that we drive. And we never practice putting the key in the ignition.

Nor do we practice the gas pedal or the brake or anything else

in that particular tool. We don’t even think about it until we

have a destination to use it for. That’s what guitar is to me,

similarly. Primarily because it’s second nature to me, just like

that automobile is. At some point down the line that, too, happened

to music itself… It brings me into the opportunity of interacting

with others, and some precious moments.”

And

on stage?

“It

all comes to fruition of its own accord, without prior intentions.

Sometimes it seems like intentions prior to now, prior to the

moment—in other words constructing something for the future, leads

toward disappointment in many cases.”

Martino

is a musician of the moment, a key element of jazz. The guitar

is the tool he used to communicate, and he remains fascinated

with it, just as he was as a child when he would sit down and

figure out how it worked. The same wide-eyed wonderment he must

have had when he moved from Philadelphia to Harlem at the age

of 15 to find out more about the music and join in the cooperative

of the people who were making the important sounds of the time—sounds

that are still the cornerstone of what is played today.

In fact,

conversation was politefully disrupted for a time in order for

the musician to answer his door. An obviously happy Martino returns.

“I was waiting for this guitar to come in from Gibson. That’s

what it was. FedEx. It’s very exciting. It’s like a little boy

with a new toy,” he says with a chuckle.

That

type of élan is refreshing. It just happens to be the spirit of

the music that can be heard on his Wes Montgomery tribute, a cooking

album of songs from the Wes songbook.

Martino

met the guitar legend when he was fourteen, introduced in a club

by his father, who sang in Philly nightclubs. “At that particular

age, I had not as of yet experienced participating as a professional

in the craft. I still remained within a dreamlike state of perception

when it came to the definitive meaning of people in general. Wes

Montgomery was the warmest person I had met until that time. So

I wasn’t really moved as a professional musician, in terms of

his artistic presence — although I was completely overwhelmed

by his dexterity. I was moved more than anything by the warmth

in this particular individual. And that opened up a completely

different motif in upcoming definitions of what was important

in life.”

He calls

the tribute “a very honest one” and music “a pool of respect for

a great artist. It was literally like a lake, where those particular

topics reside within. If you go swim in that lake, it’s gonna

really swing. Those tunes were hard core Wes Montgomery prior

to his marketing success.”

Some

feel that Montgomery left the realm of mainstream jazz for more

commercial music. Martino doesn’t see that as a bad thing in that

case. He feels Montgomery pulled off things like Beatles covers,

“wonderfully, I really do. I have preferences with regard to my

own tastes. I think to run the gamut is respectful in itself with

regard to how many ways his creative ingenuity provided success

at all times.”

No commercialism

here, however. The band—David Kikoski, piano; John Patitucci,

bass; Scott Allan Robinson, drums; Danny Sadownick, percussion—cooks

from beginning to end. The groove is happening at all times, whether

swinging like mad or on the two ballads.

“Yeah.

We were very excited about it. I think it had something to do

with respect, due to the fact that the motif was based upon authenticity.

That had a great deal to do with the effect it had on each of

us — to try to remain as concrete as possible with regard to reanimating

that particular segment of our culture.”

The

disc kicks in right from the start with “Four On Six” which highlights

the deep swing of the album. Not only is Martino nimble and hip,

but Kikoski is locked in, tearing it up. The pianist is one of

the heroes of the album, his playing superb throughout, light

and nimble, yet ballsy and groovin’. Like Martino. And the rhythm

sections digs and lays it out for the both the soloists and the

whole musical concept. “Twisted Blues” cooks. “West Coast Blues”

is like a ride along the Pacific highway. “If I Should Lose You”

gets a ballad treatment that is dirge like in tempo, but never

maudlin. Martino squeezes out notes that hang in the air and deliver

the heartfelt sentiment of the song without anything mawkish.

The whole thing is a gas.

Martino

says there will be some touring done in support of the disc this

year.

He says

the recording experience was profound, part of “ongoing re-ordering

of my lack of retainment-type of memory after the operations”

which, in turn, “demanded that I go back and evaluate and analyze

as much as possible what I do remember. One of the things that

has remained profound is the wishes and dreams of a child and

whether or not these have been brought to fruition.

“One

of the first things that I remember when it came to Wes Montgomery

was the addiction that took place as a child being exposed to

such art; such an individual and artist. I sat in front of my

father’s record player on the floor, overwhelmed with interest

in trying to reproduce what I heard coming from the speaker on

my favorite toy, which was the guitar. It still is my favorite

toy. So I sat there with my favorite toy and played with it, intensely

addicted to the process. That’s what this album brought me back

to. Something I wanted to do as a child was to be able to do what

I heard coming from the speakers.”

Martino

was able to travel back, as it were, to that childhood place.

“Which is something most individuals, I believe, rarely achieve.

To set out to go back to your childish dreams and to make them

come true of their own accord is a form of success that transcends

age. That’s what this album is all about. It’s achieving what

I set out to do when I was a little boy. And doing so with respect,

not only to its presence at that time, but its presence today

with no judgmental critique that in any way is comparative or

competitive.”

It’s

been a remarkable journey to that childhood place, and to this

place in 2006 with one of the sparkling recordings of the year.

It started in Philly where Pat was born in 1944. He was exposed

to jazz early through his father. He didn’t start playing the

guitar until the age of twelve, but it was clear that the instrument

was a natural fit to his hands and connected to something else

wired into Martino. “It was second nature,” he says. He left school

in the tenth grade to study music. His father wasn’t a direct

influence on the instrument. But in playing it, it was a way for

Pat to connect.

“I would

say that my intention was to move as close as I possibly could

to the individual position in our relationship that demanded respect

from him, based upon his own interests. The guitar was his greatest

interest when it came to the instruments. As a child, I was looking

for participation in respect with elders. That’s what I noticed

when I met Wes Montgomery and when I went to Harlem at the age

of fifteen and was, in a sense, guided and protected by my elders,

with respect to an innate talent. It has transcended music from

the very beginning.

“My

main concern since conscious childhood was to participate with

elders and to be adequate in terms of that participation—for them

to understand my opinion. In some ways it seems egotistic, and

I guess it is, to some degree. But it was essential for me to

do that.”

Martino

was largely self-taught, but did go for some training with a local

musician, Dennis Sandole. However, the guitarist doesn’t see it

as “training” as such. Again, in his unique view, it was something

different. A gaining of knowledge, but not in the traditional

sense.

“I had

the opportunity of being in the presence of older individuals,

generation-wise, and studying them, not what they were teaching,”

he says. “I studied their apparel. I studied their surroundings,

their environment.”

With

Sandole, “that’s where I met John Coltrane and Benny Golson and

Paul Chambers; quite a number of artists. I was supposedly to

be there to study what Dennis Sandole gave me as a weekly lesson.

And I found that absolutely impossible … I would study what he

wore and why there was a copy of a Van Gogh on the wall. And why

the guitar over in the corner had dust on it, and the piano was

clean. … I studied these things in depth, with regard to their

meaning and how that produced so much respect for this individual.

That’s what I studied.”

At the

age of 15, he was playing lounge gigs in Philly, sitting in where

he could, usually accompanied by his father. His first road gig

was with jazz organist Charles Earland, a high school friend.

“At that

time Charlie was a tenor player. We went to Atlantic City together

to a place called the Jockey Club,” Martino recalls. “Down the

stairway in the basement was a little club. In there was an organist,

Jimmy Smith. When we heard that, Charlie gave up the tenor saxophone

forevermore. He wanted to be an organist and that’s what he did.

We started getting together in the garage across the street from

his parents’ house. We practiced and put a little trio together.

Charlie could only play in C minor, god bless his soul. He would

have the left hand together, and he’d comp with the right hand

in C minor. I would have all the melodies to play across the C

minor blues.”

It was

this association with his old friend that was a step to bigger

things, especially when the trio booked a gig in Buffalo, NY.

“Recently I described this to someone and got a flashback and

remembered the name of it. The place was the Pine Grill. We went

there and played. One evening, in came an entourage of people

from one of the shows in town. That was Lloyd Price and his manager

and a lot of people from the big band. They sat at the bar and

listened. Lloyd Price called me over. I was 15 years old. And

he said, ‘Listen. If you ever want to play with a great big band,

here’s my number. Call me. I’m in New York City. You’ve got the

job if you would like to do it.’

Martino

followed up on the offer, with blessing from his father, who spoke

with Price. He wound up in Harlem with Willis Jackson and played

with both on and off for a number of years.

“It

just so happened that at that time in Lloyd Price’s 18-piece big

band, the arrangements were being done by Slide Hampton. And in

the band was Jimmy Health, the Turrentine brothers, Stanley and

Tommy, Red Holloway was in the band. Charlie Persip was the drummer.

Julian Priester was in the band. It was a band of all-star jazz

players. We would play for an hour or an hour and a half sometimes

— just the band with some really modern jazz arrangements, original

stuff. Then Lloyd would come out for one half-hour or 40 minutes

and do a show.

“Whenever

the band wasn’t working, everyone went in their own direction.

That’s where I would perform with Willis, or Jack McDuff, or Sonny

Stitt and Gene Ammons. It was a great time in our culture. Very

volatile.”

For

the young Martino, his age didn’t matter, nor did the rigors of

everyday life a teenager would have to encounter in the big city.

His elders looked after him. And he was where he wanted to be.

“I lived

in a dream and jazz was heaven. Jazz was Disneyland to me. I wanted

to meet these people. I wanted to meet Jimmy Heath. I wanted to

meet Jimmy Smith. I wanted to meet Wes Montgomery. I wanted to

meet Les Paul. A lot of people. All the people who, as a little

boy, I looked up to. The stars. The successful ones; the dreams

come true.”

His

reputation among jazz giants grew and he could count among friends

the likes of Les Paul and George Benson. The youngster was in

the middle of a burning jazz scene and he had many influences

on guitar.

“The

first was Les Paul. The second was Johnny Smith. The third was

Wes Montgomery. In between Johnny Smith and Wes Montgomery were

influences that were not as profound as the three that I mentioned,

but just as powerful in their own way,” he says. “One of those

was Hank Garland. Another was Howard Roberts. Another was Joe

Pass. These six players on the guitar were major influences to

me. … Aside from the guitar, my main influences were Donald Byrd

and Gigi Gryce. Gerald Wilson with the big band. More than any

of the influences mentioned, the greatest influence to me was

John Coltrane. There were many things.”

The

gigs were steady, the Big Apple generally welcoming and Martino

was among the finest of his craft. He played with the likes of

Sonny Stitt. A gig with John Handy took him to California, where

he also started doing some teaching. He was signed by Prestige

and recorded a string of albums including El Hombre (Prestige,

1967) and East! (Prestige, 1968). But in 1976, at the age

of 32, the headaches started. Severely. And there were blackouts.

“It brought

things to a halt by 1977. At least in terms of performance. Then

I moved to California, to Los Angeles, and took a position as

part of a faculty,” says Martino. But troubles continued. He was

misdiagnosed as manic depression, even schizophrenic. Wrong medications.

Electric shock treatments. Confinement in a psychiatric ward and

close to suicide. There were periods when he could function, but

continued problems landed him in the hospital. The brain aneurysm

was discovered.

Operations

in a Philadelphia hospital left the artist in a coma. The brilliance

of his creative energy, it appeared, was at an end. His very life

hung in the balance. But Martino did not succumb. He awoke. He

lived. He was discharged.

But

he did not recognize a soul. Not his parents. Not his friends.

He didn’t know he was a guitarist, much less one of stature. Martino

went to his parents home to recover, but amnesia made the process

painful. His father showed him copies of his albums. Showed him

the instruments. Friends like Les Paul called. While memory slowly

came back, Martino’s desire to play did not. In fact, if anything,

he was repelled, feeling that he was being pushed into something

in which he had no interest. Dark times continued.

“That

was very painful. It produced a very painful situation for me,

because I was recovering at Mom and Dad’s house. Because of this,

I was subject to and had to endure listening to my old records

come through the floor when I was upstairs in my own little bedroom

in isolation. I heard my father playing my records. I didn’t want

to hear that. I didn’t like it. I saw the albums and I saw the

guitars and I saw a responsibility of something everybody wanted

me to do. And I didn’t feel that I had to do that, to please them.

I had a lot pain going on and I didn’t want to please anyone.

I wanted to overcome the pain and hopefully at some point enjoy

being alive. So that’s what it meant, my albums and my career

and all of that. I didn’t really want to get into it.”

It wasn’t

anyone’s prodding that brought Martino back to music. He went

back on his own. Maybe music met him half way.

“Finally

it got so painful,” he says simply, “that I went into the guitar

itself. It was the only thing that started to become enjoyable.

It turned into an ecstasy once again.”

“In

its profundity,” Martino explains matter-of-factly, “it produced

the very thing that caused me to play to begin with. That was

to get away from all the things that I was supposedly responsible

to do. That’s what children are interrupted with.

“You

have a child who is totally in ecstasy; playful, creatively objective

at all times; even subject to creativity. Along comes the parent,

with loveable responsibility, and says to the child, ‘Stop playing

and do your homework.’ That to me was an interruption in the ecstasy

itself, and I think it is for each and every individual in the

growing process. Those who adjust to the oncoming responsibilities

to participate in a social architectural framework, and be utilized

for purpose that is separate from the individual. These take their

place within that household, in that factory, in that industry,

in that society, within that culture.

“What

took place when I forgot everything was the beginning, once again.

It was the black border erased. It brought me to where I was in

the very beginning. The only difference was, due to the compassion

and the concern of so many others around me during that recovery

period, it became clear I was in bad shape. I didn’t realize whether

I was or I wasn’t. But everybody seemed to think that I was. This

produced pain. That’s why I had to recover and that’s what I had

to recover from. Procrastination on my behalf caused the pain

to amplify beyond belief. That caused me to run toward the one

thing that I ran to before when I was a child: my favorite toy.

I lost myself in that. I procrastinated on a decision to be career

oriented with that toy again, for the second time. Until I saw

there was no difference in playfulness, whether it be publicly,

or privately, isolated. It made no difference the second time

through. Primarily because I was not participating. I was not

entering back into it with a competitive intention. My intentions

were totally self-rewarding.”

It wasn’t

easy. There were still medications and therapy and problems with

pent up anger, he says. Martino did not have to study the guitar,

did nothing academically. Part of his therapy was using a computer

graphics program. And the music returned. The dexterity returned.

The creativity returned. In the late 80s, he was back performing,

including the aptly named album The Return (Muse, 1987).

But there were some setbacks, including the death of his parents

months apart in 1989 and 1990. Still, music prevailed. Martino

prevailed. With pianist Jim Ridl he recorded again, producing

works like The Maker (Evidence, 1994). He was back, musically.

But poor

health of another kind appeared. He got severe pneumonia, chronic

bronchitis and emphysema and lost a tremendous amount of weight.

Doctors felt a lung transplant was in order, but his wife, Ayako,

who he met in Tokyo in the late '90s, refused and took him under

her wing. Alternative methods of care that included an organic,

all-vegetable diet, and yoga. He says he went from about 86 pounds

back up to 165 in about five weeks.

In 2000

he was touring again, and recording for Blue Note records, who

had signed him a few years earlier. “Yeah. Back to recording,

back to social interaction and the enjoyment of old friends, artists

in many different fields who were inspirational and stimulating.

That’s where it sits today.”

The

rest has been a succession of good records, outstanding performances,

and carrying on life as a creative artist. His latest recording

is a testament not only to Wes Montgomery, but also to how far

Martino has come, and to the strength of his artistry.

Martino

doesn’t really concentrate on future projects, preferring to take

life as it comes.

“I’ve

always found it difficult to describe something that does not

exist, primarily because in doing so, there is a lack of a concrete

result,” he says. “There are things I would love to do. I would

love to do something with strings. Whether or not this can come

about budget-wise is another story.

“So

I have no idea what’s coming next. It comes of its own accord.

It comes as part of the growing process. So I let it rest and

be what it wants to be when it wants to appear.”

Bravo.

Selected

Discography

Pat Martino, Remember:

A Tribute to Wes Montgomery (Blue Note, 2006)

Pat Martino, Think

Tank (Blue Note, 2003)

Pat Martino, First

Light (Starbright, 1976 and Joyous Lake,

1977 on one CD) (Savoy Jazz, 2003)

Joey DeFranceso, Ballads and Blues (Concord, 2002)

Pat Martino, Live

at Yoshi's (Blue Note, 2001)

Philadelphia Experiment, Philadelphia

Experiment (Atlantic, 2001)

Pat Martino, The Maker (Muse, 1994)

Royce Campbell, Six

by Six: A Jazz Guitar Celebration (Moon Cycle, 1994)

Pat Martino, The Return (Muse, 1987)

Pat Martino, We'll Be Together Again (Savoy Jazz, 1976)

Pat Martino, Exit (Muse, 1976)

Pat Martino, Consciousness (Muse, 1974)

Pat Martino, Live! (Muse, 1972)

Pat Martino, Footprints

(Muse, 1972)

Pat Martino, Desperado (Prestige, 1970)

Eric Kloss, In the Land of Giants (Prestige, 1969)

Pat Martino, Bayina (The Clear Evidence) (Prestige, 1968)

Pat Martino, East! (Prestige, 1968)

Charles McPherson, From This Moment On (Prestige, 1968)

Pat Martino, El Hombre (Prestige, 1967)

Pat Martino, Strings! (Prestige, 1967)

John Handy, New View (Prestige, 1967)

Richard “Groove” Holmes, Blues Groove (Prestige, 1966)

Willis “Gator” Jackson, Soul Nite Live! (Prestige, 1964)

R. J. DeLuke is a regular contributor

at All

About Jazz.